In December 2017, Atlanta Public Schools (APS) Superintendent Meria J. Carstarphen and then-Mayor Kasim Reed announced a partnership to create an interactive curriculum based on Atlanta City Design: Aspiring to the Beloved Community, a nearly 400-page document made available in September 2017 by the Department of City Planning.

Starting as a pilot program in selected middle schools in early 2018 1, the curriculum is scheduled to become part of ninth-grade social studies courses during the 2018–19 school year. With this new program, Atlanta becomes part of an emerging nationwide trend to educate students about civics and urban planning.2

But despite the prevailing rhetoric that “this new partnership is highly unique and represents the first time the city and APS have collaborated to develop a curriculum of this type,”3 Atlanta launched a nearly identical project seventy years ago. If the authors of Atlanta City Design believe, as they have written, that “the first step in city design is to understand who we are and where we came from,”4 then learning about the successes and shortcomings of the city’s past foray into urban planning education is essential.

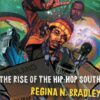

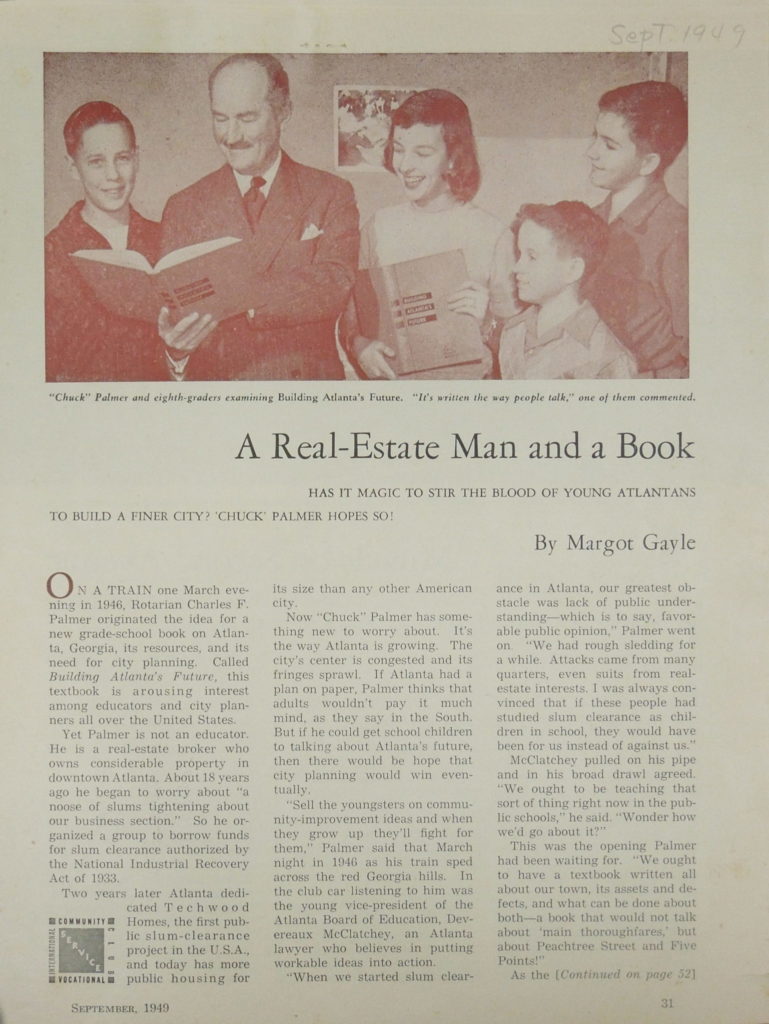

Atlanta’s first urban planning curriculum was developed in the late 1940s and the centerpiece of the program – the textbook Building Atlanta’s Future – awaited each eighth-grade student on their desk when they entered civics class in September 1948. The textbook, featuring an outline of the city of Atlanta on its cover, was richly illustrated and included accessible text that one student described as being “written the way people talk.”5 The 305-page book was divided into four sections – “Raw Materials of Cities,” “Cities Serve People,” “Meeting Group Needs,” and “Guiding City Growth” – and further divided into a total of fourteen chapters that addressed topics ranging from Atlanta’s economy to the organization of the city’s government. Importantly, as indicated by its title, the textbook did not seek to capture the city in a static state; rather, as the Atlanta Constitution suggested, it portrayed the:

. . . ideal Atlanta of the future, the city which can be developed through the proper planning that can come only as a result of knowing the factors which make up the city of today.6

And while the textbook was didactic, it was, more importantly, forward-looking; city leaders had ambitious plans for Atlanta’s future, and they knew execution of those plans would extend beyond their own tenure. Thus, they sought to capture the interest of children – the future leaders of the city – to assure that their visions for the city would be realized. As the textbook frames the issue for its young readers:

Today your parents are the workers, the citizens, the officials – the men and women carrying on where an older generation left off. Tomorrow it will be up to you. So, if you are planning to be alive five, ten, fifteen years from today, you should be interested in this. What kind of city would you like to live in then?7

In producing this textbook, Atlanta was participating in a post-war trend of integrating urban planning into civics curriculums. A 1948 study published in The School Review surveyed fifty-two public schools across the United States and found that thirty-one had a curriculum that included city planning education.8 The author of the study argued that city planning should not be reserved as a topic for graduate study but educators and city leaders should “look upon the public schools as the best vehicle for stimulating that support.”9

However, most schools lacked a comprehensive text to cover the topic. As revealed by the survey, schools relied on pamphlets and the annual reports of planning commissions. Likewise, an analysis of civics education published the year prior asserted that civics textbooks “limp far behind emerging problems in many instances, even on the basis of formal standards, of a generation ago, while emerging problems are often left out altogether.”10

Instead of adopting an outdated text or cobbling together various sources, neither of which would adequately serve their vision, city leaders called for the creation of Building Atlanta’s Future, a custom text. The textbook was seen as a long-term investment in cultivating support for Atlanta’s specific agenda. Moreover, education and civic leaders developed an innovative, pragmatic curriculum to complement the book and earned the city special acknowledgment in the article and recognition as a pioneer in urban planning education.11

As Atlanta was also a pioneer in public housing, it made sense that Building Atlanta’s Future would highlight that government program in particular. The city had been the first in the nation to build public housing, and accordingly, housing officials, planners, and reformers from other cities and countries often visited the city’s housing projects and sought the Atlanta Housing Authority’s (AHA) expert advice. Now, the publication of the textbook positioned the city as a pedagogical leader on the subject as well. More generally, Atlanta was the established capital of the “New South,” a distinction earned through considerable boosterism. Following the Confederacy’s defeat and the collapse of the plantation economy, future prosperity in the South required the establishment of a new industrial economy as well as a new public image. Henry Grady, editor of the Atlanta Constitution, was the most visible propagator of the “New South” philosophy writing numerous editorials and delivering speeches across the United States to promote the South as a place that possessed diversified agriculture, social stability, and moderate views on racial issues.12 A generation later, the Chamber of Commerce picked up the torch and organized the “Forward Atlanta” campaign from 1926 to 1929 in an effort to promote Atlanta as the South’s leading city to attract new factories and branch offices. Although part of the Jim Crow South, Atlanta was guided by the idea that good race relations were good for the city and prided itself on its interracial cooperation amongst white and African American leadership.13

In part, Building Atlanta’s Future was a continuation of the city’s boosterism as it sought to inspire pride in the city and investment from its youngest residents in its future growth. Thus, by giving public housing such a central role in this textbook, city leaders positioned that particular issue above many others as critical to Atlanta’s future success. In light of that, the book might also be understood as an extension of the AHA’s promotional work during its first decade of operation (1938–48), especially as it borrows heavily from the rhetorical and representational conventions used by the AHA in its annual reports. In those reports, as well as in the textbook, the housing program was presented as a means of providing shelter for low-income residents. Even more so, it was shown as a panacea for urban problems, a central element of comprehensive urban planning, and a critical component to the city’s overall economic success. Yet, the textbook adopted another convention from the AHA’s promotion of public housing – the erasure of race. In Building Atlanta’s Future, a book meant to speak to the city’s future leaders, the omission of African Americans from both the text and images sent a clear message about the vision for the city’s future leadership and raised questions about white leadership’s investment in interracial cooperation.

This exclusion from the book and planning process might be understood as a direct reaction to the increasingly formalized political power of Atlanta’s African American population. In 1946, two years before the book’s publication, the Georgia courts officially struck down the state’s white primary. African Americans now had increased political power and thus, the clout to demand more from the city. By 1949, this political shift would result in the formation of the oft-heralded “moderate coalition,” a progressive, biracial political alliance that would support economic growth, civic pride, and a moderate pace of racial change.14 While African Americans gained increasing political power in the city, their exclusion from Building Atlanta’s Future served as an indication that some were still reluctant to accept this new reality. For better or worse, Building Atlanta’s Future was successful in shaping a vision and trajectory for Atlanta. Even if the leaders of the current project have not indicated any knowledge of their historical predecessor, their new curriculum and Atlanta City Design grapples with the legacy it left and the consequences of the future it imagined. With insight into the history of urban planning curriculum in Atlanta, the current and future leaders of Atlanta will be better equipped to understand one of the sources that led to inequality’s continued hold on the city and the power that urban planning education can have on the city’s future.

Charles Palmer and the Composition of Building Atlanta’s Future

The idea for Building Atlanta’s Future had originated with Charles Palmer,15 a local real estate developer who had also submitted the funding applications for the first two public housing projects in Atlanta: Techwood Homes for white residents and University Homes for black residents. These two housing projects were not only the first to be constructed in Atlanta but also had the distinction of being the very first two Public Works Administration (PWA) projects in the United States.

As a Republican who had not voted for Franklin Roosevelt, Palmer was candid about his motivations for seeking federal funding for public housing. In a 1935 speech titled “World War Against the Slums,” Palmer stated:

One of the main thoroughfares, coming into the center of the district where our properties are, was lined by obsolete dwellings; a very bad district. The spread of that area was injuring our properties.16

While Palmer’s initial involvement in housing was directly related to his own financial interests, he would become deeply invested in the city’s public housing as well as the United States’ housing concerns, serving as the first chairman of the Atlanta Housing Authority’s (AHA) Board of Directors (1938–40) and then as defense housing coordinator in the Roosevelt administration (1940–41). As chairman of the AHA, Palmer developed a strategy for promoting public housing that was closely tied to Atlanta’s traditional boosterism.17 Building on the idea that Techwood Homes was good for his personal business and property values, he began promoting public housing not only as the best answer for providing safe and sanitary accommodations for low-income families but also as integral to assuring economic success for the entire city. Given the close ties between business interests and city hall during this period, the strategy was both popular and successful.

While Palmer exerted considerable influence over the content of the textbook, it was actually co-authored by John Ivey, Nicholas Demerath, and Woodrow Breland, all academics at the University of North Carolina,18 who organized an advisory committee, which included Palmer, in order to ensure that the textbook captured an accurate picture of Atlanta and included the appropriate content. Composed of approximately fifteen leading Atlanta citizens including the presidents of the Atlanta League of Women Voters, the Atlanta Teachers Association, and the Atlanta Rotary Club, as well as representatives of the business community and the Chamber of Commerce, the committee hoped to avoid the shortcomings of older civics textbooks via a focus on the current state of affairs in Atlanta, and inclusion of the city’s plans for the future.

“The Houses We Live In”

The authors of Building Atlanta’s Future framed the city’s existing eleven public housing projects not only as improved shelter but also as tools to control the spread of slums, improve property values, and decrease tax expenditures. In the chapter “The Houses We Live In,” Atlanta’s unique position in the nation’s public housing program was explained thus:

The Atlanta Housing Authority was one of the first in the country. Atlanta became a pioneer city in slum-clearance. Today it has more public housing than any city its size in this country. People come to Atlanta from other cities in America and as far away as New Zealand just to see our slum clearance projects.19

While the book touted the benefits of housing and clearly situated Atlanta as a pioneer, readers were reminded that to remain at the forefront of the housing movement, Atlanta needed to be “keeping eternally at it.”20 Across the country, public housing faced continued opposition with criticism coming from the private real estate industry as well as citizens who viewed the program as communist. For Atlanta to remain a leader, “keeping eternally at it” not only meant building more public housing but, perhaps more importantly, also building more support.21 Charles Palmer’s commitment to marketing Atlanta’s public housing program as well as his belief in the textbook as a medium for influencing the next generation of the city’s leaders were both evident in his insistence during the book’s composition that public housing be not only included, but prominently featured in Building Atlanta’s Future. For example, after reviewing a draft of the book’s outline, Palmer told the book’s main author, John Ivey, that he believed the project was off to a good start but warned that he planned to “plug for more prominence to be given housing, what it has done for Atlanta and what it can do for Atlanta than appears to be contemplated in your present outline.”22 Moreover, Palmer’s influence was apparent when the advisory committee later met to determine the book’s “points of emphasis and mode of presentation of content material” and decided “that the physical aspects of urban development [would] be a main focus of emphasis and that this [would] be brought out in as dramatic a way as practicable. Housing is to be recognized as an especially crucial problem in Atlanta.”23As he worked on the textbook, Palmer recollected that one of the greatest challenges in executing the PWA projects had been educating the community and fostering a positive view of public housing. As he explained:

When we started slum clearance in Atlanta, our greatest obstacle was lack of public understanding – which is to say, favorable public opinion. We had rough sledding for a while . . . I was always convinced that if these people had studied slum clearance as children in school, they would have been for us instead of against us.24

A similar sentiment was expressed in the textbook: “The people of Atlanta must help develop and must like a plan if it is to work.”25 Citizen support for public housing and urban planning were viewed as vital to the success of these programs, and Building Atlanta’s Future was thus seen as a tool to be used to gain the backing of students from a young age. As Palmer remarked:

. . . it is the youngsters of today who will guide the city tomorrow so the quicker we capture their interest the better the cities will become.26

The book was thus envisioned to both groom Atlanta’s future political and civic leaders as well as prime future voters to support the programs those leaders would hopefully direct.

In addition to being showcased in a dedicated chapter, public housing notably appeared throughout the textbook, supporting Palmer’s argument that public housing was an integral part of a better city and a benefit to all citizens. For example, in the chapter, “The Problems Atlanta Must Solve,” housing was presented as “perhaps Atlanta’s most obvious problem” and public housing was presented as the solution and “a step toward solving many other civic problems.”27 And in the chapter “Using Social Resources,” which addressed health issues, Palmer suggested the inclusion of information about public housing’s health clinics and outdoor playgrounds that contributed to a reduction in cases of tuberculosis.28

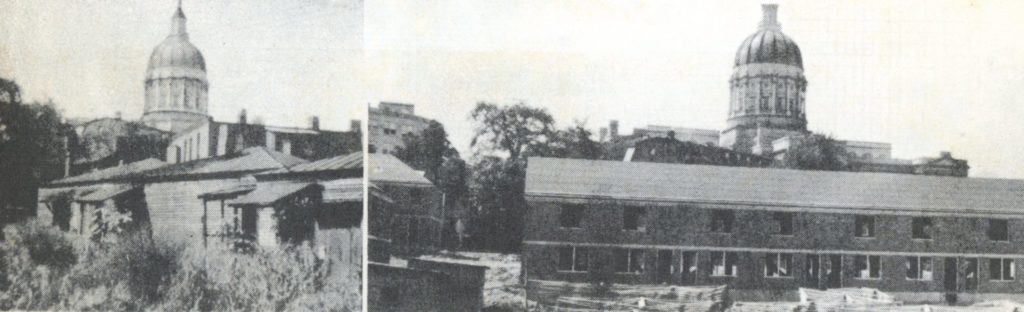

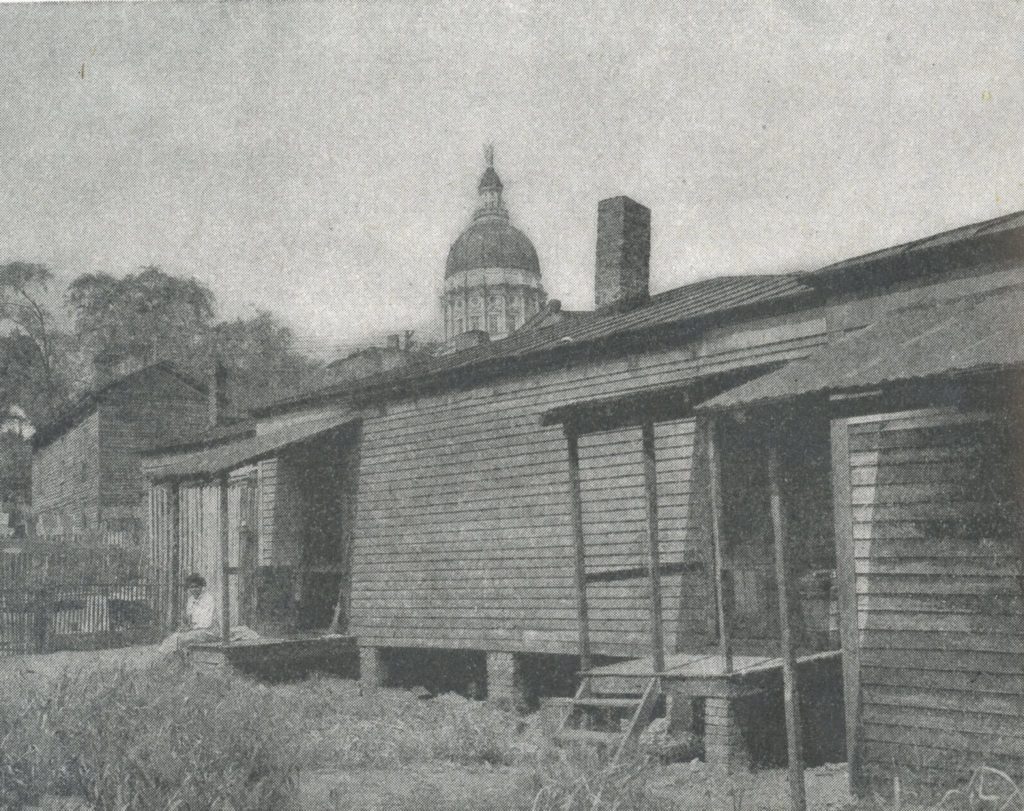

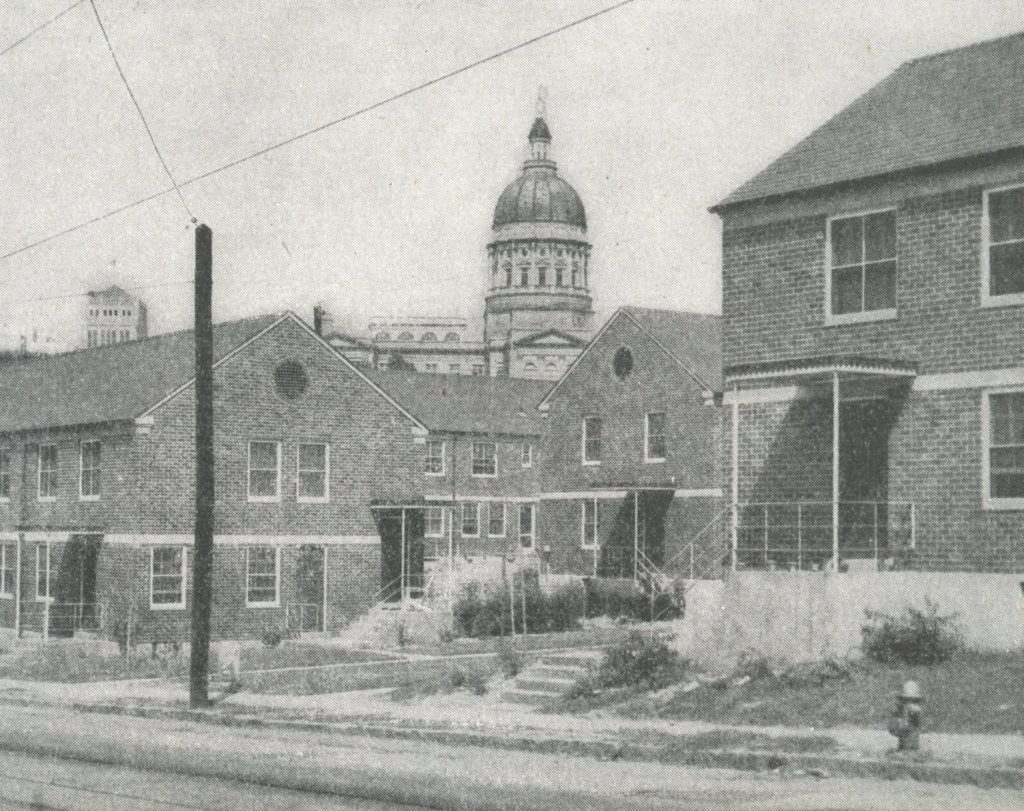

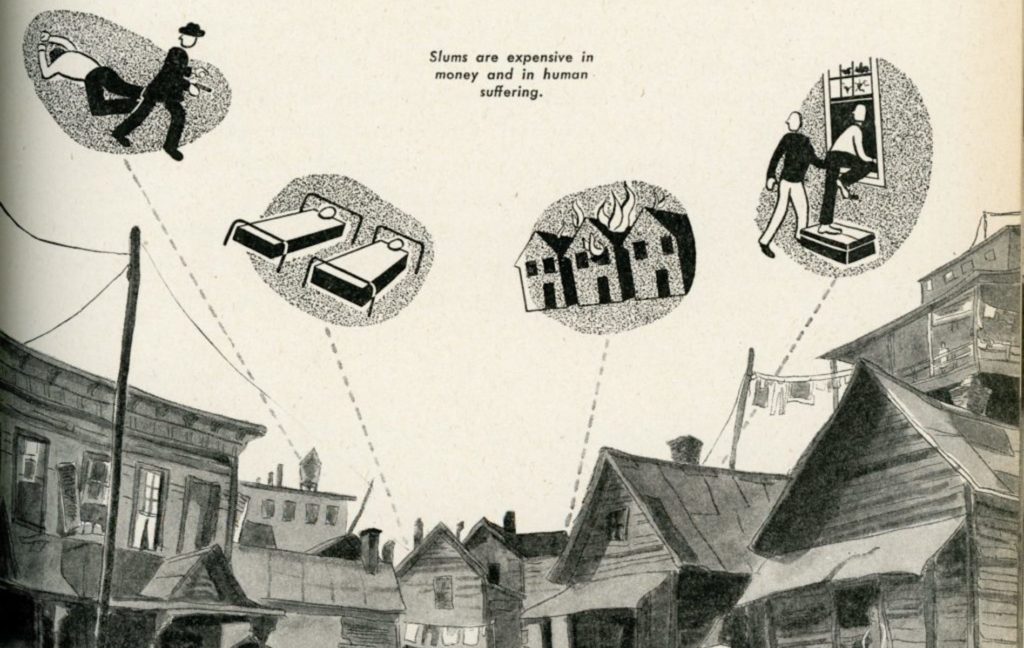

While giving careful consideration to the book’s text, Palmer and the advisory committee gave just as much attention to the overall design of Building Atlanta’s Future and to the inclusion of eye-catching images and graphs as is particularly clear in its coverage of housing. By the time the textbook was published, the Atlanta Housing Authority had published ten annual reports, and the influence of the rhetoric and visual conventions used in those annual reports can be seen throughout Building Atlanta’s Future. Both publications spoke about slums as breeders of disease and cancers in the city in addition to using “before and after” images to demonstrate the transformative power of public housing.

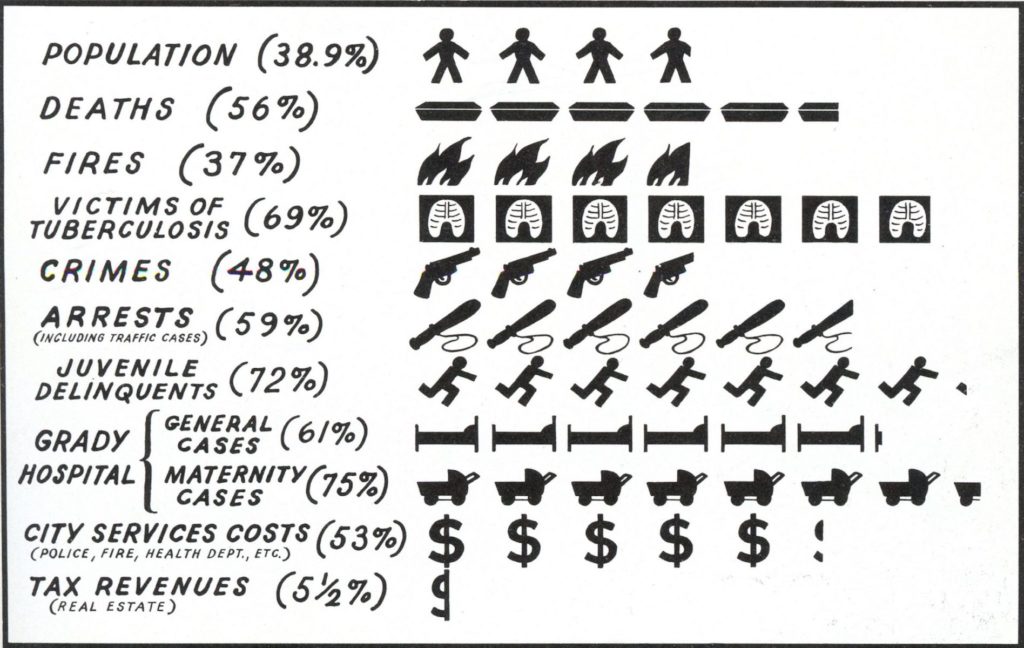

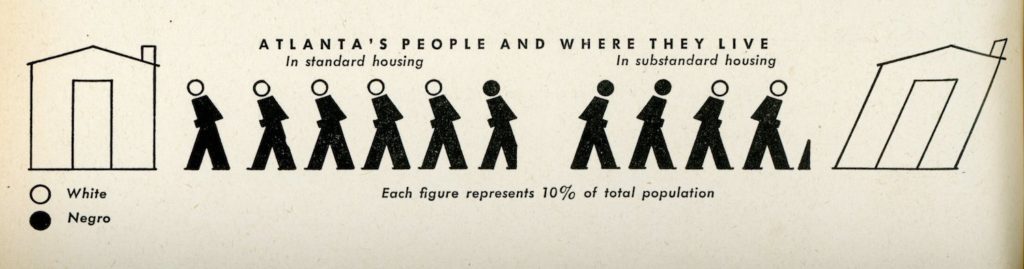

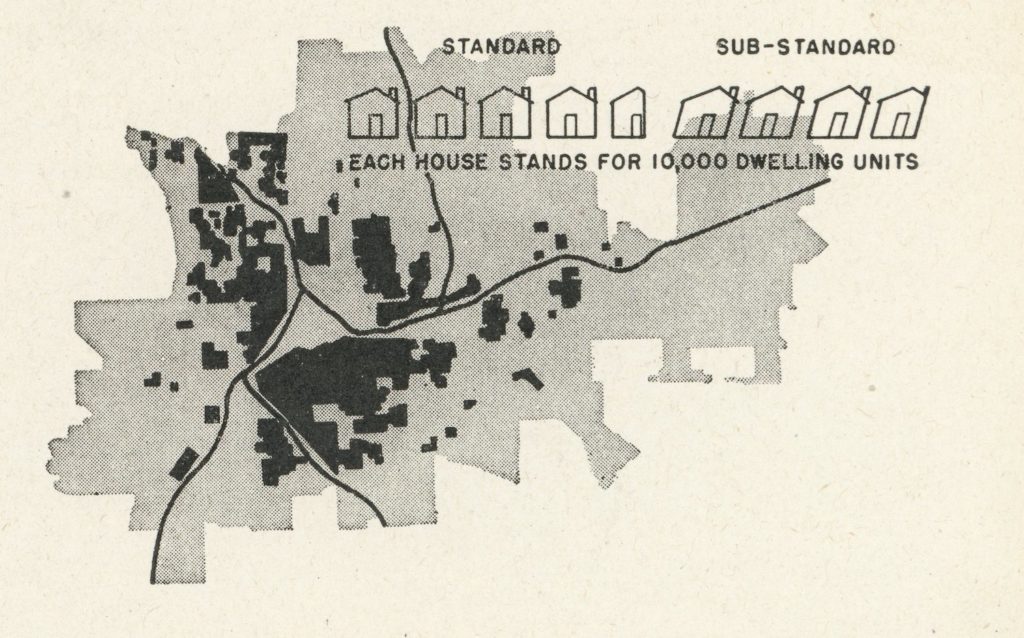

Simple “info graphics” were also widely used in both the book and the annual reports in order to offer a quick understanding of urban issues such as overcrowding, crime, and fire that were associated with the slums.

While the book received considerable praise for its presentation of public housing, there were also criticisms. In a letter to all PTA Presidents in the Atlanta metro area, E. W. Hiles, executive vice president of the Georgia Savings and Loan League, cautioned parents against Building Atlanta’s Future, especially the portions which addressed public housing. Hiles wrote:29

In chapter 9, of this text, the children in our schools are being taught that the primary responsibility for providing shelter for the people of this country rests upon the shoulders of the Government. Certainly this is contrary to all of the teachings and the experiences which you and I have undergone for as far back as we can remember.

Citing Palmer specifically and his involvement with the public housing program, Hiles also claimed: “Many of the statements made with reference to public housing projects in the Atlanta Area are deliberate attempts to sell the future men and women of this city on the Socialistic housing idea.”30 Finally, Hiles even suggested that the textbook was “part of a well-planned and well organized ‘softening up’ process, whereby the younger generation is expected to eventually come to accept the paternalistic idea in Government as the American Way of life.”31 Palmer would agree that the textbook was meant to accomplish exactly what Hiles feared it would – the acceptance of government housing as part of the city’s landscape and central to future plans for the city.

“I don’t think they had enough about the Negro’s progress in there”

Yet, for all of the innovation Building Atlanta’s Future promised, the textbook had a conspicuous defect: the almost total omission of African Americans. While priding itself on its moderate racial views, Atlanta was far from being a place of racial equality in 1948, as is reflected in the texbook’s matter-of-fact description of the city’s black and white populations as “two major physically different groups” and the claim that “We have built a great many of our customs around this difference.”32

In truth, these “customs” the text refers to were Atlanta’s segregated schools, neighborhoods, and employment, and the presence of these separate spaces was written about as an immutable feature of the city. Further, the few explicit references to the city’s “Negro population,” which comprised one-third of Atlanta’s population in 1948, offered no substantive discussion of how issues such as slum clearance and public housing, so central in the book, disproportionately impacted the African American community. In addition, African Americans appear in only a handful of the book’s numerous illustrations and photographs, and when they do, as I will explain later, their appearances were problematic. Finally, this exclusion is all the more notable given the increasing political clout of African American voters and the movement towards formalizing interracial cooperation in Atlanta politics.

The exclusion began when no African Americans were invited to serve on the advisory committee. During the formation of the committee, Ivey asked Palmer, “Did you take any further steps for the selection of Negro representatives?”33 In response to which, Palmer wrote: “No, nothing has been done about adding a Negro to the Advisory Committee because you will recall Miss Jarrell felt it too early in the study to handle either that phase or the labor phase of the matter now.”34 Palmer’s dismissal of Ivey’s inquiry indicates that he did not place importance on the inclusion of African Americans in planning the textbook, but rather saw racial issues as a secondary matter at best.

When one considers that public housing was emphasized throughout the textbook, and the fact that “a greater proportion of Negros than whites are badly housed,” was recognized in both the text and through infographics, the near erasure of African Americans in the book is even more glaring and problematic.35. At the time the textbook was written, 2,965 units of public housing existed for African Americans and 1,934 units existed for white residents. In the decade following the book’s publication, the Housing Act of 1949 would provide funding for an additional 1,990 units of African American public housing and 510 units of housing for whites in Atlanta by the mid-1950s.36 Public housing development as well as other urban planning programs, such as the 1946 Lochner Plan, which outlined the original freeway plan for the city, ultimately had a disproportionate impact on Atlanta’s African American population and thus writing about such programs with no input from or representation of the African American community was a flawed strategy.37

African American students, who were attending segregated schools and living in segregated neighborhoods or public housing projects, would have been hard pressed to see themselves as the future leaders of Atlanta when they did not even see themselves pictured as residents in the text. In fact, the only images they would have seen of African Americans in Building Atlanta’s Future were of movers, garbage collectors, or waiters, all service positions as opposed to leadership roles. To add insult to injury, the text mentioned that although African Americans were one-third of the city’s population, they did not contribute one-third of Atlanta’s total income because they “work at jobs that do not generally pay the highest wages.” The text went on to state, “In looking toward the future of Atlanta, we must think of the education, health, welfare and general security of the whole population. The needs of both races must be considered and encouraged to make the fullest contribution.”38

African Americans were essentially being accused of not contributing their fair share to the city. And yet, the very image and ideas promoted by Building Atlanta’s Future made future financial and civic contribution more difficult. But if there was opposition within the African American community to either the textbook’s representations or exclusion from the Advisory Committee, no records of this disapproval can be found.Exclusion from the textbook’s development explains, in part, the omission of African Americans from the pages of the text. However, Building Atlanta’s Future also followed a precedent set by the AHA’s annual reports in which African Americans were excluded from positive public housing images as a calculated way to promote public housing to white readers.

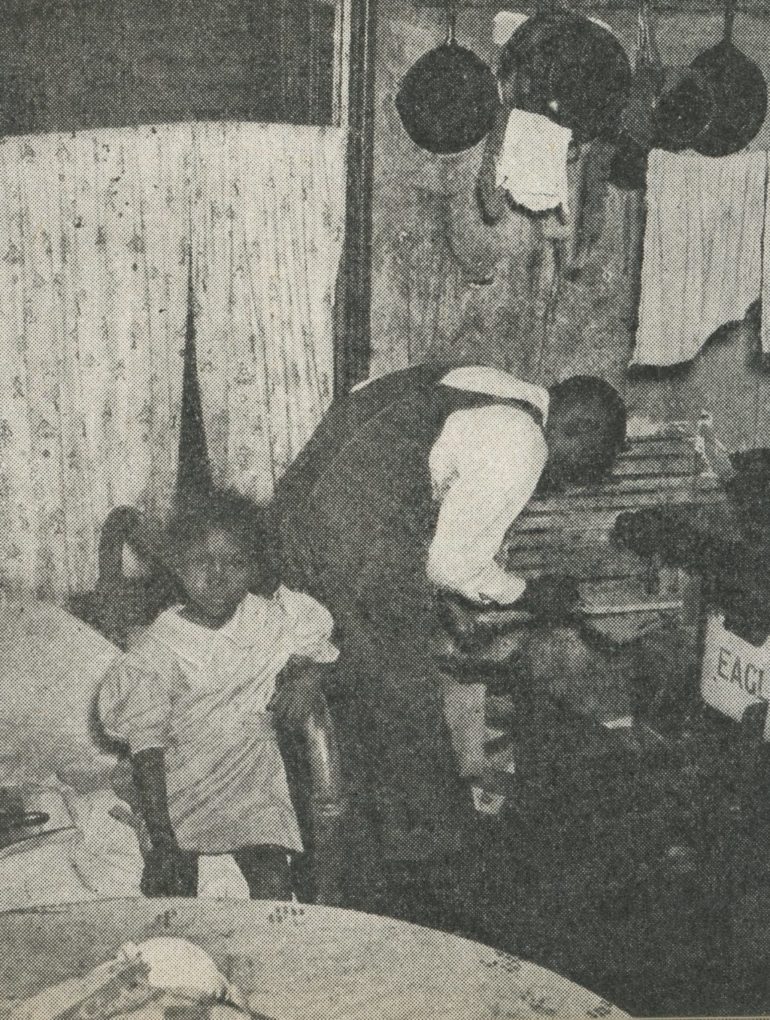

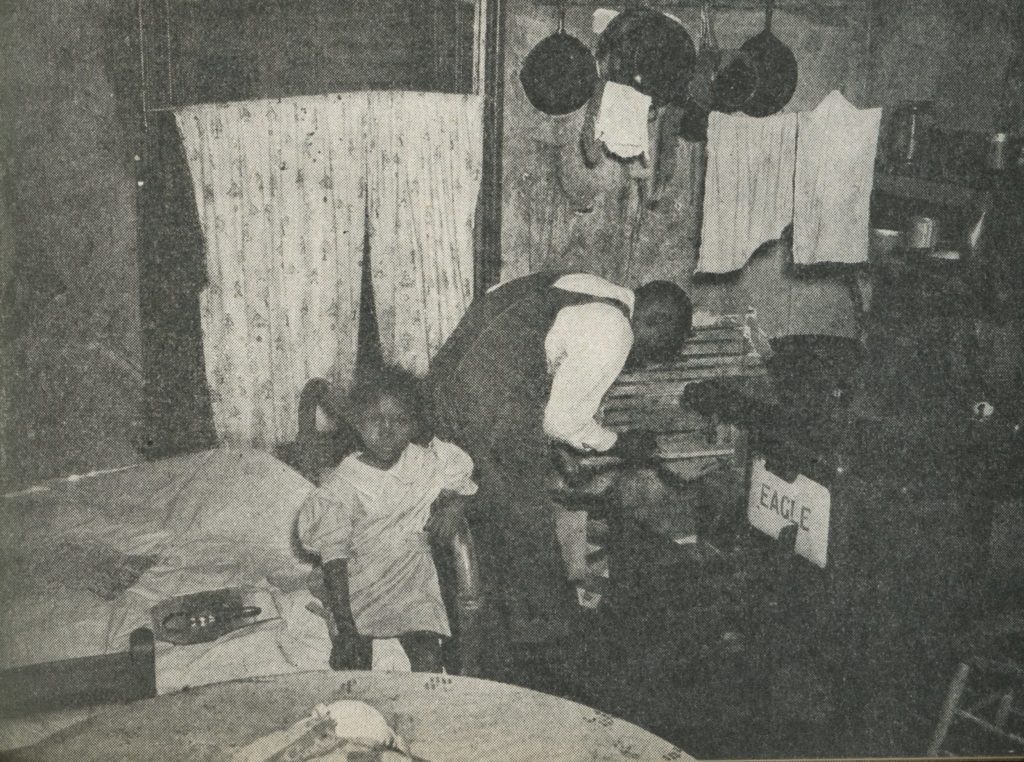

Although Atlanta built more housing projects for African Americans, early public relations work done by the AHA established public housing as a white space in the public imaginary in order to make support from white middle-class citizens more likely. Thus, the first eight annual reports published by the AHA did not show African Americans in public housing but only depicted them in slum housing. Public housing projects had been strategically placed to codify segregation and exclude African Americans from particular parts of the city and the public housing projects would remain segregated by race until the late 1960s.39

The visual segregation presented in the AHA’s promotional materials ultimately supported physical segregation by allowing the public to see it as reality in their mind’s eye. In the annual report images, blacks were continually visually connected to slums and slum conditions; meanwhile, whites were associated with clean, new, progressive public housing. Building on this convention, Building Atlanta’s Future similarly associated only whites with “Atlanta’s future.” Accordingly, one of the few photographic representations of African Americans in the textbook – which notably also appeared in the AHA’s First Annual Report – shows an African American family living in “poor housing,” and is meant to visualize the pre–public housing slums.

The all-white composition of the advisory board and the lack of representation of African Americans in the book itself is even more significant considering the political moment in Atlanta during which the book was composed and published. With the dissolution of the all-white primary in 1946, and a subsequent mass voter registration drive, African Americans in Atlanta had gained considerable political power, and would now be part of negotiating “a system of biracial agreements that lasted until the student-led protests in the early 1960s,” as noted by Clarence N. Stone.40 When the 1946 primary took place, 21,000 of the city’s 70,000 registered voters were African Americans, making the black vote an integral component of a candidate’s ability to get elected to office, which mayor William B. Hartsfield first took advantage of when African Americans helped him narrowly avoid a loss to challenger Charlie Brown in 1949.41 With this new political power, Atlanta’s African Americans were positioned to demand more from the city. Yet, while the civic involvement of African Americans became increasingly more official, their simultaneous exclusion from the imagined future of the city in Building Atlanta’s Future can be viewed as an example of a symbolic backlash and the unwillingness by white leaders to acquiesce to their new electoral and political power.

That is, in the text Palmer and the other leaders associated with the project effectively sent the message that they still envisioned the future of Atlanta’s political and civic power would remain exclusively white. While white residents were being sold a particular idea about the racial composition of Atlanta’s public housing, both black and white students met the exclusion of African Americans from Building Atlanta’s Future with criticism. In replying to a questionnaire about the book, an eighth-grade student from one of Atlanta’s two African American junior high schools wrote:42Meanwhile, students in the six white junior high schools also noted the absence and one commented: “The thing I didn’t like so much about this book was that it was all white and no Negro,” while another noted, “the book is all about white people, and colored people live here too.”43

Lessons from Atlanta’s Future

Atlanta was not only a pioneer in the creation of a new textbook and curriculum, but the city demonstrated that it was an innovator in promoting both and assuring that the book had a big impact. Though written for students and designed to influence young minds, the hope was that Building Atlanta’s Future would have a broader sphere of influence. Palmer stated: “The book itself we believe will be read by many of the parents of the children who take it home for study. In fact, it is designed with that in mind.”44 Yet, it ultimately had an even wider reach, as leaders and educators from other cities across the country inquired how Atlanta had developed the textbook and how their cities might do the same. In a letter to Charles Palmer, Ira Jarrell gave statistics about the interest that had been shown in Building Atlanta’s Future. While Jarrell indicated they hadn’t kept track of requests for the book that were made by phone or in person, forty-two requests were received as of October 26, 1949. Inquiries had come from 19 states, and Jarrell detailed that requests for information and copies of the book had come from public schools, universities, newspapers, writers’ clubs, librarians, city officials, city and county planning boards, research directors, as well as from interested individuals.45

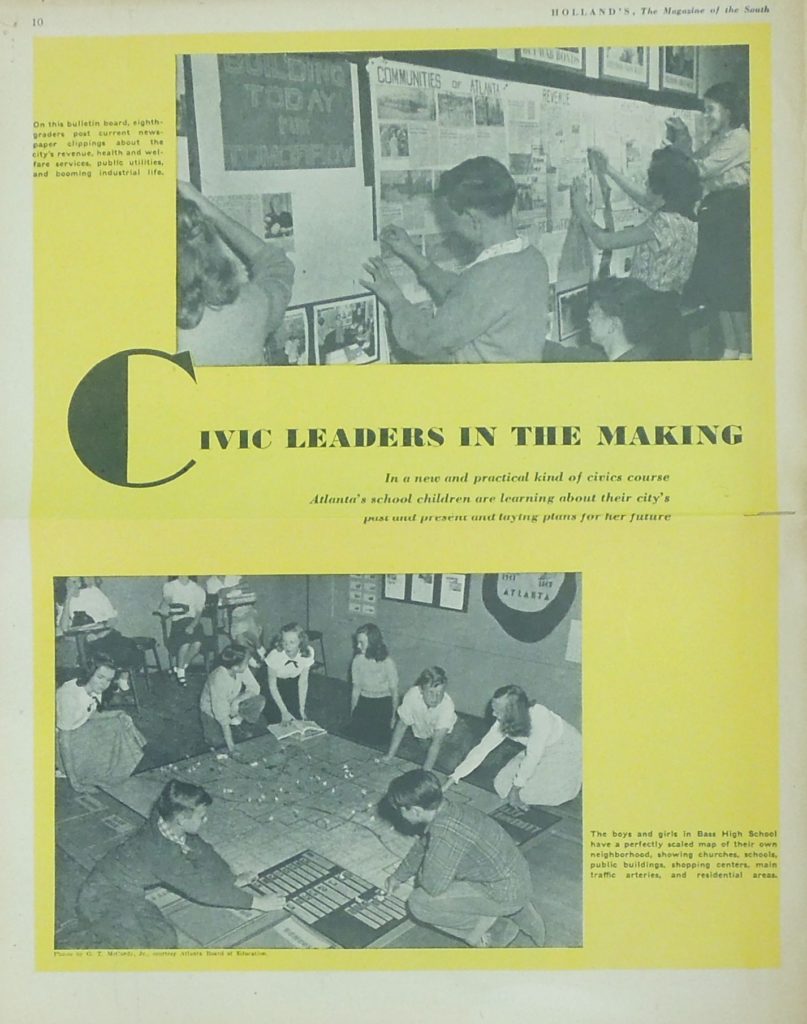

Palmer also compiled a list of people from whom he had received comments about the book. The list included the chairman of the BBC, Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, senators, the president of Harvard University, Leon Keyserling, who had been involved in New Deal housing programs, and members of planning committees and organizations across the United States. The book was also featured by journalist Margot Gayle in articles published in The Rotarian and Holland Magazine and even by Eleanor Roosevelt in her nationally syndicated column, “My Day” (Figure 10). And with the exception of the criticisms from Hiles, if there was negative press about the book, Palmer did not include it in his records.

Though written for students and designed to influence young minds, the hope was that Building Atlanta’s Future would ultimately have an even broader sphere of influence. Palmer stated: “The book itself we believe will be read by many of the parents of the children who take it home for study. In fact, it is designed with that in mind.”46

Yet, it ultimately had an even wider reach, as leaders and educators from other cities across the country inquired how Atlanta had developed the textbook and how their cities might do the same. In a letter to Charles Palmer, Ira Jarrell gave statistics about the interest that had been shown in Building Atlanta’s Future. While Jarrell indicated they hadn’t kept track of requests for the book that were made by phone or in person, forty-two requests were received as of October 26, 1949. Inquiries had come from nineteen states, and Jarrell detailed that requests for information and copies of the book had come from public schools, universities, newspapers, writers’ clubs, librarians, city officials, city and county planning boards, research directors, as well as from interested individuals.47

Palmer also compiled a list of people from whom he had received comments about the book. The list included the chairman of the BBC, Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter, senators, the president of Harvard University, Leon Keyserling, who had been involved in New Deal housing programs, and members of planning committees and organizations across the United States. The book was also featured by journalist Margot Gayle in articles published in The Rotarian and Holland’s Magazine and even by Eleanor Roosevelt in her nationally syndicated column, “My Day”48

And with the exception of the criticisms from Hiles, if there was negative press about the book, Palmer did not include it in his records. Certainly, Building Atlanta’s Future provided the city’s students with pragmatic plans for building the city’s physical features. However, the symbolic aspects of building the city’s future and who was and was not included needs to be recognized as an equally, if not more so, influential dimension of the text. In a moment when African Americans were securing expanded rights and political power, their exclusion from the textbook and from Atlanta’s imagined future sent a powerful message that there was resistance to this new reality.

Within the book, Palmer made certain that public housing was positioned as an integral part of city planning, central to assuring economic success for the entire city, and the best answer for providing safe and sanitary accommodations for low-income families. However, given that no African Americans were shown living in public housing, Building Atlanta’s Future demonstrates that the real value Palmer saw in public housing was its benefit to white property owners and taxpayers. Improved shelter for African Americans was secondary.As Atlanta is poised to begin its latest endeavor in civics and urban planning education, it is critical that we understand and learn from the city’s historical endeavors in this field to avoid repeating the same mistakes.

While there are many parallels between the newly proposed curriculum based on Atlanta City Design and the 1948 curriculum based on Building Atlanta’s Future, there are striking differences. Both texts and curriculums support the idea that children – the city’s future leaders and residents – need to learn about the importance of urban planning and that gaining their support is integral for the fruition of their vision and future success of Atlanta. However, where Building Atlanta’s Future was exclusionary in its text, images, and the planning process behind it, Atlanta City Design explicitly focuses on diversity, inclusivity, accessible transportation, and affordable housing. With chapters titled “Equity,” “Let’s Include Everyone,” and “Let’s Prioritize People,” and pages filled with images of a city populated by people of many races, the new book is a clear departure from the earlier text. For example, the illustration in Atlanta City Design of a now-demolished public housing building is captioned, “Recognize and Rebalance historic injustice.”49 By indoctrinating future leaders in a vision for the city that did not include one-third of the population in any meaningful way, Building Atlanta’s Future was in part responsible for creating and perpetuating such an “historic injustice” as destroying public housing. In contrast, this new curriculum and the text it is built around are both positive steps towards recognizing and rebalancing this and other historic injustices from Atlanta’s past so that its future might be different.

Citation: Schank, Katie Marages. “Learning our Lessons: Civics Education, Urban Planning, and Race in Postwar Atlanta.” Atlanta Studies. May 31, 2018. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20180531.

Katie Marages Schank is an independent scholar. She received her PhD in American Studies from George Washington University and from 2016 to 2017 was a fellow at Emory University’s James Weldon Johnson Institute. She is currently working on a manuscript about the important role of promotion and representation in the history of Atlanta’s public housing.

Notes

- City of Atlanta Department of City Planning, Atlanta City Design: Aspiring to the Beloved Community (Atlanta, GA: City of Atlanta Department of City Planning, 2017), http://atlcitydesign.com/acd_book.html. The authors of the document state: “The Atlanta City Design: Aspiring to the Beloved Community is a guiding document for the City of Atlanta. Its purpose is to articulate an aspiration for the future city that Atlantans can fall in love with, knowing that if people love their city, they will make better decisions about it. These decisions, then, will be reflected in all the plans, policies, and investments the city makes, allowing Dr. King’s concept of the Beloved Community to guide growth and transform Atlanta into the best possible version of itself.” The guide will eventually be published as a book, but can currently be viewed in its entirety at atlcitydesign.com.[↩]

- In 2015, Gabrielle Lyon, of the Chicago Architecture Foundation, began teaching high school students urban planning using the 1911 Wacker’s Manual, a textbook based on Daniel Burnham’s 1909 plan of Chicago. Responding to students’ requests for a book that addressed more contemporary issues, Lyon created No Small Plans, a three-volume graphic novel that examines historical, present-day, and future planning in Chicago. See: Mimi Kirk, “Drawing Up an Urban Planning Manual for Chicago Teens, CityLab, April 5, 2017, https://www.citylab.com/life/2017/04/chicago-architecture-foundation-no-small-plans-graphic-novel-teens/521802/.[↩]

- “APS Partners with City of Atlanta to Create Enhanced Social Studies Curriculum Inspired by Atlanta City Design,” Talk Up APS: The Official Blog of Atlanta Public Schools, December 22, 2017, https://talkupaps.wordpress.com/2017/12/22/aps-partners-with-city-of-atlanta-to-offer-an-enhanced-social-studies-curriculum-inspired-by-atlanta-city-design/.[↩]

- Atlanta City Design, 5.[↩]

- Margot Gayle, “A Real-Estate Man and a Book,” The Rotarian 75, no. 3 (September 1949): 52.[↩]

- “‘Building Atlanta’s Future’ Guide to City Development,” Atlanta Constitution, September 12, 1948, 12C.[↩]

- Ivey, Demerath, and Wilson, Building Atlanta’s Future, 10.[↩]

- James F. Short Jr., “City Planning in Public Schools: A Survey,” The School Review 59, no. 5 (May 1951): 291.[↩]

- Ibid, 296.[↩]

- Charles E. Merriam, “Civic Education in the United States,” The Journal of General Education 1, no. 4 (July 1947): 262.[↩]

- Surging Cities, the textbook developed for Boston schools, was also featured for its inclusion of region-specific information in the first half of its text. While Buffalo, Detroit, and Los Angeles had also developed textbooks for classroom use, the content of their textbooks was not city-specific.[↩]

- Henry Woodfin Grady, The New South: Writings and Speeches of Henry Grady (Savannah, GA: Beehive Press, 1971).[↩]

- For readings on race, politics, and Atlanta, see: Ronald Bayor, Race and the Shaping of Twentieth-Century Atlanta (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996); Tomiko Brown-Nagin, Courage to Dissent: Atlanta and the Long History of the Civil Rights Movement (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011); Karen Ferguson, Black Politics in New Deal Atlanta (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2002), Kevin Kruse, White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007); and Clarence Stone, Regime Politics: Governing Atlanta, 1946–1988 (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1989).[↩]

- See Kruse, White Flight, 31–41.[↩]

- Charles Palmer cited the 1911 Wacker’s Manual of the Plan for Chicago as his inspiration for Building Atlanta’s Future. Wacker’s Manual had been published to teach school children about Daniel Burnham’s Chicago Plan and urban planning with the belief that educating children in regard to their future responsibilities was the solution to the major problems in American cities. For more on urban planning education for children see Thomas J. Sclereth, “Burnham’s Plan and Moody’s Manual: City Planning as Progressive Reform,” Journal of the American Planning Association 47 (1918): 72.[↩]

- Charles F. Palmer, “The World War Against the Slums” (speech delivered at the Twenty-Eighth Annual Convention of the National Association of Building Owners and Managers, Cincinnati, Ohio, June 10–13, 1935), Box 154, Charles Forest Palmer Papers, Rose Library, Emory University. (Henceforth CFP and Rose Library.) More on Charles Palmer’s life and work can be found in his autobiography Adventures of a Slum Fighter (Atlanta: Tupper and Love, 1955).[↩]

- The promotion strategies used by Palmer can be traced to the Chamber of Commerce’s “Forward Atlanta” campaign, first executed from 1926-1929. The campaign was designed to further boost Atlanta’s reputation as the South’s leading city and to “advertise” and “sell” the city as an ideal location for new factories and branch offices, much in the way that a company would sell a consumer product. See also Charles Rutheiser, Imagineering Atlanta: The Politics of Place in the City of Dreams (New York: Verso Books, 1996).[↩]

- All three authors were faculty members at the University of North Carolina and members of the university’s Division of Research Interpretation Institute for Research in Social Science. Demerath had formerly been housing economist and director of research and planning at the National Housing Agency. He also served as an advisor to the president of the Philippines on urban rehabilitation, and had been a member of the faculties of Tulane and Harvard Universities.[↩]

- Ivey, Demerath, and Wilson, Building Atlanta’s Future, 168.[↩]

- Ibid, 171.[↩]

- For information regarding the challenges public housing in the United States faced during this era, see D. Bradford Hunt, “How Did Public Housing Survive the 1950s?” Journal of Policy History 17, no. 2 (2005): 193–216.[↩]

- Letter, Palmer to Ivey, May 3, 1946, box 13, folder 1, CFP, Rose Library.[↩]

- Report of Project Activities, January to July 1947, John E. Ivey, Jr. to the Atlanta Textbook Advisory Committee, July 11, 1947, box 13, folder 1, CFP, Rose Library.[↩]

- Gayle, “A Real-Estate Man and a Book,” 31.[↩]

- John E. Ivey, Jr., Nicholas J. Demerath, and Woodrow W. Breland, Building Atlanta’s Future (Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1948): 276.[↩]

- Letter, Charles Palmer to Harlean James, January 26, 1949, box 13, folder 1, CFP, Rose Library.[↩]

- Ibid, 266.[↩]

- Letter, Charles Palmer to Woodrow Breland, December 17, 1947, box 13, folder 1, CFP, Rose Library.[↩]

- Letter, E.W. Hiles to PTA Presidents in the Atlanta metropolitan area, June 8, 1949, box 13, folder 2, CFP, Rose Library.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- Ivey, Demerath, and Wilson, Building Atlanta’s Future, 75.[↩]

- Letter, John E. Ivey, Jr. to Charles Palmer, August 23, 1946, box 13, folder 1, CFP, Rose Library.[↩]

- Letter, Charles Palmer to John E. Ivey, August 27, 1946, box 13, folder 1, CFP, Rose Library.[↩]

- Ivey, Demerath, and Wilson, Building Atlanta’s Future, 165.[↩]

- Public Housing statistics provided by the Atlanta Housing Authority.[↩]

- While known as the Lochner Plan for its author Harry W. Lochner, its official title was The Highway and Transportation Plan.[↩]

- Ivey, Demerath, and Wilson, Building Atlanta’s Future, 85. The uneven financial contribution and fact that Atlanta’s African Americans were relegated to service positions is highlighted on page 263 as one of “The Problems that Atlanta Must Solve.”[↩]

- For an examination of segregation as related to housing practices see: Bayor, Race and the Shaping of Twentieth Century Atlanta; Ferguson, Black Politics in New Deal Atlanta; Lee Ann Lands, Culture of Property: Race, Class, and Housing Landscapes in Atlanta, 1880–1950 (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2009); Matthew Lassiter, The Silent Majority: Suburban Politics in the Sunbelt South (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005); and Lawrence J. Vale, Purging the Poorest: Public Housing and the Design Politics of Twice-Cleared Communities (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2013).[↩]

- Stone, Regime Politics, 26; see also chapter 3.[↩]

- Ibid., 30.[↩]

- Gayle, “A Real-estate man and His Book,” 53.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- Letter, Charles Palmer to G. Harvey Porter, April 1, 1948, box 13, folder 1, CFP, Rose Library.[↩]

- Letter, Ira Jarrell to Charles Palmer, October 26, 1949, box 13, folder 3, CFP, Rose Library.[↩]

- Letter, Charles Palmer to G. Harvey Porter, April 1, 1948, box 13, folder 1, CFP, Rose Library.[↩]

- Letter, Ira Jarrell to Charles Palmer, October 26, 1949, box 13, folder 3, CFP, Rose Library.[↩]

- Gayle, “A Real-Estate Man and a Book”; Margot Gayle, “Civic Leaders in the Making,” Holland’s: The Magazine of the South, December 1949, 10–14; Eleanor Roosevelt, “My Day,” January 20, 1949, https://www2.gwu.edu/~erpapers/myday/displaydoc.cfm?_y=1949&_f=md001181.[↩]

- Atlanta City Design, 151.[↩]