Sports as a central part of American culture has become a growing part of scholarship across a wide range of humanities fields.

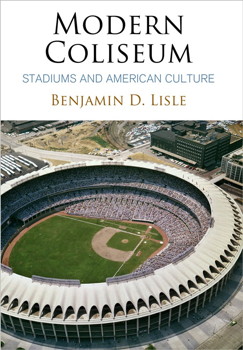

With the popularity of blogs such as Sport in American History, or the continually high ratings of ESPN’s 30 for 30 series of documentaries, people are more interested than ever in consuming every aspect of sports and sporting culture. It is in this context that Benjamin Lisle’s Modern Coliseum: Stadiums and American Culture proves to be a vital addition to the growing list of books that seek to explain the intersection of sports, popular culture, and politics in American society, such as Louis Moore’s I Fight for a Living: Boxing and the Battle for Black Manhood, 1880-1915 and Cory Hillman’s American Sports in an Age of Consumption.1 For Lisle, the history of American stadiums is ultimately a mirror for the history of the United States after World War II as race, gender, economics, and civic responsibility all played roles in shaping how new stadiums developed in cities across the United States. As Lisle writes, “these modern coliseums tell us a great deal about who we were, who we aspired to be, how we experienced space and the city, and how we conceived of ourselves as a public” (12).

Certainly, these are high aspirations for a book “just” about sports stadiums. But through meticulous use of archival sources, Lisle recounts a powerful story about sports stadiums in mid-twentieth-century America, the political boosterism behind their construction, and how having a state-of-the-art sports facility became of critical importance to city leaders. As Lisle puts it, “the arrival of a big-league team, as a civic status symbol,” was important to mayors, city councilmen, and business leaders across the nation (63).Though Atlanta’s emergence as a “major league” city in the 1960s is not one of the cases Lisle examines in the book – those include Brooklyn, Houston, Milwaukee, Baltimore, San Francisco, and Los Angeles – the insights about how sports and the stadiums they were played in were important parts of post-war civic boosterism are nonetheless relevant and illuminating in our local context. Southern cities like Atlanta, Charlotte, and New Orleans ultimately saw the same rationale for attracting sports teams as their midwestern and western counterparts: it made them appear to be major cities.

Within this need to attract major league teams to appear to be major league cities, however, was concern over racial divides in society. Post-World War II Brooklyn was held up as an exemplar of Cold War era tolerance and diversity.2 Notably, Atlanta’s own reputation as the “city too busy to hate” was also created during this time period. That helped the city sell itself to potential investors and to professional sports leagues. Combine this with the economic trends of post-World War II America – including white flight to the suburbs – and it is hardly surprising that modern stadiums were often located in places most easily accessible by car, closer to the suburbs, and far away from the tumult of crime, economic decline, and blackness. This is, of course, a story familiar to sports fans in Atlanta, as it played a part in the decision to move the Braves from downtown Atlanta to Cobb County.

Lisle takes great pains to examine how the idea of the stadium evolves over time. In chapter 1 he writes of the neighborhood stadium that once permeated American society. This was seen in places such as Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field – but, to bring it closer to Atlanta, old Ponce de Leon Park as well, where both Atlanta’s minor league baseball team as well as its Negro League team, the Atlanta Crackers and the Atlanta Black Crackers respectively, played. However, as Lisle explains, the idea of modern stadiums such as Houston’s Astrodome and the Atlanta–Fulton County Stadium in Atlanta – which weren’t in “old urban neighborhoods” but instead were “convenient to booming white suburbs” – would come to dominate the thought behind the why and how of building a sports stadium for the rest of the twentieth century (5–6).

For example, Atlanta’s desire for a professional sports team, and the building of a stadium to attract said team, transcended all other considerations for the development of Summerhill in 1966. Thirty years later, the construction of Turner Field – originally Olympic Stadium – displaced many of Atlanta’s poor, providing a model for other Olympic cities on how to deal with populations they wanted out of sight. Later, the creation of Sun Trust Park in Cobb County created distrust among many fans in downtown Atlanta, as they saw the team move from a largely black downtown to mostly white Cobb County.3

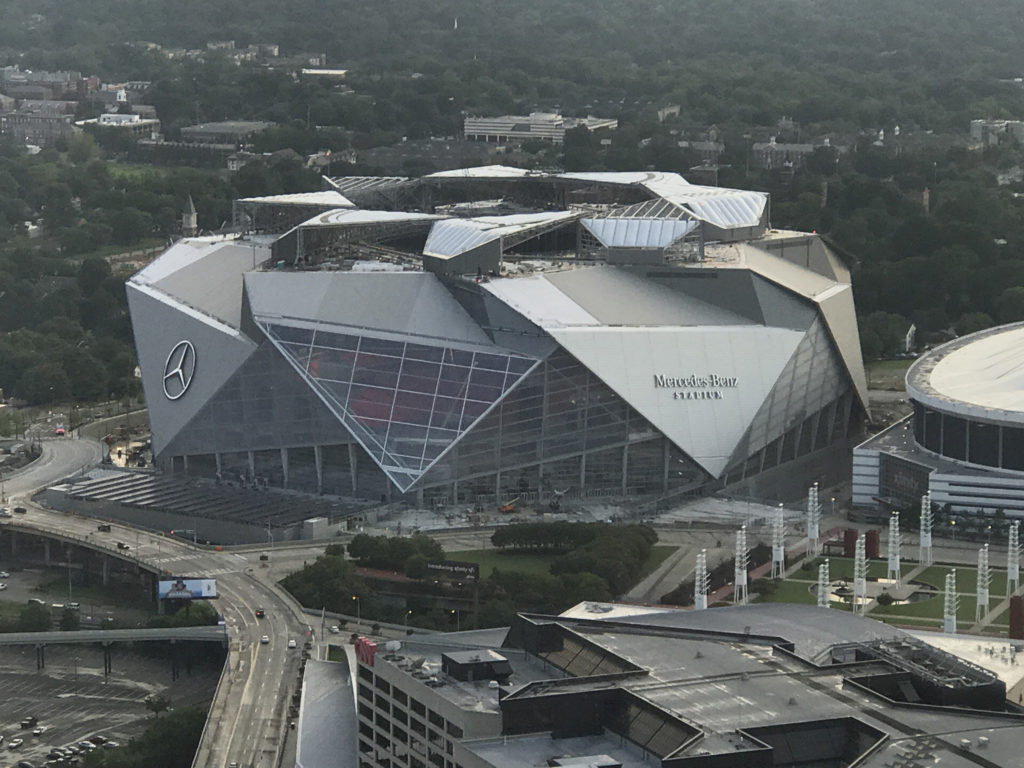

More recently, the creation of the new “modern marvel” Mercedes-Benz Stadium meant the tearing down of Friendship Baptist Church, a historic African American church that was the early home for Spelman College and the first location for Morehouse College after it moved to Atlanta from Augusta, Georgia, in 1879.4 In that case, the civic religion embodied in modern sports stadium – intended to both boost a city’s pride and reputation – clashed with literal religious belief in Atlanta and ultimately won.

Though the only southern city Lisle examines in depth is Houston, as a leader of both the New South and the Sunbelt, Atlanta, with its complicated relationship to professional sports after 1966, tells a story of racial reconciliation and economic development that deserves a book of its own. Whoever sets out to write such a needed book will find a worthy model in Benjamin Lisle’s Modern Coliseums.

Citation: Greene II, Robert. “Book Review: Modern Coliseum: Stadiums and American Culture.” Atlanta Studies. October 20, 2017. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20171020.

Notes

- Louis Moore, I Fight for a Living: Boxing and the Battle for Black Manhood, 1880–1915 (Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2017); Cory Hillman, American Sports in an Age of Consumption: How Commercialization is Changing the Game (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2016).[↩]

- Books such as Jason Sokol’s All Eyes Are Upon Us: Race and Politics from Boston to Brooklyn (Philadelphia: Basic Books, 2014) complicate this narrative. As does Lisle himself, pointing to the ways in which the growing racial diversity around Ebbets Field in Brooklyn became an economic liability in the eyes of Walter O’Malley, owner of the Dodgers[↩]

- Andy Walter, “Mapping Braves Country,” Atlanta Studies, November 2, 2015, https://atlantastudies.org/mapping-braves-country/.[↩]

- Ironically, Mercedes-Benz Stadium has also been referred to as a “secular cathedral” due to its majesty. Its story resembles that of many other recent stadium construction projects. See: Steve Fennessy, “American Cathedral: The Story Behind Mercedes-Benz Stadium,” Atlanta Magazine, September 2017, http://www.atlantamagazine.com/great-reads/american-cathedral-mercedes-benz-stadium/.[↩]