In the immediate wake of the passing of Henry Aaron on January 22, 2021, Clif Stratton examines how race shaped Atlanta’s historical efforts to memorialize the accomplishments of the home run king.

In 2013, the Braves shocked the denizens of Atlanta when they announced their pending relocation to Cobb County. After the initial disillusionment waned, questions emerged about who would get what in what some likened to a messy divorce between the baseball franchise and the City of Atlanta. Turner Field was certainly not headed up I-75, destined for what in-town residents derisively refer to as OTP (outside the perimeter). In fact, one of the Braves’ stated reasons for relocating was to manage and profit from the development of the immediate real estate around the new ballpark: restaurants, bars, retail, hotels, corporate offices, and music venues.

The team also defended the move as one of logistical convenience for its fanbase. A ticket sales map released by the team in November 2013 de-centered downtown. As Andy Walter notes, “the map drew lines that reflected enduring divisions (white/black, wealthy/poor) but imbued them with new meaning, distinguishing where the Braves seemed to belong and where they did not.”1 When it came to future economic benefit, the ticket sales data spoke for itself. Yet, the franchise’s historical identity remained pivotal during its contentious relocation to the new epicenter of Braves Country.

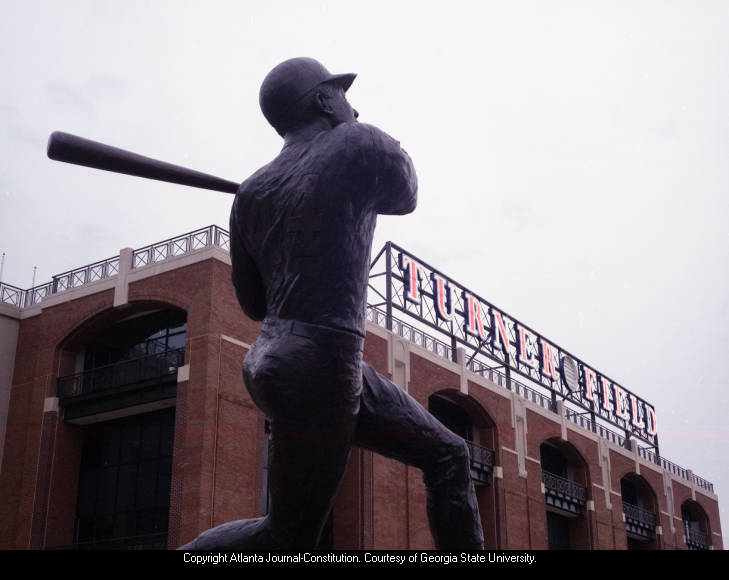

For nearly two decades, Turner Field, which sits about a mile from Five Points, the epicenter of Atlanta’s central business district, had doubled as a museum that presented the Braves’ version of its own storied history. Fans could explore the team’s past, from its lowly beginnings in the shadow of the Boston Red Sox, its move to Milwaukee in 1953, its bold relocation to the former Confederacy in 1966, and the incredible string of fourteen consecutive division titles from 1991-2005.2 This history’s centerpiece was the man whose iconic swing was cast in bronze in 1982 and placed on the concourse outside Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, the same year he was inducted into the baseball Hall of Fame. The statue, which depicted Hammerin’ Hank Aaron crushing record-shattering home run #715, was subsequently relocated across the street in 1997 when the Braves vacated their original digs for Turner Field, the former Olympic stadium that was hastily retrofitted for baseball following the conclusion of the 1996 summer Olympic Games.3

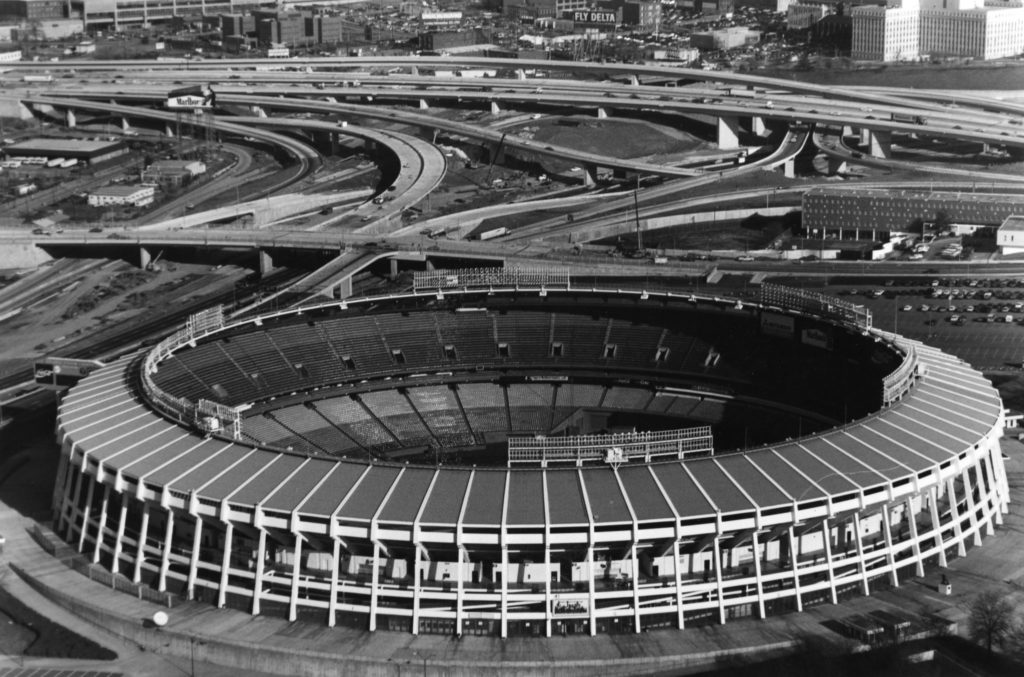

It was at Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium, fondly nicknamed the Launching Pad for the frequency and ease with which the ball seemed to leave the yard, that Aaron hit 190 of his 755 career home runs, second only to Milwaukee County Stadium’s 195, where Aaron played Braves’ home games from 1954-1965 and then again from 1975-1976 as a Brewer.

Atlanta Stadium, as it was known from 1965 until 1974, was the site of Aaron’s 500th (1968), 600th (1971), and 700th (1973) home runs. It was also where he hit the record-breaker on April 8, 1974, the one that sailed over the left field wall and moved Aaron ahead of George Herman Ruth atop the all-time list.

The approximate spot where #715 landed remains memorialized in the Turner Field parking lot, created after the implosion of Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium in August 1997. And it was hard to miss the bronze Hammer towering over the crowds as they gathered outside the ticket windows and gates.

The concourse may have been called Monument Grove, but for his otherworldly accomplishments on the baseball field and his cultural importance, this was a place where Aaron seemed to stand above the others cast in bronze.

For more than thirty years, Aaron’s statue had been a fixture of Atlanta’s baseball landscape, a serene monument to a living legend amidst a sea of concrete, traffic, and foam tomahawks. But before the Braves’ imminent move to Cobb and amidst doubt about Turner Field’s next life, Aaron’s statue served as a flashpoint of contention. Would the statue follow the team or remain in Atlanta?

City or Suburbs?

In February 2016, Atlanta-Fulton County Recreation Authority executive director and future Atlanta mayor Keisha Lance-Bottoms claimed victory, announcing that the city had uncovered “Olympic-era documents” proving that the Aaron statue belonged to the city via the Stadium Authority. The Braves promptly cried foul, claiming that only Henry Aaron, who serves as Braves senior vice president, should decide the statue’s fate.

Aaron, ever wary of weighing in on the material manifestations of his legacy, expressed ambivalence even before the struggle between the team and city became public: “On one hand, I think the statue should be wherever the baseball park is, where the Braves are playing,” Aaron said. But given that the statue was not paid for by the team but instead through fan contributions, “if you had to think about it, it all belongs to Atlanta, to the people of Atlanta.”4 Surely this conflict of interest would not sit well with the intown faithful, already up in arms about the team’s departure. Aaron was an Atlanta treasure, and Cobb County was decidedly not Atlanta in the minds of many.

But resolution ensued quickly. Rather than quarrel with the city, the Braves would simply commission a new statue for SunTrust Park. The original would remain within the city limits, either at a repurposed Turner Field or potentially at the Center for Civil and Human Rights, located on Ivan Allen Jr. Boulevard, the street named for the Atlanta mayor credited with bringing the Braves to Atlanta in 1966. “No matter where they choose, we have won because we can honor Hank Aaron’s Atlanta legacy,” remarked local journalist Maria Saporta.5

The few writers who covered the statue controversy did not note it at the time, but the struggle over the statue’s ultimate destination – city or suburbs – exposed the broader historical currents of metropolitan Atlanta that, at their core, have always been about race.

During the tumultuous 1950s and 1960s, Cobb County was a preferred destination for white residents hellbent on escaping integration. It served as both a real and symbolic reminder that Atlanta was not exactly “the city too busy to hate,” as former mayor William B. Hartsfield famously remarked. And though Cobb County has become more racially diverse in the twenty-first century (the black population grew by 47% from 2000 to 2010), its majority-white population has repeatedly opposed the extension of MARTA, Atlanta’s public transportation network, in part because of the socioeconomic and demographic changes (read: race and class) that increased accessibility might produce.6

But now Cobb had the Braves. And at least for a time, they seemed to want Aaron’s statue, too.

An Icon for the ‘City Too Busy to Hate’

Arguably the city’s second most recognizable cultural icon aside from Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Henry Aaron was and is many things to many people: reserved ambassador, car dealership owner, stoic mentor, genuine human being, rightful home run king: #755isreal. But principal among them is his role in a story that Atlanta likes to tell itself about race.

Aaron’s arrival in 1966 offered Atlanta’s liberal establishment, both white and black, the chance to demonstrate the city’s racially progressive credentials to the rest of the nation. As the Braves prepared to move from Milwaukee ahead of the 1966 season, Mayor Allen assured the team’s star that the indignities of segregation that still plagued some ballparks would not define the experience at Atlanta Stadium. Likewise, Leroy Johnson, Georgia’s first black state senator since Reconstruction, attempted to disarm the slugger of any fears concerning segregation and racism. Johnson reminded Aaron that Atlanta Stadium would be but one of many public and private integrated facilities in the city. While he acknowledged all American cities had room for improvement, Johnson also toed the establishment line: “The business community, the city administration as well as Negroe [sic] and White leadership have joined forces to keep Atlanta moving forward.”7

Beginning in 1972, when it became abundantly clear that, barring a career-ending injury, Aaron would eventually break Ruth’s record, racist mail flooded the Braves’ front office. In response, Atlanta’s movers and shakers clamored to celebrate Aaron’s pending immortalization, rather than bemoan the inevitability of a former Negro Leagues player toppling the most coveted record in American sports – one that was set when black players were prevented from donning a major league uniform.

Upon retirement from baseball as a Milwaukee Brewer, Aaron returned to the Braves, where new team owner Ted Turner gleefully promised the Hammer a job for life. The prodigal son had returned to the team he had made famous and to the city that so needed to feel good about itself at a time of deep-seated racial animosity.

But it wasn’t to be. In the early 1980s, the campaign to commission the original Hank Aaron statue served as a critical flashpoint in Atlanta’s history, one that foretold the more recent battles over the place of Aaron and the Braves in the city’s cultural and spatial landscape.

Jim Crow Origins

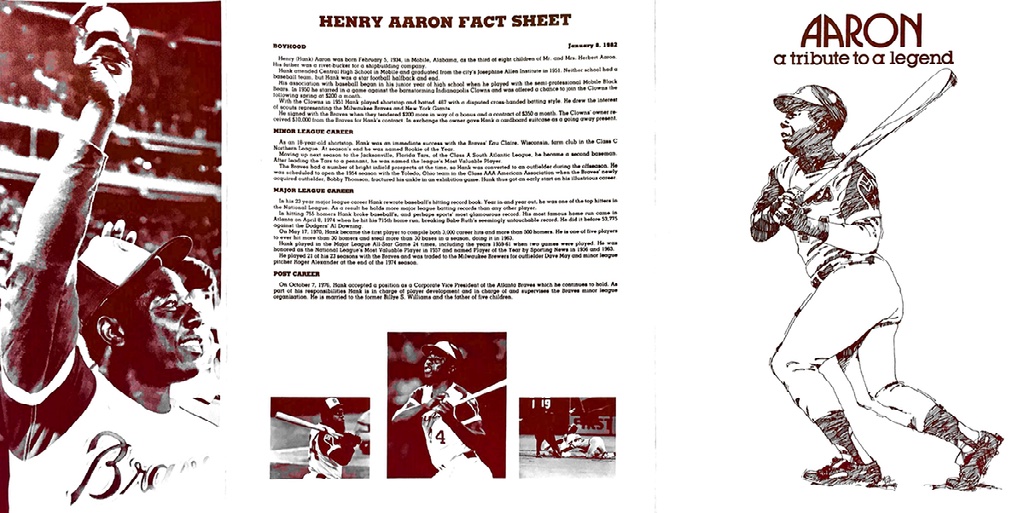

Henry Louis Aaron was born in 1934 in Mobile, Alabama. Though it lacked the reputation of Birmingham’s abhorrent racist violence, Mobile still typified Alabama’s Jim Crow norms. When the Aarons moved further out to Toulminville so that his father Herbert could realize his dream of building and owning his own home, they distanced themselves from what little integration there was in city center. In Toulminville, Henry honed his craft as a batsman, clipping bottle caps with a stick when he wasn’t playing in organized games sponsored by local companies.

Aaron began his professional baseball career in the waning days of the Negro Leagues as an outfielder for the Indianapolis Clowns. But only fourteen games into his career, the Boston Braves purchased his contract and shipped him off to their farm team in Eau Claire, Wisconsin. Little did unsuspecting Boston fans know that the Major League club would soon relocate to the Badger state too. Aaron’s stint with the Eau Claire Bears lasted the remainder of the 1952 season. He hit .336, made the all-star team, and was named league MVP. Next year, Aaron was promoted to class-A Jacksonville (Florida). The South Atlantic League, colloquially called the Sally, truly tested the limits of professional baseball’s commitment to integration. By the time Jackie Robinson had completed his sixth year with the Brooklyn Dodgers, Aaron was part of a handful of black players, including his teammate Felix Mantilla, who integrated the Sally in 1953. “Jacksonville wasn’t so bad,” Mantilla recalled. “But places like Columbus and Macon, those places were wicked.” Prior to the arrival of Major League baseball in Atlanta, the southern leagues and the Florida spring training homes of the big-league clubs (the Milwaukee Braves held camp in segregated Bradenton) served as proving grounds for how white fans would respond to the changing racial composition of their beloved teams.8

It was not easy. Aaron, Mantilla, and other black ballplayers not only had to cope with standard segregationist practices when it came to accommodations, transportation, and dining. They also navigated clubhouses, carefully anticipating how their white teammates might react to or sometimes participate in the daily humiliations directed at the league’s few black players. Their lockers were often clustered in neglected corners, and to enter some ballparks, black players had to use separate gates.

It was a set of experiences that furthered Aaron’s proclivity to remain aloof from the sports media and from his own teammates, save for a few close friendships. He held strong convictions regarding the inherent equality and dignity of black people. And he remained in awe of Jackie Robinson’s fortitude in the face of the vilest racism white baseball fans (and some players) could muster in the late 1940s. But most instead chose to see Aaron as a simpleton ballplayer who possessed magical wrists, hit for both average and power, and thought little about the wider world around him. They were wrong, of course. But Aaron’s understandable guardedness did not help matters.9

By the time of his retirement, Aaron had won the National League MVP award and a World Series title (both in 1957) with the Milwaukee Braves, the two most coveted individual and team accolades in professional baseball. But it was his consistency over twenty-two seasons that had the baseball world marveling: most RBI (2,297), most games played (3,298), most plate appearances (13,940), and most home runs (755).

On the run up to breaking the home run record, Aaron’s celebrity and cultural significance increased exponentially. He began to transcend the already much-admired athletic prowess that drew sportswriters and fans to him since the 1950s, capturing the imagination of Americans unsure of what the post-Civil Rights era might hold. To his supporters, Aaron became a highly visible symbol of the progress of African Americans. But even in retirement, with a first ballot Hall of Fame vote a lock, Aaron could not escape the ways in which his fame left white and black Atlantans struggling over how the city should immortalize him.

Shut Up and Play

Controversy ensued in January 1980 when Georgia-born humorist Lewis Grizzard, whose public career frequently embodied the white reactionism of the post-Civil Rights Sunbelt South, lambasted Aaron in his regular Constitution column. Aaron had recently refused the annual Sporting News award presented by baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn, of whom Aaron had been openly critical for his deafening silence on the racism that seethed below the surface of America’s pastime.

You also did your ‘baseball is racist’ number again . . . Not enough black ex-ballplayers in baseball front offices, you say. Not enough commercials and other easy money for black ex-ballplayers, you say . . . Frankly, Henry, why don’t you cool it?”10

Grizzard continued:

You’ve made a ton of money, and you do TV shows, and even Kentucky Fried Chicken wants you. And you have a terrific job because you really don’t have anything to do.11

Grizzard closed with,

You could give us another great moment, Henry – a moment of silence. In other words, zip your lip and get around to something worthwhile, like finding a way to remove Atlanta’s miserable excuse for a baseball team from last place.12

In other words: “shut up and play” – a phrase frequently uttered in various iterations at professional athletes – retired or otherwise – who dare to challenge inequity.

Grizzard followed up a few weeks later with excerpts from the letters he’d received in response to the column. They revealed the divisiveness of race: “Your article on Henry Aaron was overdue,“ wrote one reader. “His most recent egocentricity is deplorable.” Conversely, another reader scolded Grizzard: “It is interesting to see when a black man stands up and speaks his mind, he is all of a sudden a ‘bad boy’ …. Keep your personal opinions to yourself.”13

The NAACP swiftly came to Aaron’s defense. The Atlanta branch “wholeheartedly” supported Aaron’s right to refuse the award from Kuhn and to “call attention to racism and injustice in the field of baseball.” Julian Bond, author of the NAACP’s scathing letter to Hal Gulliver, editor of the Constitution, called Lewis Grizzard’s recent attack on Aaron “repulsive to any fair-minded person…vitriolic and racist…clearly demeaning and degrading to all black people.” Bond demanded a public apology from Grizzard.14 None materialized.

Grizzard’s column presaged the ensuing struggle among local boosters and organizations over how to honor the home run champion’s legacy as he approached Cooperstown.

Casting the Hammer

In an updated press release, likely released some time in 1981, the Atlanta Branch of the NAACP lamented the fact that there is “no indication that the Atlanta Stadium Authority plans to honor [Hank Aaron] in an appropriate manner.”

The branch called on the Stadium Authority to erect a statue “in a strategic place where every visitor to the stadium can see it . . . Understand that we respect the accomplishments of Ty Cobb, but we find it difficult to rationalize that a statue of him has been erected at the stadium while he played no role in its development or its enhancement.” While the NAACP did not state it directly, Cobb’s reputation as a white supremacist also served as an immediate disqualifier for immortalization at the stadium. Aaron, on the other hand, “has caused this area, as well as the stadium to gain in prestige,” the branch noted.15

Perhaps in an attempt to fill the void created by the Stadium Authority, local admirers of the home run champion formed the Committee to Honor Hank Aaron. The non-profit’s sole purpose was to raise $100,000 dollars during the summer of 1981 for a 4000-pound, 16-foot-tall bronze statue of Aaron to be placed on the stadium concourse. Atop a six-foot base, Aaron would be cast in his classic swing pose. A small memorabilia room complete with some of Aaron’s “most treasured keepsakes” would be open to fans on game days. “Go to bat for a legend,” the ad card read.16

The committee was a curious one, comprised not of a multi-racial coalition of prominent Atlantans. It was an all-white, all-male committee. But not if you asked the central organizers. A lengthy list of honorary chairpersons included pugilists Muhammad Ali and Sugar Ray Leonard, boxing promotor Don King; record producer Barry Gordy; comedians Richard Pryor, Dick Gregory, Flip Wilson, and Bill Cosby; actors Lena Horne, Diana Ross, and Sidney Portier; and athletes Althea Gibson, Bill Russell, O.J. Simpson, and Reggie Jackson. This who’s who of black culture and entertainment offered the kind of legitimacy sought by the organizing committee, which they could not muster from themselves or from the other honorary chairpersons, including former, current, and future presidents Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, and George Bush; Georgia Governor George Busbee; University of Alabama football coach Bear Bryant and former Alabama quarterback Joe Namath. Perhaps only the inclusion of George Wallace or Lester Maddox would have provided a starker contrast to the cultural weight of the honorary black chairpersons.17

“A $100,000 statue is already a certainty for Hank Aaron,” proclaimed Atlanta Journal staff writer Norman Arey. Likely to ensure that Milwaukee did not outdo Atlanta in its efforts to honor the home run champion, state senator and executive director of the Stadium Authority, Leroy Johnson, the same person that assured Aaron of Atlanta’s racially progressive attitudes in 1966, said he planned to recommend that Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium be renamed in honor of Aaron.18

The Committee to Honor Henry Aaron was confident in their ability to raise the $100,000 in the summer of 1981 alone. But the ’81 season came and went, and as spring training approached in early 1982, fundraising had floundered. The statue would ultimately require the organizing prowess of the Atlanta NAACP.

Tribute to a Legend

Following Aaron’s election to the Baseball Hall of Fame in early 1982, the Atlanta NAACP assumed the responsibility for planning the city’s celebration of the Hammer. In February, as Black History Month drew to a close, the Atlanta branch called on black Atlantans to honor a man who “has ‘paid his dues’ in the civil rights arena, as well as on the baseball diamond. We must not allow his achievements to go unheralded by his own people.”19

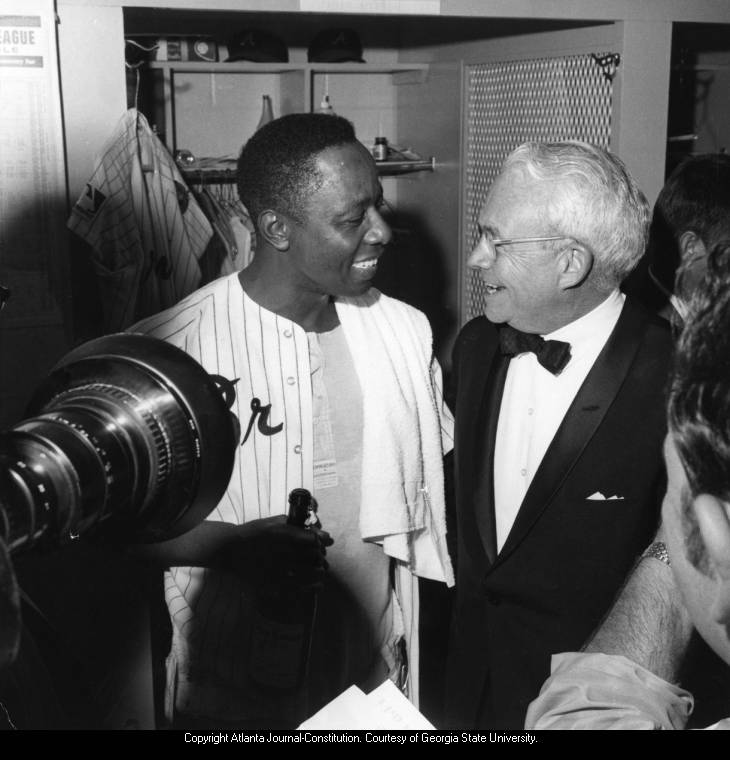

The Salute to Hank Aaron banquet was to be the city’s tribute to a living baseball legend, a player who’d emerged from the Negro Leagues and over the course of his major league career, had amassed more home runs than Ruth. “A tremendous year in the life of Hank Aaron,” commissioner Kuhn remarked: “It is all so richly deserved because of what he has meant to baseball and to the NAACP all these years.”

Atlanta NAACP volunteers sold tickets, handled promotion, and organized the evening’s logistics, including guest speakers and presentations to honor Aaron. The Constitution quoted Aaron as announcing that: “the main thing I’m concerned about now is helping people off the field – people who have been deprived. I hope this [banquet] will be a sellout.”20

As the event approached, Ronald Reagan wrote Aaron from the White House, congratulating him on “[capturing] the imagination of the entire nation,” on the “enjoyment and inspiration” he brought to “youngsters and sports fans,” and on the “uplifting example” he set. The president described Aaron as an athlete that passed through a “crucible of progress” and emerged as a “gentleman and a leader of his people.”21 The Atlanta NAACP urged local pastors to prepare to solicit “a special offering” from their congregations on Sunday, April 18th, the day following the banquet.22

On April 17, 1982, the NAACP held the Salute to Hank Aaron banquet at the futuristic Hyatt Regency House, an 800-room hotel built in 1967 by private architect-turned-developer John Portman.

Though fifteen years old by the time of the banquet, the Hyatt Regency remained the architectural crown jewel of the central business district. To an automobile traveler moving south on Atlanta’s downtown expressway, the Hyatt’s shiny blue glass dome marked the northern edge of the Peachtree Center complex, Portman’s sprawling “city within a city.” Peachtree Center became the preeminent model for private urban renewal in 1960s and 1970s, catering to the tastes and sensibilities of the professional and managerial classes, tourists, conventioneers, and suburbanites. And it insulated both its infrequent visitors and regular occupants from the perceived ills of downtown Atlanta: congestion, crime, and poverty.

And race was always there in background: an unspoken code obscured by otherwise legitimate concerns about one’s experience and safety in the city. Portman’s critics charged him with using “fortress architecture” to insulate white-collar professionals from the visceral realities of Atlanta’s black poor. As Henry Aaron devoted his post-baseball life to uplifting the downtrodden who had been marred by decades of racist policy, the banquet’s Hyatt location symbolically cut against these efforts. Nonetheless, Portman’s name was listed on the local organizing committee.23

The evening’s program featured some local heavy hitters. Rubye Lucas – wife of the late Bill Lucas, Aaron’s former teammate and the first black Major League general manager (of the Braves) – offered introductions with Herman J. Russell, Atlanta’s most prominent black real estate developer. Commissioner Kuhn, Jet magazine editor Robert Johnson, Rachel Robinson (widow of Jackie Robinson), and former Atlanta mayor Ivan Allen Jr. all offered opening remarks.

Two-minute presentations from Martin Luther King III, Atlanta Mayor Andy Young, Georgia Governor George Busbee, Fulton County Commission chair Michael Lomax, and a special representative sent by President Reagan preceded the premiere showing of “A Tribute to a Legend.” The NAACP’s Julian Bond followed with a special presentation. Jesse Hill Jr. introduced Aaron. Ed Dwight unveiled the bronze statue of the Hammer to be placed on the concourse outside Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium later that summer.24

By all accounts, the evening really did showcase Atlanta as Hartsfield had described it: the “city too busy to hate.” But not for long.

Alleged Impropriety

Following the Salute to Hank Aaron Banquet, the Atlanta NAACP was soon embroiled in a financial scandal over the banquet proceeds. On July 1, Gary Bross, attorney for and director of the Committee to Honor Hank Aaron inquired about funds raised. Bross estimated that 880 people attended the dinner, grossing $88,000 “for the meal alone.” Yet he could only account for approximately $60,000 in proceeds.

The Committee directors were also “troubled” by the $6,280 “taken out as a membership fee to the NAACP.” “I could find no authority or representation that the tribute would involve membership in your organization,” Bross puzzled. He asked branch director Jondelle Johnson for a complete breakdown of expenses upon the assumption that everything about the evening was donated except the dinner itself. Bross also requested “a breakdown of contributors, rather than the list of donors who made contributions.” He suspected that many corporate contributions were “intended to benefit the statue” and was “curious to find out where these sums went inasmuch as no meals were served to them.”25

Julian Bond refuted claims that the Atlanta Branch had not given “a fair share” of the banquet proceeds to the all-white Committee to Honor Hank Aaron. Bond asserted that the banquet was as much to raise funding for the Hank Aaron statue as it was for NAACP causes. The state senator critiqued the underwhelming ability of the Committee to raise money, purportedly its raison d’être:

We are proud to have raised more money to erect a statue to Hank Aaron at Atlanta Fulton County Stadium in one night than the Committee organized for that sole purpose had been able to raise in two years.26

Bond called on committee president and Atlanta public relations executive Bob Hope to publicly repudiate the allegations. “The NAACP sold the tickets and the ads, arranged for the presentations made at the dinner, did all the work and bore every expense of mounting a successful evening.” The Committee had received more than half of the banquet’s proceeds after having done far less than half of the organizational work. As Bond wondered,

We are frankly unable to explain why they feel they are entitled to more than half of the proceeds after having contributed so little to the evening, and are so ungrateful for our efforts in doubling the money for the statue.27

As of May 13, 1982, the Committee to Honor Hank Aaron had only raised $16,000 save the money from the banquet.

Hope ultimately apologized, citing a ‘non-controversy’ created by a few committee members who scoffed at what they considered a rather meager NAACP gift furnished for the statue.28 But the local press ran with it. Sportswriter Jeff Denberg laid blame at the feet of the NAACP, claiming that when comedian Flip Wilson committed $5,000 to the statue fund, he foolishly cut his check to the NAACP, which promptly deposited it in their general fund. In contrast, Atlantan Charles Ackerman made his check for $5,000 to the Committee to Honor Hank Aaron. “How embarrassing,” Denberg remarked, suggesting that the NAACP had been less than forthright about the destination of donations received.29

“Aaron Fund, NAACP at Odds,” the Jane Hansen headline announced on July 16, 1982. The Journal-Constitution writer implied that the Committee to Honor Hank Aaron was $19,000 short of its now $125,000 goal “partly because it has received only about half of the money expected from a spring fundraiser with the NAACP,” and that Committee members “believe the NAACP might have pocketed more than its share.”

Isabel Gates Webster, a lawyer for and member of the Atlanta NAACP, called the article “libelous,” having “exposed us to public hatred, contempt, and ridicule.” Calls from members and the “community at large” had already poured into the branch office. Webster requested a retraction from AJC president David Easterly “in as conspicuous and public a manner as the article and headline previously published.”30

Perhaps it was Bennie Boyd of Decatur, an active NAACP member, who truly clarified the racial power structures at work in the statue controversy. In a letter to the Atlanta Daily World editor, Boyd questioned

how staff writers from Tucker and Sandy Springs {both largely white suburbs} can so easily make the NAACP the heavy for the poor showing of the committee set up to raise funds. The NAACP is not now and never has been an agency set up to build statues of affluent ball players to be displayed in front of municipal stadiums making millions of dollars for white millionaires. All 755 of those home runs were hit for white owned teams in front of predominately white crowds. 31

Citing his recent attendance at the NAACP’s national conference in Boston, Boyd assured readers that NAACP funds were, now more than ever, needed to combat discrimination, promote jobs, and do the general work of the Black Freedom movement. Statues were tangential to this mission at best, even if Aaron was the most famous living (adopted) black Atlantan. “Love and respect for Hank,” Boyd concluded, was what prompted the Atlanta branch to do the work of honoring Aaron. That whites in the press and local politics would then suggest financial impropriety was beyond the pale.32

Salve for a City

The Salute to Hank Aaron banquet ultimately put the statue fund near enough to the original goal. The bronze hammer’s unveiling on September 7, 1982, tardy for Aaron’s August 1 Cooperstown induction, seemed to put to rest the conflict between the NAACP and the defunct Committee to Honor Hank Aaron. It came fortuitously near the end of a rare competitive season for the 1980s Braves, who won the division that year with MVP Dale Murphy at the helm.

As Aaron approaches his 40th anniversary as a Hall of Famer, Atlantans navigate an everchanging metropolis. Long assumed political realities are influx as statewide conservative dominance frays at the increasingly younger, diverse, and educated suburban edges of Atlanta. In the wake of George Floyd’s murder in May 2020, local racial justice activists revived Atlanta’s own storied history of rebellion against police and vigilante violence. For its part, the Braves franchise leveraged Aaron’s legacy in its solidarity statement on social media: “As a team that moved into the heart of the Civil Rights movement in 1966, we saw firsthand our legend endure discrimination and racism as he chased the home run record. Enough!”33 Whether the team will seriously commit to this work remains an open question.

Even after his passing in January of 2021, the memory of Henry Aaron, ever Atlanta’s dignified ambassador, remains a salve for a city whose racial wounds continue to fester long after the onset of white flight and the tumult of urban rebellion. The Braves arrived in Atlanta amidst convulsive change. The urban core lost 160,000 residents over the course of the 1960s and 1970s. From then on, many fans who attended games had only fleeting connections to the city that hosted their beloved team. The freeways called them home after the final pitch. When the Braves departed for Cobb, the ties that once bound suburban fans to the location of Aaron’s historic accomplishments finally severed. The bronze hammer now stands as one of a handful of visible reminders of an earlier iteration of Braves Country.

Cover Image Attribution: Hank Aaron’s statue after installation at Turner Field, 1997. AJCNL1997-03-19-01a, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library. Courtesy of Georgia State University.

Citation: Stratton, Clif. “Bronze Hammer: Race and the Politics of Commemorating Henry Louis Aaron.” Atlanta Studies. February 2, 2021. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20210202.

Clif Stratton is Associate Professor of History at Washington State University. A 2010 recipient of a Ph.D. from Georgia State University and born and raised in Atlanta, Stratton is the author of Power Politics: Carbon Energy in Historical Perspective (Oxford, 2020) and Education for Empire: American Schools, Race, and the Paths of Good Citizenship (California, 2016). Email him at clif.stratton@wsu.edu.

Notes

- Andy Walter, “Mapping Braves Country,” Atlanta Studies, November 2, 2015, https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20150909.[↩]

- In no subtle reference to Atlanta’s place in Confederate lore, on opening night the stadium scoreboard read: “April 12, 1861: First Shots Fired on Fort Sumter . . . April 12, 1966: The South Rises Again.”[↩]

- On Olympic-era Atlanta, see Charles Rutheiser, Imagineering Atlanta: The Politics of Place in the City of Dreams (London: Verso, 1996); Maurice Hobson, The Legend of the Black Mecca: Politics and Class in the Making of Modern Atlanta (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 169-248.[↩]

- “Where will Hank Aaron’s statue end up when Braves move to new stadium?” Fox Sports, February 10, 2016, https://www.foxsports.com/stories/mlb/where-will-hank-aarons-statue-end-up-when-braves-move-to-new-stadium; “Braves ‘surprised’ at Hank Aaron statue report,” USA Today, February 10, 2016; Kevin Reichard, “Will Henry Aaron statue make move to suburbs?” Ballpark Digest, February 12, 2015, https://ballparkdigest.com/2015/02/12/will-henry-aaron-statue-make-move-to-suburbs/.[↩]

- Terence Moore, “Latest statue hammers home Aaron’s legacy,” mlb.com, March 29, 2017, https://www.mlb.com/braves/news/braves-unveil-hank-aaron-statue-at-suntrust-c221511284; Maria Saporta, “Commentary: Atlanta wins dispute over Hank Aaron statue,” Saporta Report, September 1, 2016, https://www.wabe.org/commentary-atlanta-wins-dispute-over-hank-aaron-statue/.[↩]

- See Kevin Kruse, White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005); Jacob Anbinder, “The South Will Ride Again: The Making of MARTA and the Origins of the Urban South,” Yale Historical Review 2, no. 3 (Spring 2013), 37-57; Kruse, “What does a traffic jam in Atlanta have to do with segregation? Quite a lot.” New York Times Magazine, August 14, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/traffic-atlanta-segregation.html.[↩]

- Leroy Johnson to Henry Aaron, October 24, 1964, City of Atlanta Records, Series XV, Box 17, Folder 7, Kenan Research Center, Atlanta, History Center.[↩]

- Quoted in Howard Bryant, The Last Hero: A Life of Henry Aaron (New York: Anchor, 2011), 54.[↩]

- Aaron’s life is magisterially told in Bryant, The Last Hero. Also see, Hank Aaron with Lonnie Wheeler, I Had a Hammer: The Hank Aaron Story (New York: Harper/Perennial, 2007).[↩]

- Lewis Grizzard, “What Made ‘Hammer’ Into ‘Bad Henry?'” Atlanta Constitution, January 31, 1980. On Lewis Grizzard, see James C. Cobb “Lewis Grizzard (1946-1994),” New Georgia Encyclopedia, August 22, 2013, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/arts-culture/lewis-grizzard-1946-1994; Peter Applebome, Dixie Rising: How the South is Changing American Values, Politics, and Culture (New York: Times Books, 1996), 327-339.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- Lewis Grizzard, “The Hammer’s Fans and Foes Get Their Say,” Atlanta Constitution, February 18, 1980.[↩]

- Bond to Gulliver, February 28, 1980, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Atlanta Branch Records (hereafter NAACPABR), aarl98-007, box 20, folder 7, Auburn Avenue Research Library (hereafter AARL).[↩]

- Press Release Re: Hank Aaron, NAACPABR, box 28, folder 6, AARL. When the Aaron statue controversy ensued in 2016, the Braves had no interest in taking Ty Cobb’s statue with them to SunTrust Park. One journalist has recently challenged Cobb’s popular image as a virulent racist. See Bill Torpy, “Everybody Wants the Hammer, Nobody Wants the Peach,” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, February 18, 2016, https://www.ajc.com/news/local/torpy-large-everybody-wants-the-hammer-nobody-wants-the-peach/7ChUqy4qLJjekXzx6DdY9O/.[↩]

- Statement announcing the Committee to Honor Hank Aaron, Inc., NAACPABR, box 29, folder 1, AARL.[↩]

- List of Honorary Chairmen, Committee to Honor Hank Aaron, NAACPABR, box 28, folder 5, AARL.[↩]

- Atlanta Journal, undated clipping from 1981, NAACPABR, box 28, folder 5, AARL.[↩]

- “The Black Letter,” undated, NAACPABR, box 29, folder 1, AARL.[↩]

- Atlanta Constitution, February 10, 1982, clipping, NAACPABR, Box 6; NAACP News Bulletin, February 9, 1982, NAACPABR, box 28, folder 5, AARL.[↩]

- Reagan to Aaron, April 6, 1982, NAACPABR, box 28, folder 6, AARL.[↩]

- King, Oldham, and Blackshear to Pastors, A Tribute to a Legend Letter, March 31, 1982, NAACPABR, box 28, folder 5, AARL.[↩]

- Irene Holliman Way, “’Creating a City Within a City’: John Portman’s Peachtree Center and Private Urban Renewal in Atlanta,” Atlanta Studies, January 15, 2019, https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20190115; Local Committee List, NAACPABR, box 28, folder 5, AARL.[↩]

- Program, Salute to Hank Aaron, April 17, 1982, NAACPABR, box 28, folder 6, AARL.[↩]

- Bross to Johnson, July 1, 1982, NAACPABR, box 28, folder 5, AARL.[↩]

- “NAACP Was Fair to Hank Aaron, Says Bond,” Statement by Julian Bond, July 16, 1982, NAACPABR, box 29, folder 1, AARL.[↩]

- Ibid.[↩]

- Hope to Bond, July 23, 1982, NAACPABR, box 28, folder 7; Hope to Bond, May 23, 1982, NAACPABR, box 28, folder 5, AARL.[↩]

- Jeff Denberg, “Atlanta dishonors home run king,” undated press clipping, NAACPABR, box 28, folder 5, AARL.[↩]

- Webster to Easterly, July 23, 1982, NAACPABR, box 28, folder 5, AARL.[↩]

- Atlanta Daily World, August 3, 1982, clipping, NAACPABR, box 28, folder 7, AARL[↩]

- Atlanta Daily World, August 3, 1982, clipping, NAACPABR, box 28, folder 7, AARL.[↩]

- Braves, “Enough!” June 2, 2020, accessed December 10, 2020, https://www.instagram.com/p/CA8Wy2Bs6Db/?igshid=pjalib1xpeeu.[↩]