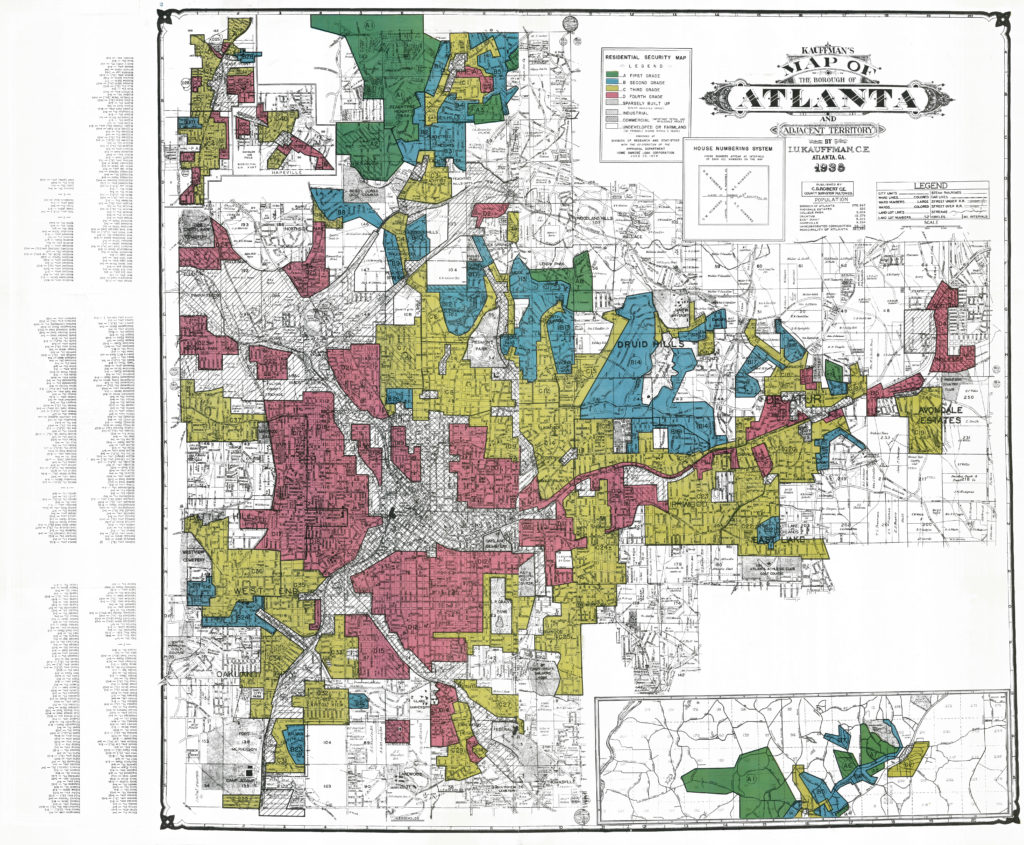

In 1938, as part of an effort to survey the nation’s cities to estimate neighborhood risk levels for long-term real estate investment, the federal government’s Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) produced a “security map” of Atlanta.

This map and accompanying documents, recently published as a searchable layer in ATLMaps, divided the city into 111 residential neighborhoods, and assigned each neighborhood a grade, from A to D, which indicated the projected trend of property values in the area, and thus the level of “security” it offered – or the risk it posed – to grantors of home loans. The “area descriptions” which accompany the map reveal that for the HOLC, property values derived from social exclusion: HOLC appraisers awarded a grade of A or B to neighborhoods with high levels of homeownership and racial restrictions on the sale of property, and stamped grades of C or D on areas where renters and non-whites resided. For instance, they cite “proximity to negro property” and “infiltration of lower income groups” as “detrimental influences” which lower a neighborhood’s “security rating,” while black neighborhoods, even those housing professors, professionals, and businessmen around Atlanta’s black universities, are universally marked “D.”1

The HOLC survey privileged neighborhoods comprised exclusively of white homeowners for purposes of property appraisal and loan disbursement. This logic was to govern the Federal Housing Administration’s massive program of government-backed mortgage loans, which underwrote the post-WWII suburbs while redlining areas housing those from whom white property values were deemed in need of protection.2 It perhaps comes as no surprise that the federal government’s projections of “future value” for people and the neighborhoods in which they resided became self-fulfilling prophecies, as they provided the basis on which home loans were made. After World War II, the systematic channeling of resources into areas occupied by white homeowners and away from those housing non-whites and renters, coupled with barriers to entry designed to ensure that the demographics of neighborhoods deemed favorable for the maintenance of property values did not change, resulted in a predictable geography of poverty and privilege, prosperity and despair, drawn largely along racial lines. The resulting landscape provided a powerful visual confirmation of the race and class logic on which it was based, as the material inferiority of neighborhoods housing those deemed inimical to property values was often taken as justification of the very strategies which had produced it.3

Such practices of exclusion, and the justifications provided for them, shaped new racial and political identities, as the “neutral” language of property values and “the market” was increasingly deployed in defense of the geography of white privilege, largely replacing appeals based on claims to white racial superiority common earlier in the twentieth century.4 The irony of racial privilege backed by massive federal subsidy and restrictive local land-use regulations being defended with appeals to “the market” has not been lost on commentators,5 but did not prevent the “market logic” which informed the politics of exclusion at the local level from being transferred to political discourse at national scale. As Kevin Kruse informs us, these tropes from the local politics of neighborhood exclusion were written into the Republican Party’s “Southern Strategy” appeal to suburban whites, with those denied access to suburban neighborhoods in the name of property values to be similarly denied a seat at the table of federal largesse, all in the name of the “free market.”6

As I argue in “The Value of Exclusion: Chasing Scarcity Through Social Exclusion in Early Twentieth Century Atlanta,”7 it would be hard to overstate the significance of the 1938 HOLC Atlanta Residential Security map, and its accompanying neighborhood descriptions, for the future shaping of the city, and for contemporary understanding of the geographies of poverty and privilege which shape the city today. Despite the significance of these documents, however, they have been essentially inaccessible to Atlantans and others who might be interested in reading them, as viewing them required a trip to the National Archives and Records Administration in College Park, Maryland. It would take the research of Kennesaw State University historian LeeAnn Lands to not only call attention to the significance of the HOLC’s “Residential Security Map” of Atlanta in The Culture of Property: Race, Class, and Housing Landscapes in Atlanta, 1880–1950, but to scan the contents of the HOLC’s Atlanta folder, bring them back to Atlanta, and generously make them available to other scholars of the city. We all owe LeeAnn a great debt of gratitude, as without her efforts and generosity, these documents would not have been published online. Also deserving of thanks is the University of Richmond’s Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America project, which has provided online access to the HOLC’s “redlining maps” for cities across the country. Our layer complements and extends that project by also making available, in searchable format, the HOLC’s neighborhood descriptions which accompanied its 1938 map of Atlanta. Moreover, this format allows analyses of more contemporary maps of the city to be made in light of this original data.

The historical significance of the HOLC’s “red-lining map” of Atlanta, and its shockingly blunt application of a neighborhood rating system which promised privilege for white homeowners, and exclusion for non-whites and renters is clear. Hopefully the publication of these documents will also invite efforts to further unpack the hidden details of these maps and the processes behind them, and link analysis of contemporary challenges facing Atlanta’s neighborhoods to the history contained within them. Ultimately, the vast inequities that exist in today’s Atlanta with respect to treatment by the criminal justice system, and access to jobs, housing, education, and health care, can only be better understood, and hopefully overcome, by a critical understanding of the neighborhood-based, discriminatory practices of home mortgage lending that are laid bare in these HOLC documents. It is exciting that these documents have finally been put where they belong, in an easily accessible public domain.

Note: Portions of the above have been republished, with permission, from Jason Rhodes, “Finding Value in Racism: The Spatial Choreography of Black and White in Early Twentieth Century Atlanta,” PhD diss., University of Georgia, 2013, https://getd.libs.uga.edu/pdfs/rhodes_jason_201308_phd.pdf; and Jason Rhodes, “The Value of Exclusion: Chasing Scarcity Through Social Exclusion in Early Twentieth Century Atlanta,” Human Geography 9, no. 1 (2016): 46–67.

Citation: Rhodes, Jason. “Geographies of Privilege and Exclusion: The 1938 Home Owners Loan Corporation “Residential Security Map” of Atlanta.” Atlanta Studies. September 07, 2017. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20170907.

Jason Rhodes is a Lecturer in the Department of Geography and Anthropology at Kennesaw State University.

Notes

- The “newer portion of West End,” or Area C-36 in the report, has its “proximity to negro property” cited as one of its “detrimental influences,” while area C-7, the “section between Sixth and Sixteenth Streets and State and Spring Sts.,” is declared a poor candidate for mortgage loans in part on the basis of the “infiltration of lower income groups” noted by the HOLC. See also the area description for area D-17, the neighborhood surrounding Atlanta University, which HOLC appraisers label the “best negro section in Atlanta.” Home Owners Loan Corporation, “Residential Security Map, Atlanta Georgia” folder: Atlanta, box 82, RG 195, Records of the Federal Home Loan Bank Board, 1933–1983, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland; “Security Area Descriptions.”[↩]

- An impressive literature has emerged to document the details and assess the consequences of such race and class-based strategies of exclusion. See: Kenneth T. Jackson, Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985); Thomas Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1996); Robert O. Self, American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2003); Kevin Kruse, White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005); David M. P. Freund, Colored Property: State Policy and White Racial Politics in Suburban America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007); LeeAnn Lands, The Culture of Property: Race, Class, and Housing Landscapes in Atlanta, 1880–1950 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2009).[↩]

- Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis, 8.[↩]

- Freund Colored property, 8–9.[↩]

- In particular, see Freund, Colored Property: 121, 163–73.[↩]

- Kruse, White Flight: 259–66.[↩]

- Jason Rhodes, “The Value of Exclusion: Chasing Scarcity Through Social Exclusion in Early Twentieth Century Atlanta,” Human Geography 9, no. 1 (2016): 46–67.[↩]