On March 14, Atlanta’s Center for Civic Innovation launched their NPU Initiative, “an independently-led, multi-year study and review of the city’s historic Neighborhood Planning Unit (NPU) system,” a program through which the city government facilitates public participation in planning decisions.

This certainly won’t be the first time that the NPU system has been critiqued or revisited by citizens or the city government since its creation in the 1970s, whether because the process gives either too much or too little power to the citizens it’s supposed to empower.1 However, one important aspect of the NPU system that has remained largely undiscussed since its creation is its geography. But this isn’t because the delineations of the original twenty-four NPUs – as well as the subsequent addition of NPU-Q in the early 2000s – were natural, self-evident ways of subdividing the city. Indeed, as we show in our paper “The Nature of Neighborhoods: Using Big Data to Rethink the Geographies of Atlanta’s Neighborhood Planning Unit System,” recently published in the Annals of the American Association of Geographers, the way Atlanta’s neighborhoods and NPUs are defined was the result of a complex, subjective, and often quite contentious process.2

When the NPU system was first adopted in 1975, some sitting city councilmembers saw the addition of a new kind of supplementary political geography into the city’s planning apparatus – one which, by design, wouldn’t accord with the existing city council district boundaries – as a threat to their political power, especially in the wake of the newly-elected mayoral administration of Maynard Jackson.3 But even once it was decided that citizen participation would be organized around neighborhoods as opposed to city council districts, the city was still left with the task of deciding what exactly constituted a neighborhood, how boundaries would be drawn between neighborhoods, and how constituent neighborhoods would then be aggregated into the system of NPUs. Thus, in Atlanta, the answers to philosophical questions that are more often considered by academics took on a practical character.

What Makes a Neighborhood?

According to the official definition adopted by the city council on April 2, 1975, a neighborhood is “a geographic area either with distinguishing characteristics or boundaries in which the residents have a sense of identity and a commonality of perceived interest, or both” and an NPU as “a geographic area composed of one or more contiguous (connecting) neighborhoods, which have been defined by the Department of Budget and Planning and approved by the City Council for the purpose of developing neighborhood plans.”4 Then-Planning Commissioner Leon Eplan, who had arguably the most formative role in the creation of the NPU system,5 described the process of generating these neighborhood definitions in this way:

. . . the Bureau of Planning prepared a city-wide map showing 177 so-called “neighborhoods“ in Atlanta. These areas were predominantly residential clusters, or sometimes small commercial nodes, with clearly defined boundaries and names. Some were quite large in size, while others were very small . . . With only a limited planning staff for the planning and participation program, and with so many neighborhoods to service, it became necessary to bundle the neighborhoods into larger units. Neighborhoods were placed together when they were physically close and appeared to have similar interests or characteristics . . . Identifying the appropriate name for each neighborhood was deemed essential. Establishing and maintaining neighborhood identity was central to the NPU process, to ensure that residents would identify with their communities and derive a sense of place and pride from living there. 6

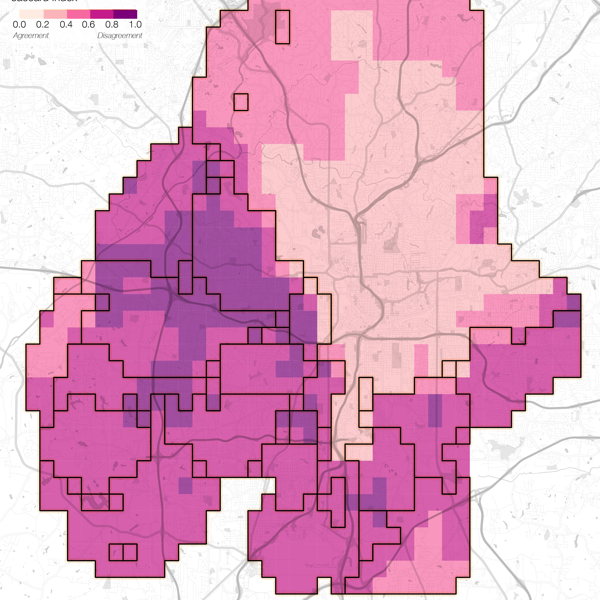

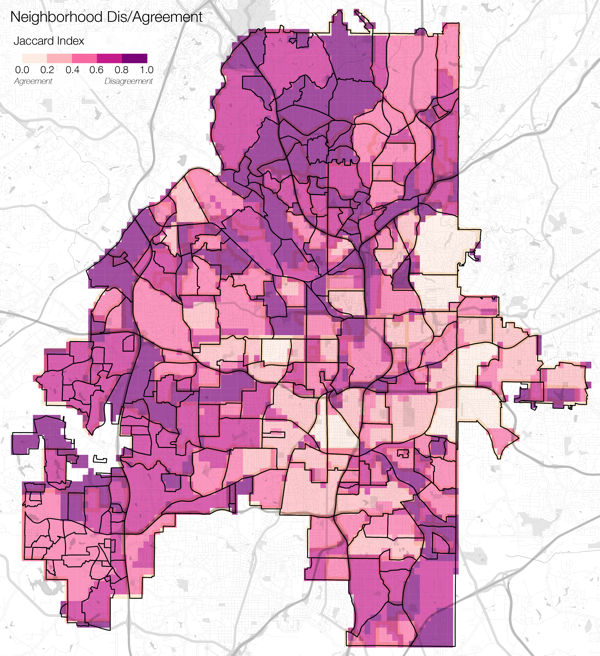

But what constitutes a neighborhood for one person might be different than for their neighbor or a person who lives across town. Indeed, such definitions are also subject to considerable change over time. Whether due to demographic shifts, changes in social networks or social standing, political institutions, or new developments in the built environment, individual and collective perceptions of neighborhood surely evolve over time. Indeed, the city recognized this fact in pair of booklets meant to promote the nascent neighborhood planning system.7In The Value of Neighborhood Planning, the first of these booklets, published in 1973, the city argues that, “Each of Atlanta’s neighborhoods is different from the others, but one element is common to them all. It is change – continuous change.”8 Indeed, our own analysis of archival maps of Atlanta neighborhoods from various planning documents in the 1960s and 1970s revealed that relatively few places within the city were ever represented as belonging to the same neighborhood consistently over time. This is evident in the map to the right, which compares different definitions of the city’s neighborhoods as they were drawn in 1963, 1973 and 1975, with darker purple hues representing those places that saw greater degrees of change or instability in neighborhood definition over time.9

But over the past forty years this reality of constant change has been ignored within the context of the NPU system. As far as we could find, only once, in the early 1990s, did the city undertake an update of its official records of neighborhoods and their boundaries.10 But even those adjustments to neighborhood boundaries were limited to only changing such boundaries within each NPU, in effect ensuring that the stability of the aggregate NPU boundaries wouldn’t be disrupted by such a reassessment.

Re-mapping Atlanta’s Neighborhoods

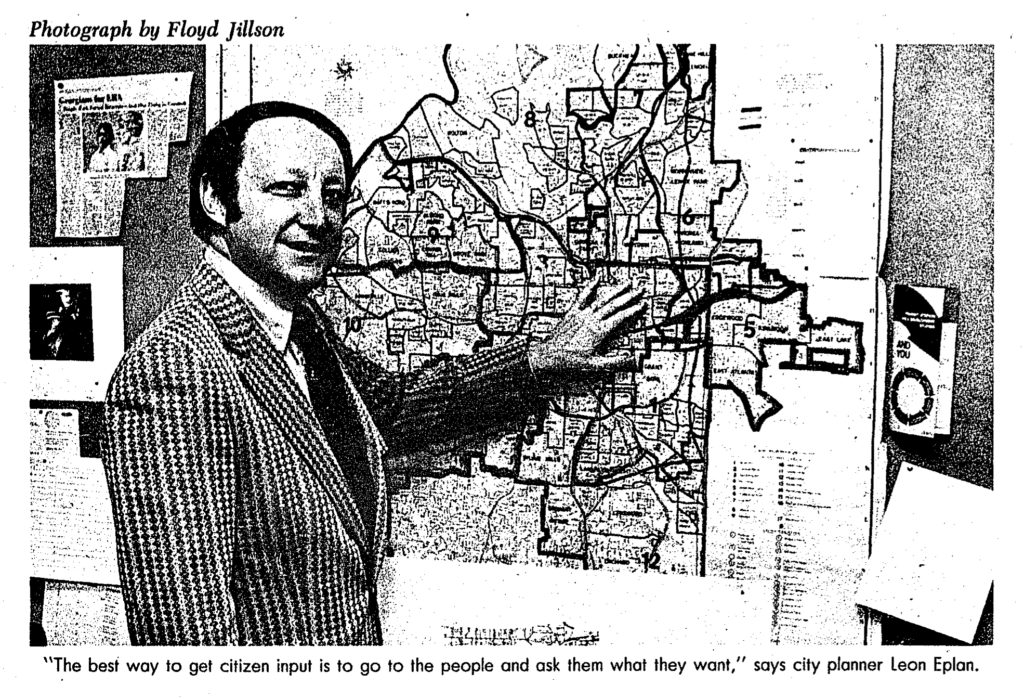

We were interested in what a more contemporary version of the city’s NPUs might look like. But rather than using the more common conception of formal neighborhoods united by a homogeneity in population and/or landscape, we wanted to understand the city’s “functional neighborhoods,” which are defined by people’s everyday movements through and use of urban space. Since this understanding of functional neighborhoods requires data on the mobility patterns of urban residents that aren’t available through more conventional data sources, we turned to the social media platform Twitter, and used an extensive dataset of geotagged tweets in the city of Atlanta as a proxy for those movements. While the use of geotagged social media data for social research comes with a number of limitations – particularly given that social media data provides an unrepresentative sample of the population – such data has proven particularly meaningful as a proxy for the aggregate mobility patterns of large groups of people over relatively long periods of time.11 So not only does the map below provide an alternative, more contemporary view of Atlanta’s neighborhood geographies, but also an understanding of these neighborhoods that emphasizes their relatedness and connectivity rather than their separation, isolation, and distinctiveness.

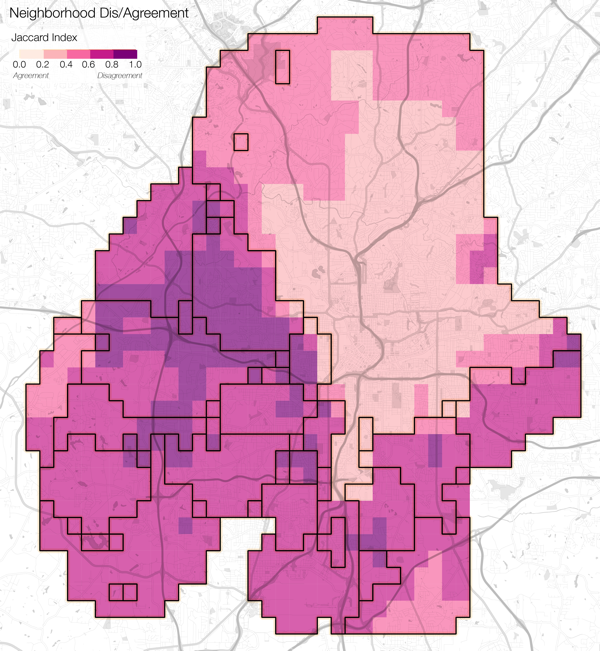

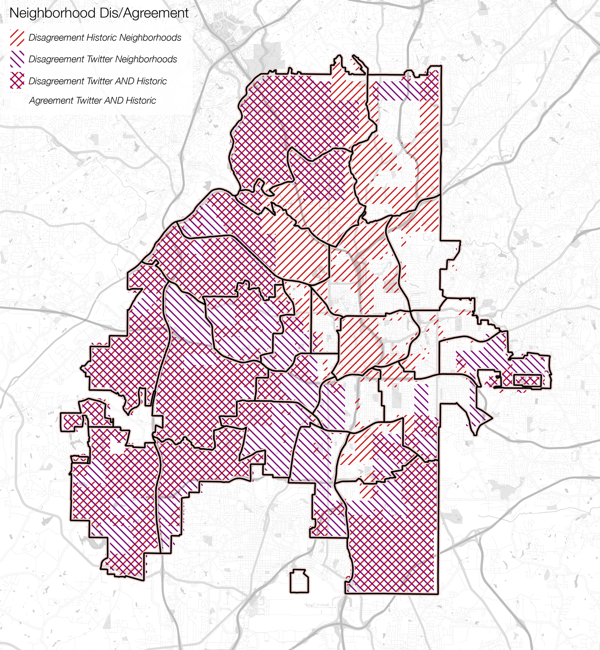

Because there is no one ‘correct’ neighborhood output of this data, the map below represents a composite of several different ways of drawing the city’s neighborhood boundaries based on people’s connections to different places within the city. Like in the map above, the lighter hues represent those places that remain consistently grouped together across multiple outputs, while the darker hues represent places that change groupings much easier. And the black outlines represent one particular neighborhood output that produces twenty-six neighborhoods, which most closely approximates the city’s twenty-five NPUs.

Arguably the most noticeable feature of this map is the size and stability of the one large neighborhood that covers the majority of Atlanta’s northeast area. This area is notable primarily because it largely mirrors Atlanta’s racial geography, in which predominantly white and more affluent residents live to the north and east, while predominantly black and poorer residents live to the south and west. Our more functional and relational analysis of Atlanta’s neighborhoods highlights that in spite of the bevy of different official neighborhoods throughout the city’s northern and eastern reaches, the city’s white residents tend to have one fairly coherent activity space that reaches across the entirety of those areas. Moreover, this one large functional neighborhood deviates so much from the city’s conventional definition of neighborhood boundaries that it includes all of six NPUs, the majority of another five, and at least part of six more. Of the city’s 244 officially-recognized neighborhoods, our northeast neighborhood includes all of eighty-five and parts of an additional forty. In other words, from a functional perspective, many of the formalized neighborhood distinctions in this area are fairly meaningless, as residents are much more expansive in their everyday mobilities through them, though they don’t seem to navigate beyond the confines of this majority white space. At the same time, a considerable portion of the space within this northeast neighborhood cluster has some of the lowest rates of cohesion amongst our different historical neighborhood boundaries. So even though the official definitions of these areas have changed repeatedly, our analysis of functional neighborhoods demonstrates that these places remain functionally integrated with one another in spite of such changes.

While we certainly wouldn’t suggest that the city redraw neighborhoods and NPUs based solely on the locational records of Twitter users, our research does suggest two key things that should be kept in mind as the NPU system is revisited. First, that there’s nothing inherent or natural about the NPU system as it exists today, or even as it was created in the mid-1970s under Maynard Jackson. The NPU system was always the result of political contention and competing visions for how the city would be governed. The question is whether the vision for the NPU system as it’s re-envisioned actually promotes equality and democratic decision-making in the city’s planning process. Second, there is no single set of ‘correct’ neighborhoods that captures the complexity of urban life in Atlanta, nor should any neighborhood map aspire to such simplification. Thus, in rethinking the future of the NPU system, the city and its residents ought to also rethink the way neighborhoods themselves are decided upon and delineated, and how these geographies shape both political power in the city and residents’ understandings of the city and their place within it.

Citation: Shelton, Taylor and Ate Poorthuis. “Rethinking the Geographies of Atlanta’s Neighborhood Planning Units.” Atlanta Studies, August 13, 2019. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20190813.

Notes

- Only a few years after its creation, the NPU program was already under significant attack, both from some of its original detractors, as well as from proponents of the system who felt like it wasn’t living up to its potential. For some examples, see: Lya Martin and Steven A. Holmes, “City NPUs Face Intensive Examination,” Atlanta Constitution, June 9, 1978, C1; Dale Russakoff, “City, Residents Face Off on Poor Process of NPUs,” Atlanta Constitution, June 11, 1978, A19; Maria Saporta, “Neighborhood Planners Will Be Cut to Save Funds,” Atlanta Constitution, October 25, 1982, A10; Robert Anderson, “Many Leaders in NPU See Decline in Effectiveness of the System,” Atlanta Journal and Constitution, June 20, 1985, D1, D4; Ken Foskett, “Letter to the Editor: Neighborhood Planning Units Foster Democracy,” Atlanta Journal and Constitution, April 6, 1992, A8; Thomas Wheatley and Robert Isaf, “Wither the NPU?” Creative Loafing Atlanta, March 26, 2015, http://www.clatl.com/news/article/13082298/wither-the-npu.[↩]

- This research was first presented at the 2016 Atlanta Studies Symposium, held at Georgia State University.[↩]

- Jim Merriner, “District Planning Bid Hit,” Atlanta Constitution, March 17, 1975, D8.[↩]

- It is worth noting that these definitions had been in informal use in earlier planning documents produced by the city.[↩]

- Colin Campbell, “Chief Planner’s Legacy Lies in Neighborhoods,” Atlanta Journal and Constitution, April 4, 1996, B1.[↩]

- Leon S. Eplan, “The Genesis of Citizen Participation in Atlanta,” in Planning Atlanta, Harley Etienne and Barbara Faga, eds. (American Planning Association, 2014), 99.[↩]

- Atlanta Bureau of Planning, The Value of Neighborhood Planning (Atlanta, GA: 1973) and Atlanta Bureau of Planning, How to Do Neighborhood Planning (Atlanta, GA: 1974).[↩]

- The Value of Neighborhood Planning, 5.[↩]

- All maps were collected via Georgia State University’s Planning Atlanta Digital Collection. For more details on our methodology and analysis, see pp. 10–12 (titled “Data and Methodology”) in Shelton and Poorthuis, “The Nature of Neighborhoods.”[↩]

- Michelle Hiskey, “City’s Communities Making the Map,” The Atlanta Journal and Constitution, December 16, 1991, B1; Actor Cordell, “42 More Neighborhoods Recorded in City Since Map of 181 in 1974,” The Atlanta Journal and Constitution, April 9, 1992, E3.[↩]

- For more on how geotagged social media data can be used to understand urban neighborhoods and social inequality, see Taylor Shelton, Ate Poorthuis, and Matthew Zook, “Social Media and the City: Rethinking Urban Socio-Spatial Inequality Using User-Generated Geographic Information,” Landscape and Urban Planning 142 (2015): 198–211, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.02.020.[↩]