If there is a silver lining to the frigid temperatures that gripped the southern United States in early 2018, it’s that those cold nights give promise to a more successful peach crop in Georgia.

As many may recall, it was only a year ago when an unseasonably warm winter coupled with a late frost devastated nearly 80 percent of the state’s peaches, making the favored fruit scarce even in local markets. Around the time when growers and consumers were expressing concern over the future of southern peach culture, William Thomas Okie’s new book The Georgia Peach: Culture, Agriculture, and Environment in the American South was published, revealing how recent climatological events are simply another episode in a long history of challenges that Georgia peach growers have faced over the past century and a half. The book also opens a deeper understanding of this fruit’s complex past and its enduring symbolic power. The physical footprint of peach production in Georgia is not particularly strong with peach trees covering only 11,816 acres in 2014 and paling “beside the 1.38 million acres of cotton, 607,272 acres of peanuts, and 28,643 acres of blueberries” (4). Yet, the peach’s cultural presence is pervasive across the state and is particularly present in Atlanta where at least seventy-one streets contain a variant of “Peachtree,” and similarly branded popular events include the annual college football Peach Bowl now in its fiftieth year and the culinary PeachFest that debuted last summer.

Okie, an environmental historian at Kennesaw State University, is a fitting author to unravel the history and myth surrounding the Georgia peach as his intimate knowledge and interest stems not only from archival research but also from experiences with his father, who retired in 2011 after thirty years of breeding peaches at the USDA Research Laboratory in Byron, Georgia. Although Okie briefly traces the peach back to its origins in East Asia, his narrative begins in the early 1850s when Dennis Redmond of Augusta established his 315-acre Fruitland Nursery – internationally known today as the exclusive site of the Masters Golf Tournament. Father and son, Louis and Prosper Berckmans, Belgian immigrants and educated horticulturalists, soon purchased Fruitland. Influenced by the theories espoused by landscape architect A. J. Downing, the Berckmans “intended to remake the South” into a more civilized, beautiful, and prosperous place “by disseminating the knowledge and the plant material of fruits and ornamental plants” (31). Before long, Fruitland was one of the largest nurseries in the South, representing “an outpost of European horticulture” (45).

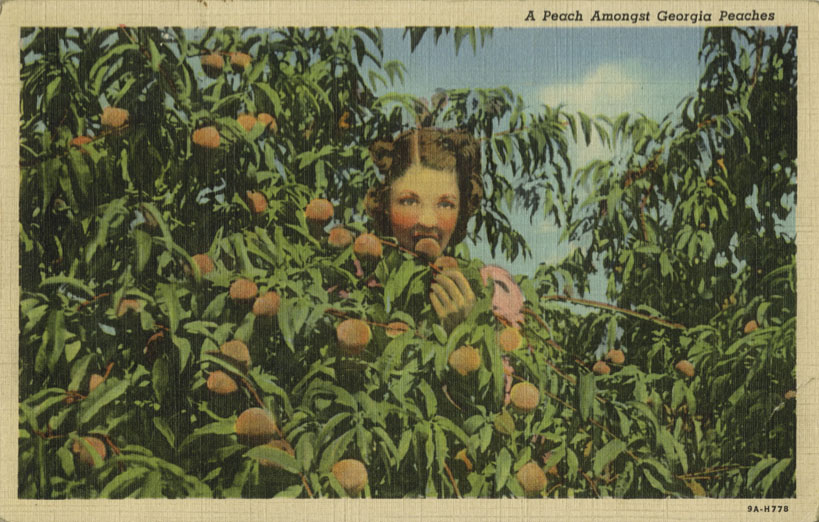

The Berckmans certainly advanced horticulture and diversified agriculture, although Okie’s representation of this duo as the start of something new in Georgia minimizes a longer story of experiments dating back to the state’s founding. But Okie’s emphasis on this crucial period fits his intention to show how the peach’s success as a commercial crop and development into a cultural icon occurred at a specific time and place in Georgia’s history.According to Okie, after Reconstruction commercial horticulture in the southern states became viable as sectional hostilities waned, northern markets opened, cotton farmers sought to diversify their crops, and ex-slaves provided an essential labor force for harvesting fruits. Still, other factors likely included the development of railroads and the growth of Atlanta and other cities. Around this time, horticulturalist Samuel Rumph of Marshallville introduced his Elberta peach cultivar, an offspring of the Chinese Cling which he named after his wife. The Elberta peach offered great commercial potential because of its ability to be picked green and easily shipped to distant markets. Moreover, the highly feminized and racialized peach – “soft and sweet and blushing, … like white southern maidens” – provided an image and product of Georgia capable of attracting outside capital (85). As the 1895 International Cotton States Exposition in Atlanta emphasized industry, “the industrial dream could not do without horticulture,” leading Berckmans’s Fruitland Nursery to provide a “scenic backdrop” of greenery “for the drama of the New South that was to play out on that stage” (84).

With the exposition conveying “the unmistakable message that the South was all set for industrial development,” Okie contends that “horticulturists offered the corollary that development could also mean a more beautiful landscape” (84) This agricultural-beauty nexus within the context of the white supremacy, racial violence, and African American disenfranchisement that marked the Jim Crow Era perhaps deserves more attention than Okie pays it.

Near the turn of the century, capital arrived in Georgia through individuals such as John Howard Hale – “a self-described Yankee who ran his two-thousand-acre farm near Fort Valley as a factory” powered by an African American workforce (88). With other investors following Hale’s lead, peach growing rapidly expanded in the early 1900s. As Okie summarizes the changes marking this period: “Northerners bought up land; southern growers made deals with railroad and commission merchants; urban consumers learned the Georgia peach by name; rural African Americans saw their options foreclosed and started moving away from the field” (112). Despite the growth of the industry, commercial peach growers were not without their challenges, as the delicate and perishable nature of the fruit made the business venture a costly and unpredictable one (114). But large-scale commercial growers found support in the USDA, along with other state and federal agencies that established research stations and developed new pest control technologies. In 1908, Georgia growers organized the Georgia Fruit Exchange, reconstituted in 1923 as the Georgia Peach Growers’ Exchange. The exchange, however, turned out to be “more a corporation than a cooperative” finding ways to control market forces through distribution, advertising, and sales (124)

As the Georgia peach industry became “caught up in a wider web of distribution and marketing agents” in the 1910s and 1920s, growers focused on further developing the peach’s local identity (142). For example, Mabel Clare Withoft, who moved with her husband Frank from Dayton, Ohio, to Fort Valley, Georgia, in 1908, helped shape this identity by producing a significant poetry collection inspired by the Georgia peach (147). Withoft also organized an annual peach blossom festival for the town and wrote a peach pageant that garnered national attention – actions that contributed to the eventual founding of Peach County in 1924. However, as Okie points out, the boundaries for the new Peach County, which encompassed much of the urban populations (and the accompanying wealth and power) of the surrounding Houston and Macon counties, attest to the campaign’s association with a movement toward white rural progress. As a counter-narrative, Okie also includes a detailed history of Henry Hunt, the president of the Fort Valley High and Industrial School and an African American rural reformer, who worked to improve the lives of the field laborers responsible for making peach growing profitable. Okie’s careful selection of the figures he profiles, such as Withoft and Hunt, enable him to unpack the oft-obscured racial tensions underlying Georgia’s peach mythology.

Despite Hunt’s efforts, rural life in middle Georgia would undergo significant changes in the decades following World War II. “Slowly, farmers transitioned away from the local, rural black labor that had sustained southern agriculture for generations,” Okie explains, “relying instead upon an ever-widening labor circuit: urban African Americans, World War II POWS, Caribbean migrants, undocumented Latinos, and, more recently, Mexican guest workers” (180). The latter half of the twentieth century also brought about new pests and pathogens, as well as new pesticides and application methods, in addition to the establishment of a federal laboratory in Byron to rescue the state’s rapidly shrinking industry. While scientific experimentation has brought about better adapted rootstocks and technological advancements have made packinghouses more efficient, peach harvesting remains dependent on manual rather than mechanized labor due to the fruit’s delicacy and perishability. As Okie concludes, “The permanence of the South’s signature product depends upon impermanence, a transfusion of rural Mexico into rural Georgia, a transitory repopulation of the rural South” (215). It is hard not to imagine that the recent wave of anti-immigration sentiment and policy will open a new chapter in the saga of the Georgia peach alongside global climate change.In his book, Okie covers much more than simply the Georgia peach, interweaving horticultural history with agricultural, environmental, and labor history, and building off an extensive body of literature from these fields. His strong focus on the section of the Black Belt that spans middle Georgia might leave some readers wondering how the history of the peach in Georgia compares or contrasts to other parts of this peach-growing region that extend beyond the state’s boundaries into Alabama and South Carolina.

This focus also raises the question of how representative the Georgia peach is of “Culture, Agriculture, and Environment in the American South,” as the book’s subtitle claims. A more critical regional approach might have helped to deconstruct this broad generalization. Aside from the stories about Withoft, the book perhaps provides less insight about the popular culture surrounding the peach than might be expected; in particular, Okie emphasizes the myth’s creation rather than its perpetuation through acts such as imprinting the “Peach State” on license plates in the late 1940s or Atlanta’s New Years’ Eve “Peach Drop” begun in 1989. Still, the combination of Okie’s accessible and fluid writing style and the depth of his research will make this book appealing to general audiences and academics alike.

Citation: Bryan, Stephanie. “Book Review: The Georgia Peach.” Atlanta Studies. April 03, 2018. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20180403.