Cities are always changing.

Old streetscapes are effaced and redeveloped for new urban planning objectives. Or perhaps the buildings remain, but new residents and businesses replace their previous inhabitants. Either way, a space that served a particular function in one era will take on different meaning and purpose in another: an industrial district becomes a public park; an immigrant quarter becomes a highway interchange; a poor people’s neighborhood becomes a rich people’s neighborhood. But much like a textual palimpsest, where earlier writings remain visible just beneath the surface, a city’s previous forms and functions remain somehow spectrally present, even if only in memory or in stories handed down. As historian Timothy Crimmins noted in his 1982 essay “The Atlanta Palimpsest,” the “impress of each generation” is “imperfectly erased.”1

In the city, we are surrounded by histories rendered not quite invisible.“Streetscape Palimpsest: A History of Georgia Avenue” reveals and amplifies the nearly-silenced layers and voices of the past on one Atlanta street – one that is, at this very moment, undergoing massive redevelopment. Georgia Avenue’s history dates back to the 1870s; it runs east to west, bisecting both Summerhill and Grant Park, two of the oldest residential neighborhoods in the city. By focusing on the layers of history along this single Atlanta thoroughfare, “Streetscape Palimpsest” accounts for the sweeping, impersonal forces that shaped (and continue to reshape) so many American cities: racial segregation, immigrant acculturation, redlining, urban renewal, white flight, and the dubious reliance on sports facilities to stimulate local economies. At the same time, this project reminds us that the people of Georgia Avenue’s past were not passive victims, but active participants who, over the past century, sought to contain neighborhood change, to influence its direction, and to make it work for themselves and their communities. By adopting a fine-grained, street-level perspective, we can see how everyday individuals, in all their diversity and complexity, have helped to shape the history of our city.

The Rise and Fall (and Rise?) of Georgia Avenue

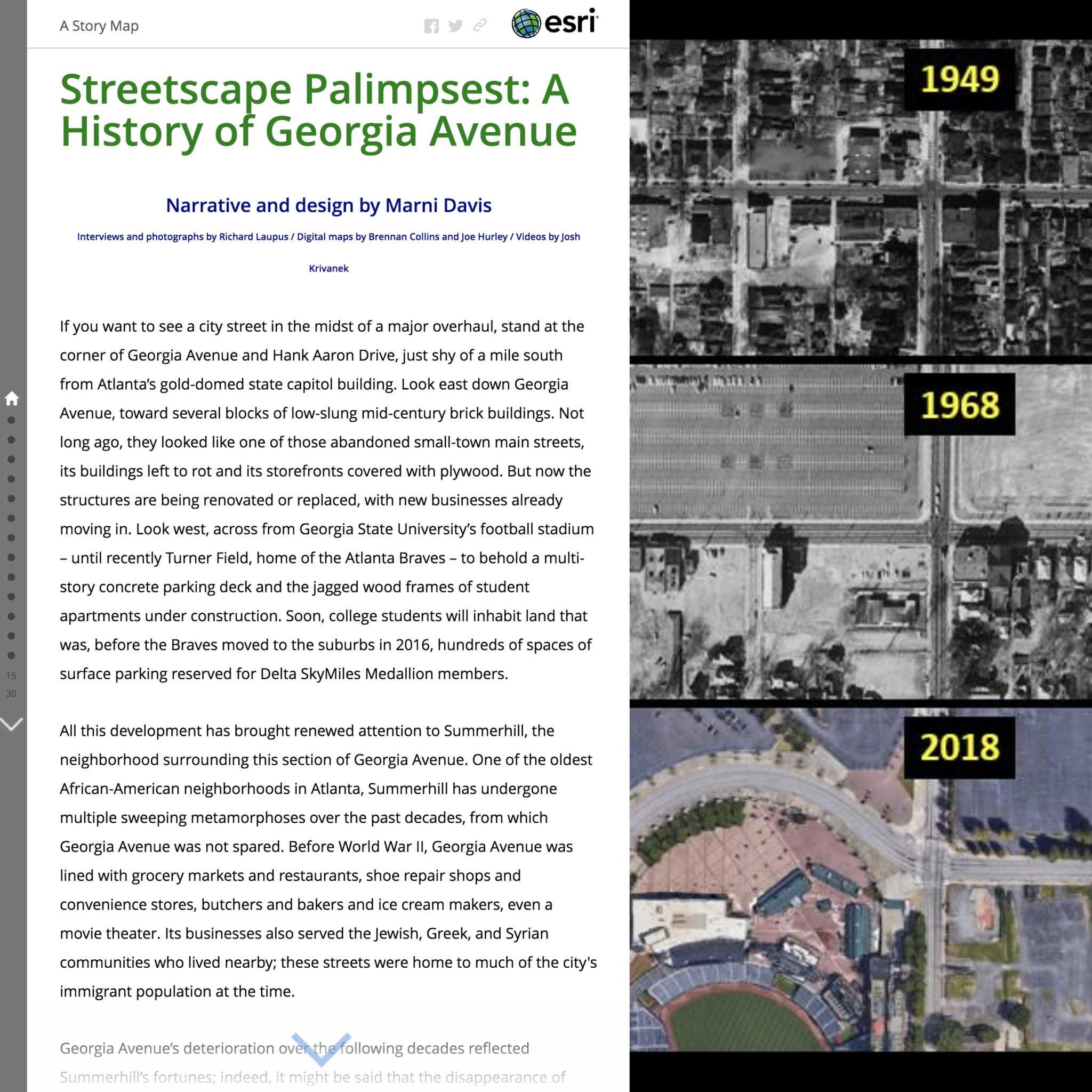

Today, much of Georgia Avenue is cleared of buildings altogether. A section of it cleaves between a massive parking lot, once the site of the old Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium (where the Braves played from 1966 to 1996), and the Georgia State University Football Stadium, which used to be Turner Field (where the Braves played from 1997 to 2016). But before those stadiums were built, the section of Georgia Avenue between Pryor and Martin Streets was a dense and bustling shopping district. Its groceries, butchers, general merchandise stores, and movie theater served the surrounding neighborhoods: Summerhill, which was established by African Americans during Reconstruction; the nearby majority-black neighborhoods of Peoplestown and Mechanicsville; Grant Park, a suburb founded in the 1880s for the white elite and middle class; and a mixed-race area between Capitol Avenue (today Hank Aaron Drive) and Mechanicsville, where Jewish, Greek, and Syrian immigrants had established communities among native-born blacks and whites in the early twentieth century.Georgia Avenue relied on local patronage, and thrived in its dense, mixed-class surroundings.

But when middle class residents departed for the suburbs after World War II, local urban planners and city leaders came to regard the area as a “slum.” By the end of the 1950s, Atlanta’s municipal leadership concluded that dozens of the neighborhood’s blocks, and thousands of its homes, should be demolished as part of the city’s urban renewal efforts. Those blocks were soon replaced by stadiums, parking lots, and highways. Urban renewal devastated all of the surrounding neighborhoods, initiating social, economic, and environmental crises from which they still struggle to recover. And Georgia Avenue, bereft of its once-substantial local base of customers, began its slow and painful demise.

Since the Atlanta Braves left Turner Field for Cobb County, however, the neighborhood has been changing yet again. As affluent Atlantans move back into the city, Summerhill has been among the neighborhoods to gentrify at an astonishing pace. New single-family homes, townhomes, and student housing complexes will soon be ready for occupancy and, as in nearly every other neighborhood in town, the real estate prices have soared. Meanwhile, on Georgia Avenue, what few blocks of old buildings remain are undergoing redevelopment, welcoming upscale retailers that belie the neighborhood’s troubled past. Though many of these new businesses seem to want to capitalize on the street’s historic vibe, the actual history of Georgia Avenue does not lend itself to such easy commodification.

Using Digital Tools to Rediscover Atlanta’s Past

For both myself – a historian at Georgia State University – and my project collaborator, oral historian, photographer, and longtime Summerhill documentarian Rick Laupus, Georgia Avenue’s current breakneck redevelopment was the primary catalyst for creating the “Streetscape Palimpsest” website. To capture these dramatic changes, we created an ArcGIS Storymap that interweaves researched historic narrative with old city maps, archival photos, and videos of interviews with both former and current residents of the surrounding neighborhoods. The platform’s geospatial technology incorporates maps, both historic and contemporary, that users can manipulate to zoom in for detail or pan out for context. Location pinpoints situate both demolished and surviving buildings in space, and even provide information about their former occupants.

These digital and interactive functions root the stories, and the reader, on Georgia Avenue and in its surrounding neighborhoods. In the process, it reveals connections between the street’s past and its present, and enables readers to rediscover a part of their city that has been effectively (though imperfectly) erased.This version of “Streetscape Palimpsest” concludes the first stage of the Georgia Avenue History project, but there’s more to come. This summer, we will curate a physical exhibit based on the website, thanks to a Community Investment Fund grant from the Annie E. Casey Foundation, as well as support from the Atlanta History Center and Carter, Inc., the company that is currently redeveloping Georgia Avenue. Ultimately, we hope that this exhibit will find a home on Georgia Avenue itself, so that local communities, and all Atlantans, can come together in shared space and learn about Georgia Avenue’s multilayered histories.

Citation: Davis, Marni. “Georgia Avenue as Palimpsest: Uncovering the Multilayered Histories of One Street.” Atlanta Studies. May 7, 2019. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20190507.

Notes

- Timothy J. Crimmins, “The Atlanta Palimpsest: Stripping Away the Layers of the Past,” Atlanta Historical Society Journal 26, no. 2–3 (Summer–Fall 1982): 14, http://album.atlantahistorycenter.com/cdm/compoundobject/collection/AHBull/id/24179/rec/6.[↩]