Sam Rosen, in a recent essay in The Atlantic, tackles Metro Atlanta’s “controversial” cityhood movement.

In the piece, Rosen gives a compelling overview of some of the major themes and histories that inform cityhood, touching on white flight, tax revolts, and racial politics, as well as governance, corruption, and self-determination. It’s a solid foray into a complex, ongoing phenomenon and its key players.

Where Rosen misses, it seems largely due to a lack of everyday familiarity with the Atlanta area (he refers to the failed City of LaVista Hills as a “neighborhood” when LaVista Hills doesn’t exist, and never has), a focus on the stories of people, and a preoccupation with intent, rather than a focused, analytical incision into the corpus of cityhood.

These incompletions and artifacts of journalistic writing do not necessarily constitute faults in Rosen’s well-researched and timely piece. However, these issues do open up a productive space for conversation and complication of the ways in which we think about, write about, and do politics around cityhood. For instance: what do we make of the reticence to engage substantially with legacies of racism in debates around cityhood? What does it mean for a black community to take up a tool historically developed and employed to the detriment of black and underresourced communities? Below, I tease out these and related themes in the context of the City of Stonecrest, and argue for a new politics of cityhood particularly attuned to history and geography in Atlanta.

The Anti-Politics of Cityhood

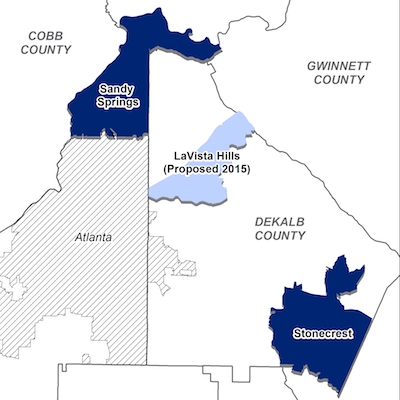

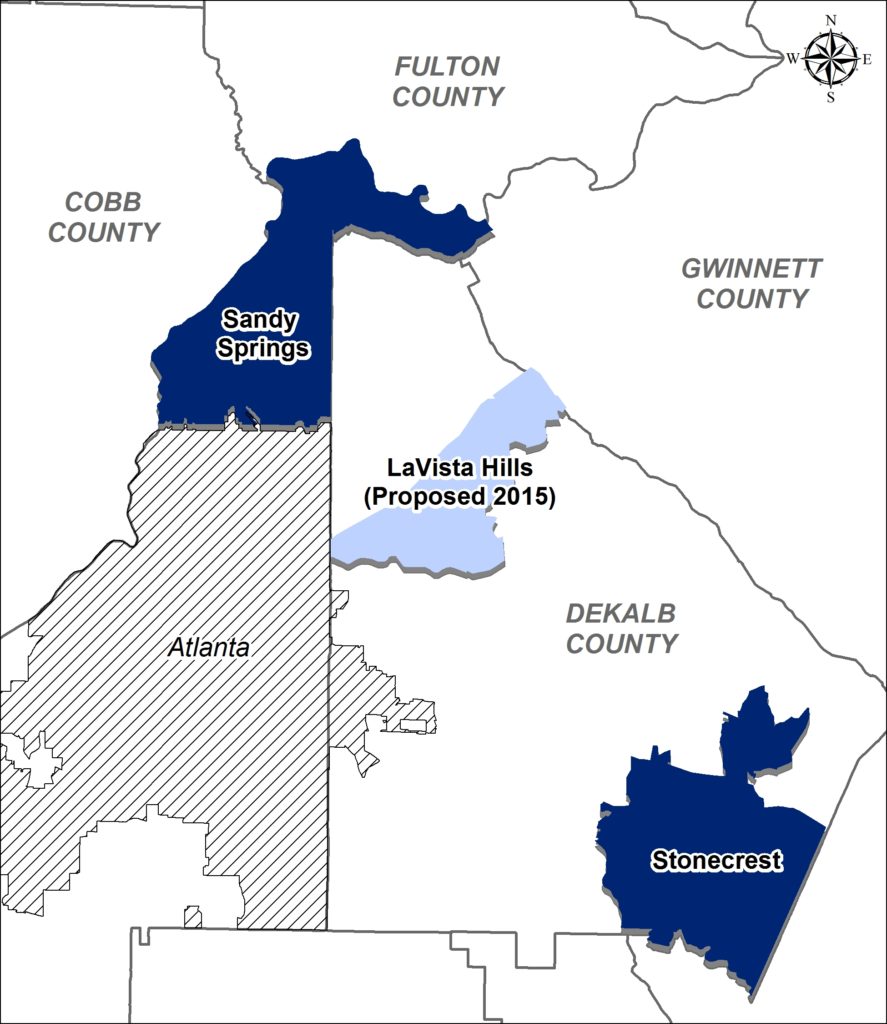

In the decade-plus since the 2005 incorporation of Sandy Springs, numerous cities have been created, predominantly in affluent, white areas articulated around the City of Atlanta. Sandy Springs was the first domino to fall, and its successful incorporation significantly lowered the political and programmatic barriers to entry for future cityhood initiatives in the State of Georgia. Recently-created cities in the Atlanta metro area include Johns Creek, Dunwoody, and Milton, among others. In DeKalb County alone, two high-profile incorporation bids have made the ballot—and headlines—in recent years: the City of LaVista Hills in north-central DeKalb failed in 2015 to attain the necessary votes to incorporate, while the City of Stonecrest in south DeKalb succeeded in 2016. In my work around these cityhood movements in Atlanta over the past two years, I have, like Rosen, encountered a strong aversion to discussions of race as part of the overall discourse around cityhood. Where I depart from Rosen is in my analysis of this phenomenon.

Anthropologist Charles Rutheiser, in his masterful text, Imagineering Atlanta,1 discusses the mechanisms of imagineering, the process by which Atlanta’s elite governance regime has, since mid-century and even before, worked to produce space and narrative in and around Atlanta. Rutheiser argues that this has been a concerted attempt to erase the fractious racial history of the city in order to hold up Atlanta as the business-friendly and culturally progressive City Too Busy to Hate, while at the same time reproducing the material and political conditions that have created and continue to bring about fractures.Pro-cityhood activists such as Jason Lary and Oliver Porter, and even opponents like Marjorie Snook, discuss cityhood in fundamentally ahistorical terms. And their rhetoric is a product largely of the hegemonic imagineering machine that has dominated politics and representation in Atlanta for decades. This limited spectrum of debates around cityhood ignores basic questions of how particular spaces (e.g. Sandy Springs, South DeKalb, Brookhaven, West and South Fulton, Dunwoody, and the Lakeside area that helped to birth the LaVista Hills movement) came to contain certain types of people, and how the presence of those people in those spaces directed or determined decisions around development, taxations, service provision, and, ultimately, power.To understand this ahistorical analytical approach, we must, following Rosen, turn to Oliver Porter. Porter was instrumental in developing the governance model for Sandy Springs, and is as close to a cityhood guru as one is likely to encounter in Atlanta.

Nevertheless, Porter makes it clear that he wants nothing to do with politics. Rosen quotes him as saying, “Compromise doesn’t make sense to me. It’s right or it’s wrong—there’s nothing in between.”2 Porter’s insistence that he is an apolitical actor motivated simply by what is right (in his case, economic efficiency and a distaste for progressive taxation)—and that Sandy Springs and other new cities are, by extension, apolitical entities—obscures the nature of what he considers to be apolitical and self-evident certainties but are actually deeply ideological and political claims about the ways in which the world does and should work.What Porter is attempting to perform is a sort of anti-politics that distorts the vulgar economism of his political philosophy. The anthropologist James Ferguson develops the concept of anti-politics in his study of development in Lesotho, The Anti-Politics Machine.3 In this markedly different context, Ferguson illuminates the desire of politicians, organizers, and experts to cast political decisions around governance and the state as simply questions of best practices or common sense. Returning to Porter: the anti-politics of cityhood constitutes an attempt to cast a rabid focus on the financial bottom-line as merely common sense. This concept of anti-politics, in conjunction with an imagineered history, is fundamental to understanding the operation of cityhood in Atlanta.For cityhood is political, as are the various actors arrayed around cityhood movements.

In particular, we might loosely characterize this economistic politics as a form of neoliberalism. Neoliberalism is a political economic regime characterized by an insistence on competitive relations and economic growth, a preference for individual property rights claims over other rights claims, an extension of economic relations into the realm of social relations, and a decreasing emphasis on universal participatory politics. Since its emergence in the Reagan/Thatcher years, neoliberalism has pervaded social life, transforming social relations, governance, space, institutions, and modalities of power. Despite neoliberal adherents’ claims or assertions, markets are neither natural, nor spontaneous, nor even necessarily efficient. Neoliberalism is not a return to an idyllic, free society. Rather, like all hegemonies, the neoliberal imperative becomes ossified in various civic and governmental institutions and apparati, and consequently in the collective sub-conscious, thus taking on an appearance of common-sense when in reality it is an ideologically-informed and state-supported construction.

The Master’s Tools

That Stonecrest was ever conceived in the first place is evidence enough that the old wounds still fester. There can be no doubt that the City of Stonecrest was imagined and incorporated as a bulwark against the further economic deterioration of underdeveloped and underresourced black communities: Marjorie Snook captures this dynamic in the Rosen piece: “It gets to a point where you’re completely surrounded by cities, and they all just selectively annex everything that’s valuable until there’s no tax base left.”4 And yet, in its incorporation, Stonecrest fails to challenge the logics of earlier cityhood movements, as well as the spatial hierarchies produced by historical movements for urban secession and segregation. Historically, movements for urban secession in wealthy, white areas in Atlanta were conceived as racial projects—a fact which Rosen accurately captures in his piece—and have had negative political, social, and economic implications for black communities. It is exactly this historical legacy into which Jason Lary and his supporters are wading.

There is more to this apparent tension between emancipatory potential and simple reproduction, and between histories of secession and current movements for black cityhood than Rosen allows. Audre Lorde, the great fighter and thinker, cautions us that the master’s tools “will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change.”5

Lary and other advocates of black cityhood generally fail to acknowledge or articulate a systemic and historical analysis of development, race, and the politics of space in Atlanta. Lary, for instance, is right in noting the difference in property values between white and black areas. But he stops short of questioning the fundamental reasons why that difference exists.

This tension is not ironic, as Rosen contends, but instructive and fundamental—indeed, indispensable—to understanding the politics of cityhood in Atlanta. This tension is the very crux of overlapping histories of white supremacism and capitalist development.

If we read Lary, Oliver Porter, and other proponents of cityhood as articulating a particular discourse around cityhood, the absence, the impossibility of this discourse is race. Not only does Stonecrest as it currently exists fail to fundamentally challenge the structures that produce racial inequity in Atlanta, it seems impossible that it could do so. The absence of a consideration of race and the emphasis on bare economics in arguments in favor of cityhood suggests to us that the cityhood movement—whether white or black in any given iteration—is, and largely wishes to remain, colorblind. But, as Eduardo Bonillo-Silva, Michael Omi and Howard Winant, and other scholars of race and racism have demonstrated, such colorblindness only serves to reproduce already-existing difference. 6 This colorblindness also represents a sort of historical rupture in black politics, a significant reversal from previous black middle-class movements in Atlanta—and elsewhere—which were explicitly race-conscious and advanced rights claims along explicitly racial lines.7Nevertheless, a temporary victory may seem or even be necessary, and indeed may constitute a positive outcome for the residents of Stonecrest, as the cityhood dominoes continue to fall and outcomes south of I-20 continue generally to lag, particularly post-recession.8

But if Stonecrest is a defensive structure, a product of Lary’s reading the writing on the wall, it seems unlikely to produce results beyond simply keeping the city’s collective head above water. Perhaps we should celebrate this result. But as Lorde insists, structural change is required in order to change the rules; until then, the game—as it has been for so long in Atlanta—seems likely to remain one of white supremacy and uneven development on a still-racialized landscape.A parallel concern revolves around the conceptualization of Atlanta as the (as-yet-unrealized) Black Mecca. The invocation of Atlanta as such coheres around a particular socio-political construction of the black middle class. Stonecrest embodies this very construction, with its emphasis on home values, economic development, self-sufficiency, and middle-class values more generally. And while a black middle class city does, at least nominally, challenge legacies of racialized capitalism and uneven development, it simultaneously advances a form of class warfare wherein a racially marginalized black middle class rejects solidarity with those they perceive as beneath them in order to compete. Thus, not only does black cityhood fail to challenge racial power structures, it also actively reproduces in a classist mode the exclusionary and extractive systems that create and exacerbate inequality in black communities.

Some Concluding Thoughts

There is no doubt that the City of Stonecrest represents an implicit acknowledgement of the reality of black history and marginalization in Atlanta. It embodies a significant opportunity for the black middle class in Atlanta to reclaim the promise of Atlanta as the Black Mecca, a promise which for so long has only been a partial, or, at best, qualified reality. But just as legal segregation became restrictive covenants became white flight became tax revolts, I fear that cityhood will remain a nominal improvement, as the racial and economic currents that have shaped space in Atlanta since its inception continue to predominate.

We must consider history and geography if we hope to move towards a more urgent and incisive politics around cityhood. We must confront the historical reality of space in Atlanta: it has been produced, and continues to be produced along racial lines. Anything that takes place on this landscape engages this history, willfully or otherwise. Places shift, and neighborhoods turn over, but the processes that have differentiated space in particular ways are much harder to halt or redirect.We should condemn cities and other political configurations that invest in racialized and historically-accrued material and political advantage, such as Sandy Springs.

And we should celebrate self-determination of black communities like Stonecrest in a metropolitan area that has for so long denied that basic right. But we must also search for the unasked questions, the buried histories, the impossibilities in the stories we think we know about Atlanta, and excavate the kernels of alternative realities to build alternative futures that these stories obscure or preclude. The master’s house still stands. If we wish for equity in Atlanta, we must name every brick, and pull the walls out piece by piece.

Citation: Allums, Coleman. “Anti-Politics and the Impossibility of Race: Reflections on Urban Secession in Atlanta.” Atlanta Studies. May 16, 2017. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20170516.

Notes

- Charles Rutheiser, Imagineering Atlanta: The Politics of Place in the City of Dreams (London: Verso, 1996).[↩]

- Sam Rosen, “Atlanta’s Controversial ‘Cityhood’ Movement,” The Atlantic, April 26, 2017, https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2017/04/the-border-battles-of-atlanta/523884/.[↩]

- James Ferguson, The Anti-Politics Machine: Development, Depoliticization, and Bureaucratic Power in Lesotho (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press: 1994).[↩]

- Rosen, “Atlanta’s Controversial ‘Cityhood’ Movement.”[↩]

- Audre Lorde, Sister Outsider (New York: Ten Speed Press, 2007 [1984]), 112.[↩]

- See: Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, Racism without Racists: Color-blind Racism and Racial Inequality in Contemporary America (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2010) and Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United States (New York: Routledge, 2015).[↩]

- For example, see: Clarence Stone, Regime Politics: Governing Atlanta, 1946–1988 (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1989). Other germane writings include W. E. B. Du Bois, The Souls of Black Folk: essays and sketches (Chicago: A.C. McClurg & Co., 1903); James Baldwin, The Fire Next Time (New York : The Dial Press, 1963); and Martin Luther King, Jr., Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? (New York: Harper & Row, 1967).[↩]

- See: Emily Badger, “‘This Can’t Happen by Accident.’,” The Washington Post, May 2, 2016, https://www.washingtonpost.com/graphics/business/wonk/housing/atlanta/, and Karen Pooley, “Segregation’s New Geography: The Atlanta Metro Region, Race, and the Declining Prospects for Upward Mobility,” Southern Spaces, April 15, 2015, https://southernspaces.org/2015/segregations-new-geography-atlanta-metro-region-race-and-declining-prospects-upward-mobility.[↩]