On March 19, 2019, Gwinnett County voters went to the polls to reject MARTA membership for the third time since 1971.

With ongoing demographic shifts, worsening transportation conditions, and helpful state legislation, supporters were hopeful that the measure would pass. One such change in state law took place in May 2018, when Governor Nathan Deal signed House Bill (HB) 930 into law. The new law upends decades of Georgia transportation policy by, among other things, making some state funding available for public transit operations and lowering the bar for thirteen counties in the Atlanta metro region to fund public transit through local sales taxes. The new law also forces a rebranding of public transit in the region. While current transit systems will continue to exist, the look and feel of buses and trains is already changing. By 2023, they will all sport new signage referring to The Atlanta-region Transit Link Authority (“The ATL”).

This new agency will also create a regional plan for public transit, holding out the promise of a truly integrated system coordinated across city and county boundaries. Integrated planning across the region would recognize that hypothetical new service in Marietta would benefit others commuting into the city of Atlanta by providing alternatives to a congested commute on I-75. The best transportation improvements should deliver benefits widely across the region; whether they are physically located in a particular jurisdiction is of secondary importance since the lion’s share of trips cross many jurisdictions. You could be forgiven for thinking that we’ve been here before. The Georgia Regional Transportation Authority (GRTA) was created in the wake of Atlanta’s well-publicized “conformity lapse” when the region failed to meet federal air quality standards and transportation funding was threatened.1 In many ways, HB 930 responds to the earlier experience with GRTA during the late 1990s and early 2000s. GRTA’s founding law endowed it with great authority – to approve or deny projects judged to be inconsistent with regional goals. But this authority struck fear into the hearts of city and county decision makers. They bristle when their local autonomy is threatened by higher levels of government. Additionally, regional authority is often viewed as illegitimate as those serving on regional boards are typically appointed and drawn from local government posts rather than being elected to serve a regional constituency.

The need for a regional transit authority is also complicated because we already have a regional transit provider in metropolitan Atlanta that has been operating transit service since the early 1970s – the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority, or MARTA. Currently, MARTA operates in three counties: Fulton, DeKalb, and Clayton. It is one of the ten most patronized public transit systems in the country, responsible for a combined operating and capital budget annually of approximately $1 billion.2 During Keith Parker’s recent tenure as MARTA chief executive, the agency’s financial situation improved dramatically. When Parker stepped down in 2017, MARTA was consistently seeing a budget surplus, two sales tax measures had successfully passed, and the 2014 expansion of MARTA into Clayton county represented the first major change in the geography of MARTA since the system’s founding.3With MARTA well positioned to operate a multi-jurisdictional transit system, why isn’t it charged with undertaking regional transit integration under HB 930? The answer, like many issues in Atlanta history, has to do with race, and it’s helpful to look to the history to understand what’s going on today.4

Racialized Transportation History

The relationship between federal highway policy and white flight has been well documented.5 In short, the federal government raised gasoline taxes and created the Highway Trust Fund to bankroll the rapid construction of interstate freeways beginning in the mid-1950s. These freeways served dual purposes: allowing for “slum removal” and facilitating rapid transportation between central cities and suburbs. In the wake of the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, an anxious white population increasingly sought refuge in suburban areas where it could enact exclusionary housing policies and establish racially homogenous school districts. The primary beneficiaries of freeway construction were thus new white homeowners who could commute between city and suburb, while those who bore the brunt of the “removal” involved in freeway construction were black people and low-income people across the United States.

By the mid-1960s, the profoundly negative impacts of freeway construction on neighborhood cohesion were well known, and the nascent environmental movement began to question the wisdom of automobile dependence for its consumption of open space, air pollution, and effects on quality of life. “Freeway revolts” began to break out across the country and residents and decision makers sought alternatives to unbridled automobility.6

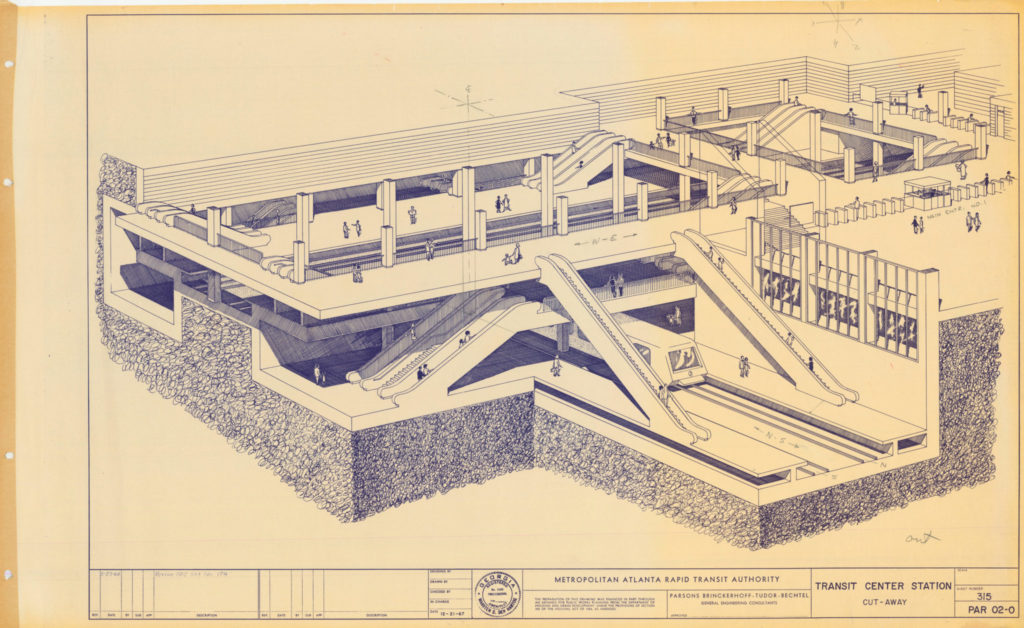

Accordingly, in 1961 the first rapid transit plan for Atlanta was released. The federal government made funding available for public transit in 1964, and in 1965 the MARTA Act passed. The act established a special transit district in Gwinnett, Fulton, DeKalb, and Clayton Counties. Cobb County voters did not approve the initial MARTA Act and were not part of the system. Then in 1971, the sales tax needed to fund the new system passed only in Fulton and DeKalb counties largely because of the support of black City of Atlanta voters.

MARTA’s initial promise was that it would be a five-county regional network. What happened? Three factors explain its limited initial reach.

First, a sizable automobile infrastructure had been created over the prior decade. The automobile was (and still is) viewed as the pinnacle of transportation technology. It had facilitated massive shifts in lifestyle, urban form, and economic prosperity. People liked (and still like) cars. Asking residents of outlying counties to pay additional funds for a completely new system was a heavy lift in this context.

Second, the immediate benefits to suburban jurisdictions of MARTA were perceived to be too small. Initial plans had few stations in suburban jurisdictions. Clayton County, for example, had only one rail station proposed. While this might have been viewed as the right thing to do from a transit planning perspective, it didn’t play well in the political sphere. MARTA opponents spoke of sales taxes being collected in the suburban jurisdictions being sent to benefit the City of Atlanta.

The third, and in my view most important reason, was racism. Gwinnett, Clayton, and Cobb were all about 95 percent white as of the 1970 US census. The City of Atlanta had been steadily losing white residents over the prior decades, dropping from 300,000 in 1960 to 140,000 in 1980. The suburban rejection of MARTA was a way to cement the separation between the black City of Atlanta and the white suburbs. Suburban residents who had just fled the city were very quickly being asked to connect to it through a new regional transit system – there was no way they would agree.Notably, this racialized view of MARTA has persisted until the present day. A New York Times story in the late-1980s reported on bumper stickers reading “Share Atlanta Crime – Support MARTA.”7 While there is no evidence that the expansion of public transit leads to increases in crime, these types of implicit associations between public transit, its users, crime, effects on property values, and the presence of affordable housing are a staple of opposition to public transit across the country. Given the initial racialized history of MARTA, such associations take on an especially pronounced racial dimension in the region. As a result, efforts to expand the system to Gwinnett and Cobb counties have repeatedly failed, including Gwinnett’s 2019 attempt.8

Why Rebrand MARTA?

HB 930’s proposal to “rebrand” the region’s public transit system cannot be understood separate from Atlanta’s racialized transit history. It is clearly an attempt to move beyond these prior associations. Prior to passage of HB 930, chairman of the MARTA board, Robbie Ashe acknowledged that “the MARTA name still has some historic baggage.”9 One of the bill’s sponsors, state Senator Brandon Beach stated simply that “a refresh [will] help and get people to be more accepting of regional transit.”10 For anyone familiar with the region’s legacy of segregation, racism, and transportation planning, the reason for the needed “refresh” is clear. But Atlanta metro residents should question whether HB 930’s creation of yet another layer of transportation bureaucracy is truly necessary. It might be more correctly viewed as a sort of “racial tax.” It is the price that residents of the region have to pay for a legacy of racialized and racist decisions about transportation and housing in the region. With public perceptions of MARTA clearly changing – Gwinnett’s March 2019 vote failed by a much slimmer margin than prior referenda in spite of familiar racialized opposition11 – the need for rebranding is far from obvious.12

It also sends a clear message to the region’s black residents: the transit system whose creation you supported and whose services you patronized over the past half century needs a new name now that suburbanites are interested in using it. I suspect and hope that this perception exists largely in the minds of decision makers rather than residents.

There will likely be many opportunities to course correct as HB 930 is implemented. But while there are certainly many positive elements embedded within it, “The ATL” is not one of them.

Citation: Karner, Alex. “MARTA Rebranding Rooted in a Racialized History of Public Transit.” Atlanta Studies, April 23, 2019, https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20190423.

Notes

- Arthur C. Nelson, “New Kid in Town: The Georgia Regional Transportation Authority and its Role in Managing Growth in Metropolitan Georgia,” Wake Forest Law Review 35, no. 3 (Fall 2000): 625–44; Miriam Konrad, Transporting Atlanta: The Mode of Mobility under Construction (Albany, NY: State University of New York Press, 2009).[↩]

- Dave Williams, “MARTA board OKs FY2018 Budgets,” Atlanta Business Chronicle, June 2, 2017, https://perma.cc/859L-V8ML.[↩]

- Alex Karner and Richard Duckworth, “’Pray for Transit’: Seeking Transportation Justice in Metropolitan Atlanta,” Urban Studies (August 2018), https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018779756.[↩]

- I’ve previously documented this history for the Atlanta metropolitan region in a report called “Opportunity Deferred.”[↩]

- Charles E. Connerly, “From Racial Zoning to Community Empowerment: The Interstate Highway System and the African American Community in Birmingham, Alabama,” Journal of Planning Education and Research 22, no. 2 (2002): 99–114, https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X02238441; Kevin Kruse, White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005).[↩]

- Raymond A. Mohl, “Stop the Road: Freeway Revolts in American Cities,” Journal of Urban History 30, no. 5 (2004): 674–706, https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144204265180.[↩]

- William E. Schmidt, “Racial Roadblock Seen in Atlanta Transit System,” New York Times, July 22, 1987, https://perma.cc/8BK9-4KVZ.[↩]

- Tyler Estep, “Bruising Lessons from Gwinnett’s 1990 MARTA Vote Linger Today,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, February 18, 2019, https://perma.cc/TC8C-33NA; Jason Henderson, “Secessionist Automobility: Racism, Anti-Urbanism, and the Politics of Automobility in Atlanta, Georgia,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 30, no. 2 (2006): 293–307, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2006.00662.x.[↩]

- Tasnim Shamma, “Chairman Says MARTA Is Open to Calling Itself ‘The ATL’,” WABE, February 6, 2018, https://perma.cc/998W-LXVW.[↩]

- Stephannie Stokes, “Lawmakers Look to Remake Image of Transit in Metro Atlanta,” WABE, June 7, 2018, https://perma.cc/S42K-QSZU.[↩]

- See Tyler Estep, “Gwinnett MARTA Election: How Important Is a Formal Opposition Effort?” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, March 7, 2019, https://perma.cc/85XH-YYMG; Tyler Estep and David Wickert, “Fears About MARTA in Suburbs Familiar but Changing” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, February 21, 2019, https://perma.cc/Y7XP-97ZK.[↩]

- Tyler Estep, “Gwinnett’s Monumental MARTA Vote Reflects Region’s Changing Attitudes,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, August 3, 2018, https://perma.cc/B3KA-QDWJ.[↩]