Note: The following is the first installment in a series of guest blog posts that complement Charles Steffen’s recently published article “The Rise and Fall of Atlanta’s Skid Row” by highlighting the continuing pertinence of those issues in Atlanta today.

Darin Givens is well-known for his blog ATLurbanist and more recently as the co-founder of the urban advocacy group ThreadATL.

Last year I was walking with my 9-year-old son through South Downtown Atlanta. I’ve always enjoyed getting a close-up look at the old buildings that remain there from the district’s heyday as a major shopping destination, and walking the great old street grid from the city’s earliest years.

But the charm was lost on my son. He told me that he didn’t like the place because it was scary and “looked like a prison,” which I assume was a reference to the bars on some windows and to the general bleakness of much of the landscape thanks to several empty structures and many parking lots. The fortress-like government offices were not helping matters.

His reaction to the aesthetics of the neighborhood was superficial, but understandable. The negative impact of the ugly parking facilities and abandoned buildings can make it hard to notice the positive aspects of the area.

I had wanted to walk around the neighborhood that day because, at the time, I was serving on the board of Eyedrum art gallery and I was assessing what the experience of South Downtown was like for visitors to our programs. As the only Downtowner on the board, I was particularly concerned about how visitors would perceive the sometimes-bleak surroundings. Assessments of South Downtown that focus only on the surface level can end up missing the many great things that are happening inside some of the remaining old buildings, such as the many arts organizations that have established homes inside them over the past four years.

Attachment and detachment in South Downtown redevelopment

One of the best things to have happened to the South Downtown neighborhood in the past few years is the presence of arts groups that have either relocated here or emerged fresh as new faces on the scene. Eyedrum, Mammal, Murmur, Downtown Players Club, C4 Arts Center, and more have all made commitments here – engaging in the considerable work needed to get old buildings in shape and to bring visitors into a challenging environment for nighttime events. The time and resources that these organizations have invested in making a home in South Downtown has given their leaders an attachment to the place and a desire to see it succeed.

But will they be able to see the success when it comes? A developer, WRS, has purchased several old commercial buildings with intent to renovate them. There’s a very real fear that some of the arts organizations currently housed in them (along with long-time retailers) could be displaced. If this happens, the very people who’ve worked so hard for success in the neighborhood may not be able to remain when new investment arrives.

What we lost

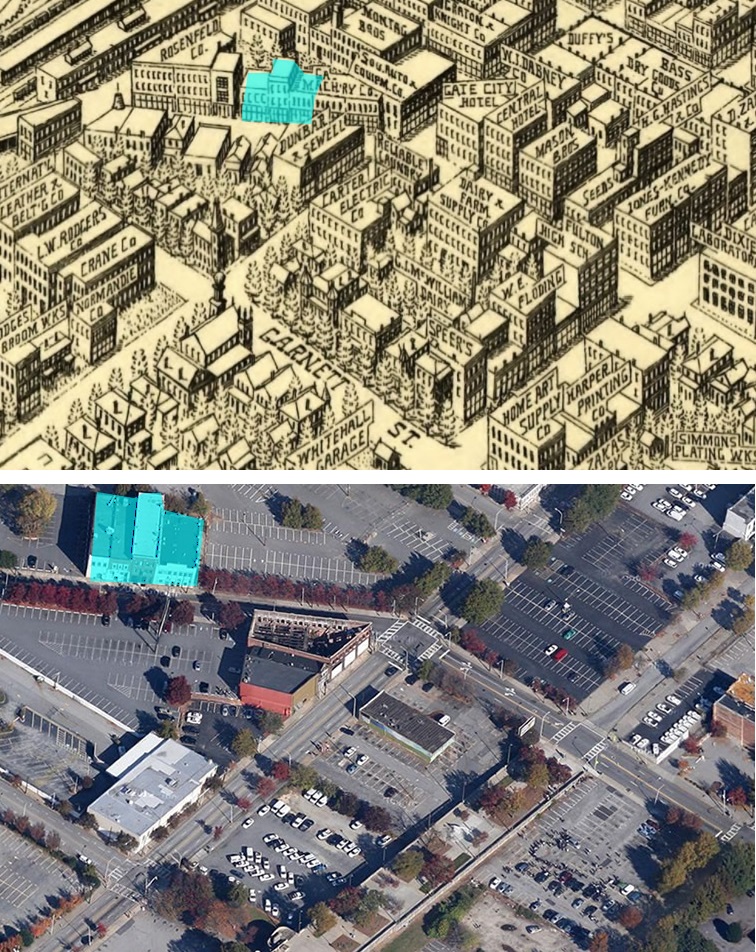

These art organizations have taken up residence on streets that contain elements of the sort of urban blight that may be familiar to anyone who’s visited downtowns of mid-sized cities around the nation. Many US cities experienced crippling disinvestment during the mid-twentieth-century era of white flight and suburban sprawl. In Atlanta, South Downtown is the place where that era left its cruelest mark on the built environment. Here are a couple of images to illustrate:

The top image is taken from a 1919 aerial map of Atlanta’s South Downtown, at the intersection of Trinity Avenue and Forsyth Street. It’s typical of the compact land use of pre-automobile cities. The bottom photo shows what we have in that spot today. I shaded in blue the only set of structures left intact after the surroundings were converted to parking lots.

Three MARTA rail stations serve the area – a fact that makes the underuse of these properties particularly frustrating, while also helping to explain the lack of buildings in this section of South Downtown. Many of these lots were rezoned for maximum building height during MARTA construction, in the hopes that skyscrapers would pop up. They never did, and because of those allowed heights, property owners are unwilling to greenlight more modest development.

On the website for my urbanism advocacy group, Thread ATL, I recently posted about a startling proposal by the city to build even more parking here, for use by government staff, despite studies which show that the district is significantly “overparked” already and despite the presence of transit lines. This proposal raises the question: do city leaders recognize that properties dominated by parking facilities are undermining – through both the unpleasant dead spaces they create in the urban fabric and the car traffic that they induce – the historical importance and future potential of South Downtown?

Bottom Image: Courtesy Google Maps.

What We’ve Gained

Challenges posed by the disused parcels linger, but they are being met by the way the arts community and others have treated this district in increasing numbers through redevelopment and community engagement.

This year’s Elevate program – an annual arts event from the city’s cultural affairs office – included a dinner on Broad Street in South Downtown. The guests included members of advocacy groups, arts organizations, retail owners, city council members and staffers, neighborhood residents, and more. Deep into the night, the event inspired lively conversations about the kinds of things that would improve the area for the benefit of the city at large without doing harm to the good things that have been happening. Bit by bit, these discussions are lending shape to a new understanding about what future of this space can look like.

In addition to such conversations, visions of the future – but not necessarily ones all share – are being spurred by signs of investment in vacant properties in South Downtown. One commercial building is slated to become new apartments and another one a hotel – both of these will be making use of spaces that are currently empty.

These investments in empty and struggling properties might be encouraging, but all of them could be swallowed up by the persistence of negative-impact space. The neighborhood’s parking lots and abandoned buildings still linger. For movement on those, the city will have to encourage adaptive reuse of old structures and, perhaps most importantly, address those height limits, which are stifling the need for incremental growth over those parking lots.

An intentional effort to make South Downtown look less “like a prison” through the deadness of parts of its urban fabric is needed. And that effort will be just as important for the goal of creating a vibrant neighborhood as filling in the blanks of empty old buildings. Moreover, prioritizing South Downtown revitalization makes sense. This is a place that is filled with the history of the city’s origins and that sits in a central location between neighborhoods that vary greatly in demographics and culture. It has the potential to connect us to our past, present and future, and to each other. But in order for it to do so, we need for the neighborhood and its buildings to not just be viable for developers – Atlanta and its residents need it to be lovable.

Citation: Givens, Darin. “Conflicting perceptions of South Downtown’s potential.” Atlanta Studies. December 08, 2016. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20161208.