With these words, on November 30, 2005, the newly elected mayor Eva Galambos congratulated the residents of Sandy Springs, a largely white and affluent suburb located about fifteen miles north of Atlanta, on their success in incorporating as an autonomous municipality:

The eyes of metro Atlanta, of Georgia, and indeed, the nation, are on us as we begin our wonderful civic adventure of self-government. 1

Since the mid-1970s, a group of Sandy Springs activists had been engaged in struggle against Atlanta and Fulton County to obtain local government to end what they perceived as the burden of financing welfare and public services in the low-income, majority–African American areas of South Fulton 2 The successful incorporation also marked the beginning of a bold neoliberal experiment in local government, making Sandy Springs the first large US city to outsource the majority of its services first to a single private company, and then to multiple private contractors. 3

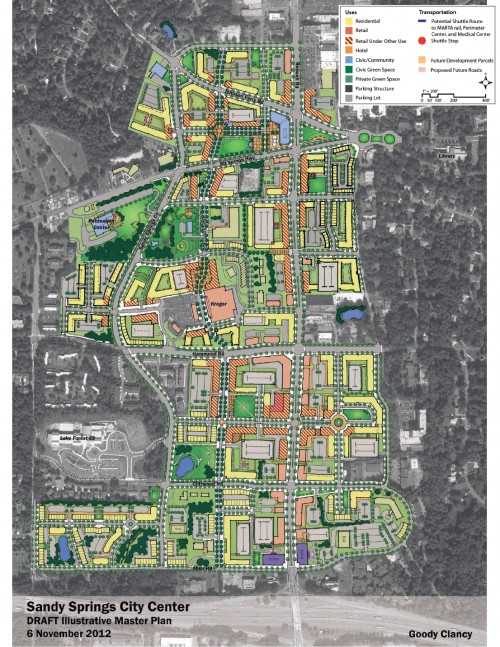

In 2012, the Sandy Springs City Council approved a multi-phase plan to transform the sprawling and quintessentially suburban landscape of Roswell Road into a “city center” exhibiting the newly acquired municipal identity and fostering “community pride.” 4 Drawing on ethnographic research, this article analyzes perceptions, representations, and debates surrounding the City Center Master Plan. I examine two divergent interpretations of the plan that circulate in Sandy Springs’ media, everyday conversations, and institutional discourse, investigating their connections with the “color-blind” language employed during the struggle for municipal incorporation. I argue that the place-making and civic-branding project of downtown redevelopment may function as a growth-seeking strategy that marginalizes low-income residents of color by inscribing an exclusive, sanitized, and commodified definition of “community” and “diversity” onto the landscape.

Developing City Springs

Between 2005 and 2012, Mayor Galambos and her collaborators took the first steps towards the construction of a new downtown. First, they began to add sidewalks, streetlights, and pedestrian crossings along Sandy Springs’ major thoroughfares. Then, they acquired a fifteen-acre vacant commercial property situated in close proximity to Roswell Road and to the local heritage site, 5 envisioning it as “the ideal platform for a new city center.” 6 In December 2012, at the end of a series of public meetings, municipal leaders finally approved the Master Plan, subsequently outsourcing the implementation of its first phase – scheduled to be completed by December 2017 – to two real estate developer firms.

Officially named “City Springs” during a “branding” ceremony in the summer of 2015, 7 the project aims to create a “unique, vibrant, walkable city center rich in amenities desired by the community,” such as high-end retail stores and restaurants, a central park, luxury apartments, a new City Hall, and a performing arts center. 8 By committing $230 million in bonds and tax revenues to the realization of this “transformational public-private development,” 9 the city hopes to “catalyze significant market-driven private investment” 10 along the Roswell Road corridor, turning the area into a desirable destination for middle class consumers, young professionals, and business and cultural entrepreneurs. At the same time, City Springs will also serve to “build a connective tissue” among different neighborhoods, providing residents with a “place to be a community” and to “care about each other.” 11Interestingly, this portrayal of the future downtown as an inclusive place of community building is often framed in a language of “diversity,” with particular reference to the demographic shifts that the city has recently undergone. In line with regional and metropolitan migration trends that have brought new diversity to area suburbs, over the past two decades Sandy Springs has seen a gradual increase in African American, Latino, and other immigrant residents, together now constituting about 41 percent of the total population. 12

This section of the population is predominantly low-income, employed in low-wage construction and service sector jobs, and concentrated in the apartment complexes along Roswell Road. 13 As these populations became increasingly visible in the areas targeted for redevelopment, discourses emphasizing “diversity” also began to take on ambiguous and increasingly contested meanings.

Here is how Mayor Rusty Paul, for instance, explained why initiatives such as open-air concerts and movies held at the Sandy Springs’ “heritage” park constitute a successful model for the kind of interaction that the future civic center should foster:

You are looking at people sitting there, and it’s white, it’s black, it’s Latino, it’s the entire rainbow of American color . . . on that hillside, sitting there together being community. 14

Later in the conversation, however, he added:

. . . when I talk about diversity in a community like ours . . . we’ve got ethnic diversity, and we have economic diversity. But now we have to create that generational diversity that makes for a healthy community. 15

To achieve this last goal, the municipality has to build “a mix of middle income and empty-nesters housing” targeted to baby-boomers looking to downsize as well as “millennials” working in the nearby Perimeter district.

According to the Master Plan, “provid[ing] opportunities for a broader array of residents and families to join the diverse downtown community” is key to improving quality of life and raising property values in Sandy Springs. 16 Although public officials have repeatedly assured the citizenry that a percentage of the new housing stock will be accessible to nurses, schoolteachers, police officers, and other workforce who currently cannot bear the cost of living in the area, 17 when asked about affordable housing, Mayor Paul responded: “well, there is a lot of nervousness about that . . . but that’s not an issue today. In fact, we have an overabundance of low-income housing in this city.” 18 His words echo recent municipal discussions and ensuing decisions targeting the “aging” and “deteriorated” apartments along Roswell Road. 19 Starting from 2014, in fact, the administration has approved a series of zoning changes to lure developers into the Roswell Road corridor, encouraging them to acquire and demolish old residential and commercial properties, and replace them with “high quality” 20 mixed-use developments. 21

Diversity and Displacement

As municipal decisions resulted in the demolition of three large apartment complexes, with many more scheduled to come, some residents began to voice concerns that the plan to “diversify” Roswell Road could actually be an ill-disguised attempt to de-concentrate poverty by drastically reducing affordable housing options. Some of the public comments collected during a recent campaign leading to the drafting of a new comprehensive land use plan, for instance, urged administrators to “keep in mind the reality of displacement of working class families, who get priced out.” 22 Responding to the official plan’s insistence on owner-occupied rather than rental units, another person wrote: “unless new ‘home ownership’ options are going to be truly affordable, don’t take any of our apartments.” 23Similar concerns emerged from interviews with low-income families and the community activists helping them. Eric Silva, for example, works for a nonprofit organization that offers financial and educational support to low-income youth. Due to the recent re-zonings and demolitions, Eric told me during one of our conversations, many Latino families were forced to relocate elsewhere in Sandy Springs or to other suburbs, facing issues such as school overcrowding, lack of public transportation, and loss of formal and informal networks of support. 24 It is perhaps not surprising, then, that several apartment residents saw redevelopment and rent increases as part of the “mayor’s ten year plan” – that is, as deliberate attempts to “clean up” neighborhoods by “kicking out” minority residents. 25 Finally, Gabriela Mendoza – who works for a community-based organization providing financial help and social services to needy residents – bluntly noted that low-wage laborers are essential to support Sandy Springs’ thriving service economy. And yet municipal housing policies seem to disregard this crucial aspect of “community” building:

The low-income housing is disappearing. Dramatically … The city would be very wise to do mixed-income housing, there are a lot of us who are pushing in that direction. I think what the politically conservative people that want the low-income people out of here don’t realize is that, if you don’t have housing for all of the different income levels, you don’t have buy-in from them, and therefore you don’t have the dedication to be part of the city.

While similarly regarding gentrification and displacement of the poor as intended consequences of the downtown plan, residents sometimes traced a direct connection between the rationale guiding those decisions and the reasons behind Sandy Springs’ struggle for incorporation. When a newspaper published an online article about the apartment demolitions approved in 2013, sentences such as this one appeared in the comment section:

The truth is this is about pricing out the poor and non-whites. It’s also about making money for the developers. Sandy Springs incorporated for two reasons and those were money and legally removing the poor so that the delicate eyes of the well-off don’t have to see them.26

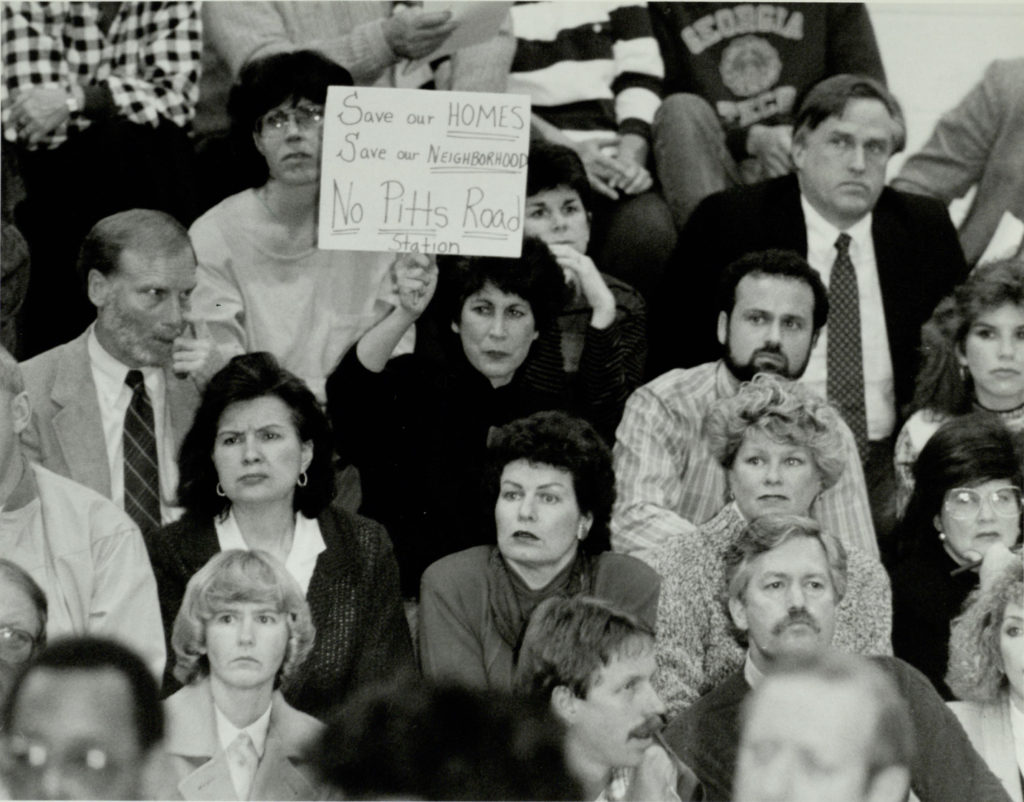

Laura Greene, a young activist working in a local church, similarly referred to the decades between the 1960s and the 1990s, when the local population was almost entirely white, observing: “I think they want to bring things back to how they were.” But how exactly were “things?”

From “Color-blind” Histories to “Color-blind” Spaces

Sandy Springs’ first push for incorporation originated in a postwar context characterized by uncontrolled suburban growth and government-sponsored white flight. Formed by Eva Galambos in 1974, the “Committee for Sandy Springs” was initially focused on preventing further annexation attempts from Atlanta and advocating for local government. The latter would have enabled residents to control the process of racial de-segregation of schools, parks, and neighborhoods, while also giving them the right to “spend tax money locally,” 27 and to protect their neighborhoods from the encroachment of apartment complexes and commercial properties. Over the years, the committee gradually abandoned the anti–civil rights, overtly racist rhetoric that they had originally used against annexation, drawing instead on rightist, anti-welfare, anti-urban, and “colorblind” political discourses stressing the virtues of a privatized local government protecting homeowner and taxpayer rights. 28

Ethnographic research suggests that this “colorblind” narrative is currently being re-appropriated and transformed to deal with a context where low-income minorities are now living inside, rather than outside municipal boundaries, occupying the streets, parks, and sidewalks that are envisioned to become Sandy Springs’ future “heartbeat.” 29 In the early 2000s, the growing presence of minority populations in the area became a useful symbolic resource for committee activists eager to deny the significance of race as a component of municipal incorporation. 30 Today, the administration is in turn emphasizing “diversity” and inclusivity as assets to investors and potential gentrifiers to low-income residential areas. 31

At the same time, these narratives tap into and are reinforced by the metaphors of blight, crime, and aesthetic degradation that middle class residents and community leaders use to portray apartments as in need of redevelopment, while carefully avoiding any explicit reference to the racial and/or ethnic background of their residents. During interviews, everyday conversations, and social media posts, participants repeatedly used words such as “slums,” “filthy,” “blighted,” “run-down,” “terrible,” “dangerous,” and “crime-ridden” to describe the apartment complexes. Direct references to their tenants, albeit less frequent, included labels such as “Mexicans,” “illegal aliens,” “bad apples,” and “neighbors who will steal your things.” Apartment residents were also depicted as “a heavy transient community that is not invested in how the City of Sandy Springs operates” 32 and whose presence affects the quality of local public schools. All these racially coded utterances stigmatize non-white social groups indirectly, by discursively constructing the social and built environments where they reside as dangerous, dirty, disorderly, pathological, and morally flawed. As other scholars have showed, such representations are often deployed to justify projects of neighborhood revitalization that will render an area “‘safe’ for investment by remaking a black [and brown] space white.” 33

Conclusion: everybody’s neighborhood?

The contradictions that lie at the heart of the project of downtown redevelopment push us to interrogate Sandy Springs’ deeper history of racial and social exclusion through place- and city-making. Official discourses portray the future city center as “everybody’s neighborhood” – an economically, racially, ethnically, and generationally “diverse” environment that will foster meaningful interaction across different population groups. Some residents, however, have been questioning the plan’s real goals and the “code words” 34 used to promote it, stressing the social costs that the low-income population will have to bear. If implemented according to these premises, the City Springs project may ultimately result in the consolidation of an exclusive, sanitized, and commodified definition of “community” and “diversity” appealing to potential investors, middle class residents, and consumers. The “color-blind” discursive strategies that Sandy Springs activists and residents previously used to advocate for municipal autonomy, in turn, may become crucial to portraying the spatial marginalization of poor minorities as the “natural” and “racially innocent” 35 consequence of free market self-government.

Citation: Lanari, Elisa. “Excluded from ‘Everybody’s Neighborhood’? Constructing Sandy Springs’ New City Center.” Atlanta Studies. February 09, 2017. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20170209.

Elisa Lanari is a PhD candidate in cultural anthropology at Northwestern University. For over five years, she has been conducting ethnographic and archival research in suburban Atlanta, focusing on issues of social and spatial justice, neighborhood change, city-making, and suburban governance.

Notes

- Eva C. Galambos, “The City of Sandy Springs Inaugural Address,” November 30, 2005[↩]

- Before acquiring the status of autonomous municipality, Sandy Springs was an unincorporated area of Fulton County. For more details on Fulton County’s uneven racial and political-economic landscape, see: David L. Sjoquist, ed. The Atlanta Paradox. (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2000); Larry Keating, Atlanta. Race, Class, and Urban Expansion. (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001). For a comprehensive analysis of Sandy Springs’ thirty-year long struggle for incorporation, see: Michan Andrew Connor, “Metropolitan Secession and the Space of Color-blind Racism in Atlanta,” Journal of Urban Affairs 37, no. 4 (2015): 436–61[↩]

- For more information on the private-public partnership model, see: Oliver Porter, Creating the City of Sandy Springs. The 21st Century Paradigm: Private Industry. (Bloomington, IN: Authorhouse, 2006); and Oliver Porter, “Private-public Partnerships for Local Governments: The Sandy Springs Model.” Reason Foundation, January 29, 2010, http://reason.org/news/show/public-private-partnerships-fo-1. The city’s initial partnership with the Colorado-based global consulting firm Ch2M Hill was terminated in 2011, when Sandy Springs decided to split the contract for the provision of municipal services among many competitive bidders: see: Adrianne Murchison, “Sandy Springs Awards New Contracts; Leaves Out CH2M Hill,” Sandy Springs Patch, May 19, 2011, http://patch.com/georgia/sandysprings/city-awards-new-contracts-leaves-out-ch2m-hill.[↩]

- Rusty Paul, interview with author, September 2014. The material presented in this article has been collected during fifteen cumulative months of ethnographic fieldwork conducted between 2010 and 2016. Methodologies included participant observation, informal and semi-structured interviews, archival research, and analysis of media and institutional documents.[↩]

- For the acquisition and future redevelopment of this property, see: Dan Whisenhunt, “Buh-bye: Sandy Springs Target Demolition Planned,” Reporter Newspapers, December 11, 2013, http://www.reporternewspapers.net/2013/12/11/buh-bye-sandy-springs-target-demolition-planned/.[↩]

- The quote is taken from the official website of the project: http://www.sandyspringsga.gov/.[↩]

- “City of Sandy Springs Unveils New Branding for its Downtown Redevelopment Project,” Sandy Springs, GA: Latest City News, September 20, 2015, http://www.sandyspringsga.gov/Home/Components/News/News/186/52[↩]

- Goody Clancy, “Sandy Springs: City Center Master Plan” (2012), v, http://sandyspringscitycenter.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/2012-12-18_Sandy_Springs_City_Center_Master_Plan-Adopted.pdf.[↩]

- The quote is taken from the website of the real estate development company Carter USA, see: “City Springs: Sandy Springs, GA,” Carter USA, http://www.carterusa.com/projects/city-springs, accessed November, 29, 2016.[↩]

- Goody Clancy, “Sandy Springs,” v.[↩]

- Rusty Paul, interview with author, September 2014.[↩]

- Out of a total population of 94,000 people, today 20 percent of Sandy Springs’ residents identify as African American, 14.2 percent as Latino, 5 percent as Asian, and 2.7 percent with two or more races (US Census 2010). For the trends of suburbanization of poverty and migration in Atlanta, see: Audrey Singer, The Rise of New Immigrant Gateways. (Washington, DC: Brooking Institutions, 2004), http://www.brookings.edu/research/reports/2004/02/demographics-singer; Mary Odem, “Unsettled in the Suburbs: Latino Immigration and Ethnic Diversity in Metro Atlanta,” in Twenty-First Century Gateways: Immigrant Incorporation in Suburban America, Audrey Singer, Susan Hardwick, and Caroline Brettel, eds. Pp: 105–36 (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2008); and Alan Berube, “A View from Atlanta, Epicenter of Suburban Poverty in America,” Confronting Suburban Poverty in America, October 8, 2013, http://confrontingsuburbanpoverty.org/2013/10/a-view-from-atlanta-epicenter-of-suburban-poverty-in-america/.[↩]

- Connor, “Metropolitan Secession,” 448[↩]

- Rusty Paul, interview with author, September 2014[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- Goody Clancy, “Sandy Springs,” 21.[↩]

- Dan Whisenhunt, “We swear: Sandy Springs Begins New Era,” Reporter Newspapers, January 8, 2014, http://www.reporternewspapers.net/2014/01/08/swear-sandy-springs-begins-new-era/; John Ruch, “Sandy Springs Weighs Housing Police, Firefighters in City-Bought Homes,” Reporter Newspapers, August 2, 2016, http://www.reporternewspapers.net/2016/08/02/sandy-springs-weighs-housing-police-firefighters-city-bought-homes/; Tasnim Shamma, “Sandy Springs Housing Too Expensive For Mercedes-Benz Workers,” WABE, April 13, 2015, http://news.wabe.org/post/sandy-springs-housing-too-expensive-mercedes-benz-workers.[↩]

- Rusty Paul, interview with author, September 2014.[↩]

- Notes from Sandy Springs City Council Meeting, September 16, 2014.[↩]

- Rick Badie, comp. “Sandy Springs Gateway Project,” Atlanta Forward, July 31, 2013 https://web.archive.org/web/20130828170745/http://blogs.ajc.com/atlanta-forward/2013/07/31/sandy-springs-gateway-project/.[↩]

- For a comprehensive overview of the zoning changes and redevelopment priorities recently approved and/or currently being discussed, see the new comprehensive land use plan draft and related documents, The Next 10, http://thenext10.org/comprehensive-plan/, accessed January 29, 2017.[↩]

- City of Sandy Springs, “Sandy Springs Comprehensive Plan: Responses to Comments on Comprehensive Plan,” The Next Ten, https://drive.google.com/file/d/0BxHm-objQ-FKdzYxb2ZfbHNUbjg/view, accessed January 29, 2017.[↩]

- City of Sandy Springs, “Materials from the January 27, 2016 Community Workshop,” The Next Ten, http://thenext10.org/meeting-materials/, accessed January 29, 2017.[↩]

- The author used pseudonyms to protect participants’ identities.[↩]

- Interviews, March-April 2016. The “ten year” plan is most likely a reference to the Next Ten campaign to draft a new comprehensive land use plan discussed above.[↩]

- Badie, “Sandy Springs Gateway Project,” Atlanta Forward, July 31, 2013[↩]

- Eva Galambos, interview with author, January 2010.[↩]

- For a more detailed analysis of the transformation of the Committee’s rhetoric throughout the years, see Kevin Kruse, White Flight. Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005), 258; Matthew Lassiter, The Silent Majority. Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2006), 112; Connor, “Metropolitan Secession.” For a more general take on “colorblind” racial ideologies and discourses, see for example: Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, Racism without Racists: Color-Blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America, Third Edition. (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2009).[↩]

- Rusty Paul, interview with author, September 2014.[↩]

- Connor, “Metropolitan Secession,” 448–49.[↩]

- David Segal, “Georgia Town Takes the People’s Business Private,” New York Times, June 23, 2012, http://www.nytimes.com/2012/06/24/business/a-georgia-town-takes-the-peoples-business-private.html; Rusty Paul, “2014 State of the City,” The Springs-Times, Sandy Springs Newsletter, Spring 2014, 1–2.[↩]

- Adrianne Murchison, “Roswell Road Neighbors Hope to Control Density of Looming Mixed-Use Development,” Sandy Springs Patch, July 16, 2013. http://patch.com/georgia/sandysprings/roswell-road-neighbors-hope-to-control-density-of-loo10a15fbe6f.[↩]

- Deirdre Pfeiffer, “Displacement Through Discourse: Implementing and Contesting Public Housing Redevelopment” in Urban Anthropology and Studies of Cultural Systems and World Economic Development 35, no. 1 (2006): 72. See also Gabriella Gahlia Modan, Turf Wars: Discourse, Diversity, and the Politics of Place. (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008); Katherine Hankins with Robert Cochran and Kate Driscoll Derickson, “Making Space, Making Race: Reconstituting White Privilege in Buckhead, Atlanta,” Social & Cultural Geography 13, no. 4 (2012): 379–97.[↩]

- Robert Greene, interview with author, September 2013.[↩]

- I borrow the expression “racial innocence” to describe Sandy Springs’ past and present political strategies from Connor, “Metropolitan Secession.”[↩]