Much of the Unpacking Manuel’s Tavern project has consisted of chasing stories of past patrons.

Tidbits, leads, and clues, combed out of the hours of oral history interviews with the long-time staff, owner, and regulars of the Tavern, told and recorded both before and after the renovation. An offhand comment from one of the first of these interviews ended up leading me to the story of an Atlanta artist, Dean Chapman.

The comment was simple: he was an artist who sometimes paid his bar tab off with a painting, said with an offhand wave at one of several of his paintings. Little else turned up in supplemental interviews. Yet, as I started to catalogue and research the Manuel’s Tavern collection, I kept returning to these paintings, my eye catching on one, then another, and another, until I just had to know: who was Dean Chapman?

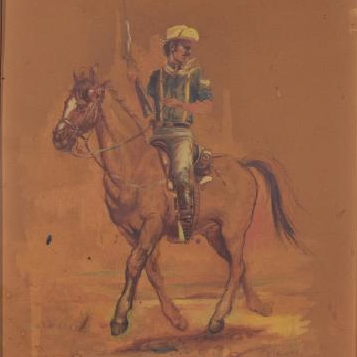

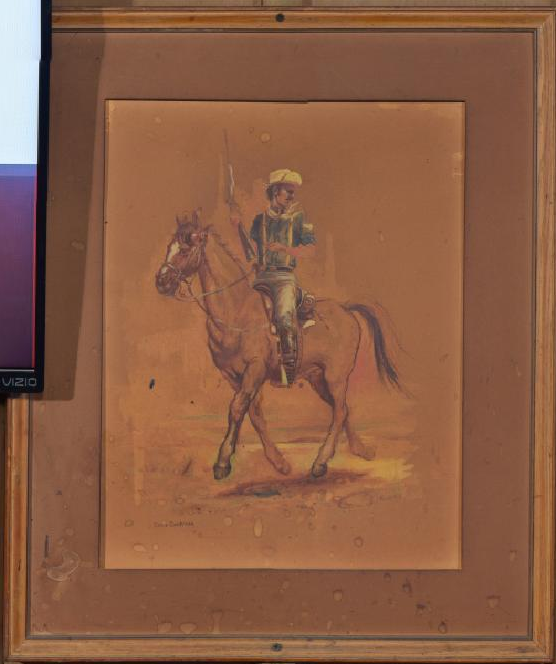

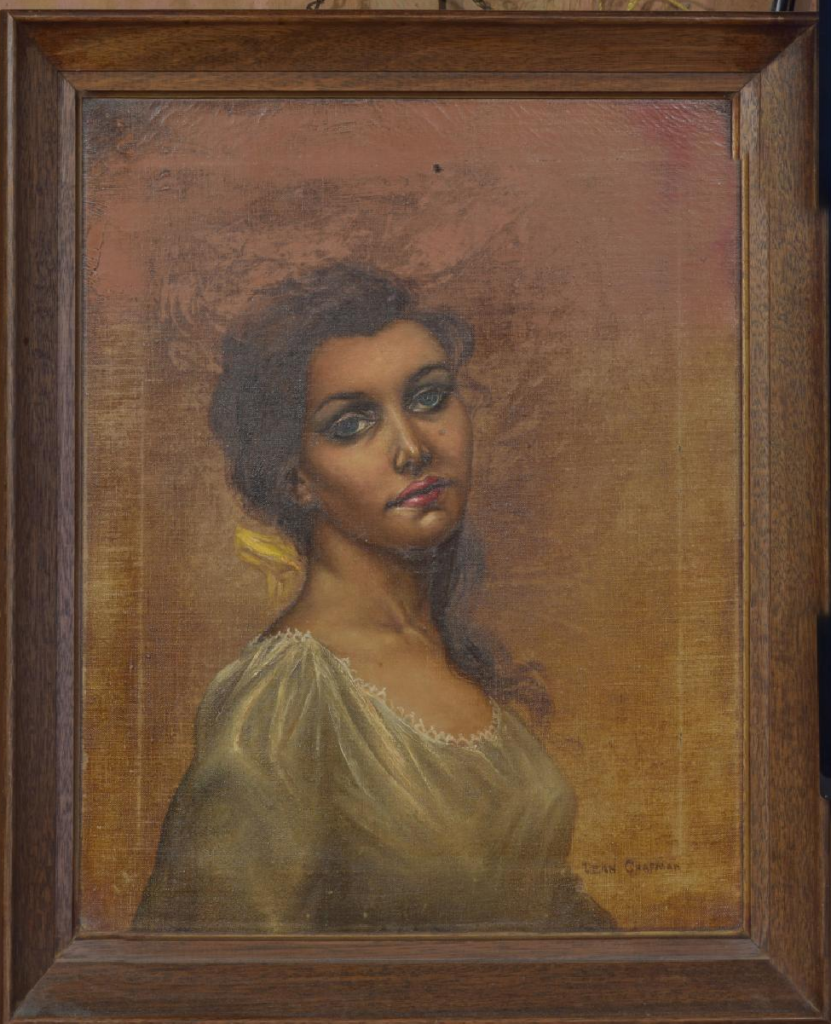

Two of his paintings once hung in the main dining area of Manuel’s Tavern: one, a portrait of a young woman in a peasant blouse with a tan background, the other, a US Cavalry soldier on a bay horse the same color as the background. Several others of his paintings adorned other rooms of the Tavern, including the breezeway to the main bar. His style is distinct, and even without Chapman’s signature the paintings’ style easily groups them together, mixed in among the abstract art, impressionist landscapes, and myriad photographs and bar ephemera that cover most of the walls.

Even after two years of working with the Manuel’s Tavern collections, I still come back to these paintings, due to both what I know, and what I don’t, about this man and his work. Once I started combing through art dealers and auction catalogues, it was easy to turn up some basic information.1 Born in 1937, and passing away in 2001, Dean Chapman was known for his paintings of the “Wild West,” or as it is often put in the auction listings for his work: “western genre and cowboy paintings.” In my mind, I envisioned the sort of works that graced the cover of the sorts of books my grandfather read, with the lonesome cowboy and that one valley in Utah that was in every western movie.

The painting of the US Cavalry solder is deceptive. At first glance it shows you the nearly John Wayne-esque figure astride a bay quarter horse with white blaze, all four hooves off the ground in a bouncy trot.2 Looking closer, however, the image becomes less Hollywood and more historical. The soldier is shown looking back and away, his face a mix of features that would have been far more likely in the historic American West. Small details, like the horse’s bit and bridle, the hornless saddle, and the position of the rifle and belt pistol, all expose a hand obsessed with the minute details of its subject. The horse wears a tie-down strap, holding its head down rather than letting it look up, a device often used in horses which “stargaze,” and one can see the faint whites in the lower part of the horse’s eyes, as it looks up in just such a behavior.3 Even in a rough color study, after decades of water and smoke damage, these small details stand out.

The story of Dean Chapman, as I learned, was much the same.4 In rough outline it was a standard story: he was a talented artist, even as a young adult, enlisted in the military and fought in World War II, suffered from alcoholism, had money problems, and family problems, and ultimately died in relative obscurity. But in the details, Dean Chapman was more complex, his story no longer the standard Hollywood character arc, but rather a much more interesting one, with odd turns and a structure no editor would allow.

Chapman was captain of the football team at Avondale High School, athletic and apparently well-liked in high school, but, even then, already well on his way to his career as an artist.5 Major names from the art world dot his early training, including George Beattie (painter of the recently controversial agricultural mural series once housed at the Georgia Department of Agriculture’s Atlanta office).6

Under Beattie, Chapman met Ben Shute, then director of the Art Institute of Atlanta, who encouraged Chapman to apply for a scholarship to the school.It was while a student at the Art Institute of Atlanta that Chapman first really appears in the Atlanta popular histories. In his early 20s, he painted a number of portraits of local, and then national, political figures. These include a portrait of Principal J. E. Burgess of Avondale High School, and one of Ben Burgess, clerk for the DeKalb Superior Court.7 In addition, he painted portraits of Major General George G. Finch, Commanding General 14th Air Force, Actor Ricky Nelson (whose portrait was featured in People Magazine), and even Richard Nixon. He continued his career while enlisted, as an artist in the military, and served with the Georgia Air National Guard, stationed at Dobbins Air Force Base. After his service, Chapman believed that he could survive only as an artist, and did so for the rest of his life, though money trouble would always shadow him. It is during this period, that the story of Chapman returns to Manuel’s Tavern. A regular for decades, Chapman apparently often paid his tab with paintings, which explains their inclusion in the collection.

Chapman reportedly struggled with alcoholism early in his life, later joining AA after divorcing his last wife. Even still, he reportedly continued to struggle with issues of anger and ego. Yet according to one of his daughters, Clarissa Chapman, he was a caring father who later warned his children away from his own mistakes of the past. She recalls that he always wore cowboy boots, and proudly (though without documentation) claimed their family to be part Choctaw and Creek. This identity threw, for me, the dynamic, often powerful images of the Native Americans of the Great Plains, which feature heavily in his work, into a different light. The detail of the dress, of the weapons, of even the methods of combat, suddenly became more understandable, less the Hollywood Old West and more the historical reality.

The woman in the portrait shows a much similar depth of hidden detail as the Cavalry soldier. From across the room, it seems simply a portrait of a young woman, almost casual in her pose. But close inspection reveals a strange set of mixed images. Her eyes are blue, looking at the viewer, but show details of tiredness and stress. A beauty mark on her cheek draws the eye away from the tension around her eyes, and starkly red lips even further. Her hair is brown, as disheveled as the mane of the soldier’s horse. Her blouse, with careful lace trim, reveals one of the details of Chapman’s figure methods with its slight transparency: painting first the nude body and then adding clothing over the underpainting. I noticed one detail only after months of looking closely at the painting: the cloth with which she has her hair tied back is the same yellow as the bandana of the Cavalry soldier.

A small detail, and yet my eye catches on it every time that I see it now. I wonder if the paintings were intended as a set, or if the color of the bandana is merely to link her into the narrative of the Old West. I like to think of the two paintings as a pair. In the fiction of the painted world, is the stress in her eyes worry for the Cavalry soldier, or simply for the harshness of life in her time? I do not know the answer. Like so much in Chapman’s life, the details of the paintings add only questions, not answers.

Citation: Creighton, Ness. “Paying the Tab in Paint: Dean Chapman and Manuel’s Tavern.” Atlanta Studies. October 10, 2017. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20171010.

Notes

- “Dean Chapman,” MutualArt, last modified 2017, https://www.mutualart.com/Artist/Dean-Chapman/C01E3C6D8D61E273.[↩]

- Dean Chapman, “Untitled,” Manuel’s Tavern, Atlanta, GA.[↩]

- Elwyn Hartley Edwards, Complete Bits and Bitting (Newton Abbot, UK: David & Charles, 2004).[↩]

- Clarissa Chapman, “Dean Chapman (1937–2001),” askART, Accessed September 1, 2017, http://www.askart.com/artist_bio/Dean_Chapman/124135/Dean_Chapman.aspx.[↩]

- Andrew Sparks, “Samson’s Battle Comes to Life on 33-Foot Painting,” Atlanta Constitution, March 15, 1959.[↩]

- Pasty Dudley and Pate Balcony, “George Beattie’s Agriculture Murals,” Georgia Museum of Art, accessed September 1, 2017, http://georgiamuseum.org/art/exhibitions/on/george-beatties-agriculture-murals.[↩]

- Here, a detail, smudged in the memory of history, makes itself known. For those unfamiliar with the history of DeKalb County, Georgia, there have been multiple people by the name of Ben Burgess who served in this position, all family members. Whether this portrait was of Ben F. Burgess (Clerk 1923–35), Ben B. Burgess (1935–56), or one of the earlier B. Burgesses, is unknown. I have also run myself in circles trying to pin down if, in fact, Principal Burgess was from the same large, influential, and extended family (more than likely), or simply had the same last name by coincidence.[↩]